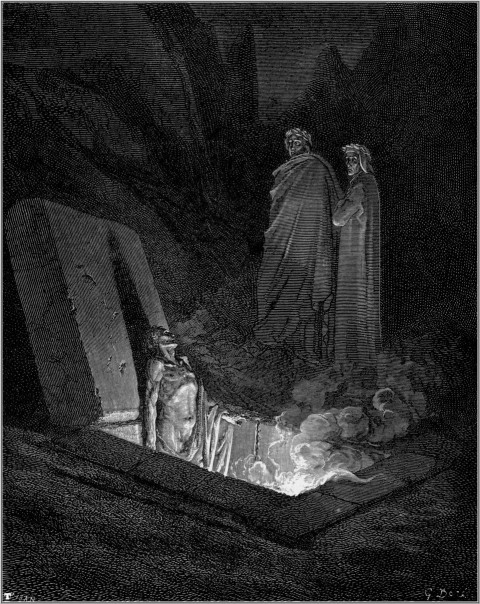

Inferno, Canto X:

Many artists have attempted to illustrate Dante Alighieri’s epic poem the Divine Comedy, but none have made such an indelible stamp on our collective imagination as the Frenchman Gustave Doré.

Doré was 23 years old in 1855, when he first decided to create a series of engravings for a deluxe edition of Dante’s classic. He was already the highest-paid illustrator in France, with popular editions of Rabelais and Balzac under his belt, but Doré was unable to convince his publisher, Louis Hachette, to finance such an ambitious and expensive project. The young artist decided to pay the publishing costs for the first book himself. When the illustrated Inferno came out in 1861, it sold out fast. Hachette summoned Doré back to his office with a telegram: “Success! Come quickly! I am an ass!”

Hachette published Purgatorio and Paradiso as a single volume in 1868. Since then, Doré’s Divine Comedy has appeared in hundreds of editions. Although he went on to illustrate a great many other literary works, from the Bible to Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven,” Doré is perhaps best remembered for his depictions of Dante. At The World of Dante, art historian Aida Audeh writes:

Characterized by an eclectic mix of Michelangelesque nudes, northern traditions of sublime landscape, and elements of popular culture, Doré’s Dante illustrations were considered among his crowning achievements — a perfect match of the artist’s skill and the poet’s vivid visual imagination. As one critic wrote in 1861 upon publication of the illustrated Inferno: “we are inclined to believe that the conception and the interpretation come from the same source, that Dante and Gustave Doré are communicating by occult and solemn conversations the secret of this Hell plowed by their souls, traveled, explored by them in every sense.”

The scene above is from Canto X of the Inferno. Dante and his guide, Virgil, are passing through the Sixth Circle of Hell, in a place reserved for the souls of heretics, when they look down and see the imposing figure of Farinata degli Uberti, a Tuscan nobleman who had agreed with Epicurus that the soul dies with the body, rising up from an open grave. In the translation by John Ciardi, Dante writes:

My eyes were fixed on him already. Erect,

he rose above the flame, great chest, great brow;

he seemed to hold all Hell in disrespect

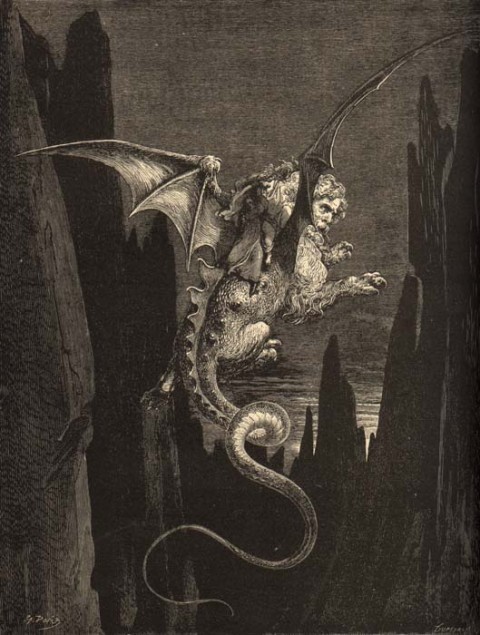

Inferno, Canto XVI:

As Dante and Virgil prepare to leave Circle Seven, they are met by the fearsome figure of Geryon, Monster of Fraud. Virgil arranges for Geryon to fly them down to Circle Eight. He climbs onto the monster’s back and instructs Dante to do the same.

Then he called out: “Now, Geryon, we are ready:

bear well in mind that his is living weight

and make your circles wide and your flight steady.”

As a small ship slides from a beaching or its pier,

backward, backward — so that monster slipped

back from the rim. And when he had drawn clear

he swung about, and stretching out his tail

he worked it like an eel, and with his paws

he gathered in the air, while I turned pale.

Inferno, Canto XXXIV:

In the Ninth Circle of Hell, at the very center of the Earth, Dante and Virgil encounter the gigantic figure of Satan. As Ciardi writes in his commentary:

He is fixed into the ice at the center to which flow all the rivers of guilt; and as he beats his great wings as if to escape, their icy wind only freezes him more surely into the polluted ice. In a grotesque parody of the Trinity, he has three faces, each a different color, and in each mouth he clamps a sinner whom he rips eternally with his teeth. Judas Iscariot is in the central mouth: Brutus and Cassius in the mouths on either side.

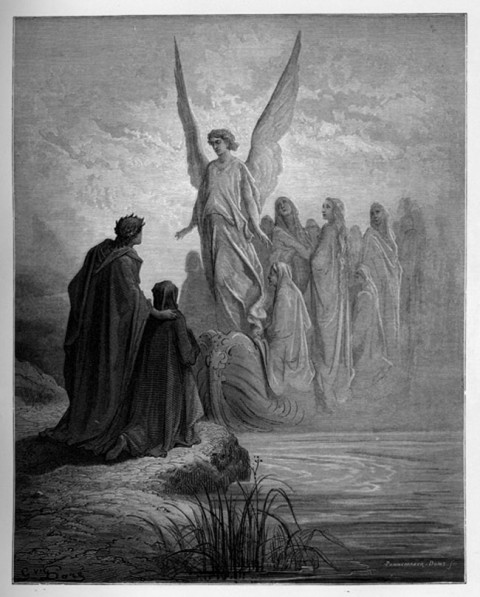

Purgatorio, Canto II:

At dawn on Easter Sunday, Dante and Virgil have just emerged from Hell when they witness The Angel Boatman speeding a new group of souls to the shore of Purgatory.

Then as that bird of heaven closed the distance

between us, he grew brighter and yet brighter

until I could no longer bear the radiance,

and bowed my head. He steered straight for the shore,

his ship so light and swift it drew no water;

it did not seem to sail so much as soar.

Astern stood the great pilot of the Lord,

so fair his blessedness seemed written on him;

and more than a hundred souls were seated forward,

singing as if they raised a single voice

in exitu Israel de Aegypto.

Verse after verse they made the air rejoice.

The angel made the sign of the cross, and they

cast themselves, at his signal, to the shore.

Then, swiftly as he had come, he went away.

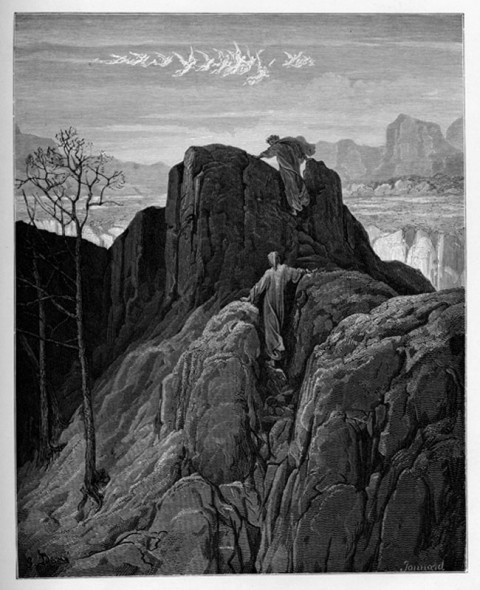

Purgatorio, Canto IV:

The poets begin their laborious climb up the Mount of Purgatory. Partway up the steep path, Dante cries out to Virgil that he needs to rest.

The climb had sapped my last strength when I cried:

“Sweet Father, turn to me: unless you pause

I shall be left here on the mountainside!”

He pointed to a ledge a little ahead

that wound around the whole face of the slope.

“Pull yourself that much higher, my son,” he said.

His words so spurred me that I forced myself

to push on after him on hands and knees

until at last my feet were on that shelf.

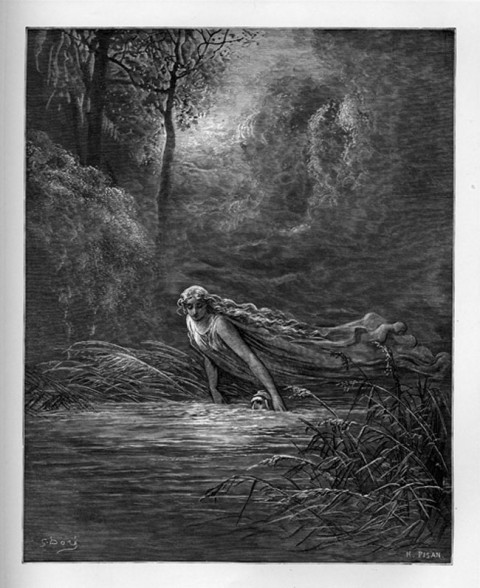

Purgatorio, Canto XXXI:

Having ascended at last to the Garden of Eden, Dante is immersed in the waters of the Lethe, the river of forgetfulness, and helped across by the maiden Matilda. He drinks from the water, which wipes away all memory of sin.

She had drawn me into the stream up to my throat,

and pulling me behind her, she sped on

over the water, light as any boat.

Nearing the sacred bank, I heard her say

in tones so sweet I cannot call them back,

much less describe them here: “Asperges me.”

Then the sweet lady took my head between

her open arms, and embracing me, she dipped me

and made me drink the waters that make clean.

Paradiso, Canto V:

In the Second Heaven, the Sphere of Mercury, Dante sees a multitude of glowing souls. In the translation by Allen Mandelbaum, he writes:

As in a fish pool that is calm and clear,

the fish draw close to anything that nears

from outside, it seems to be their fare,

such were the far more than a thousand splendors

I saw approaching us, and each declared:

“Here now is one who will increase our loves.”

And even as each shade approached, one saw,

because of the bright radiance it set forth,

the joyousness with which that shade was filled.

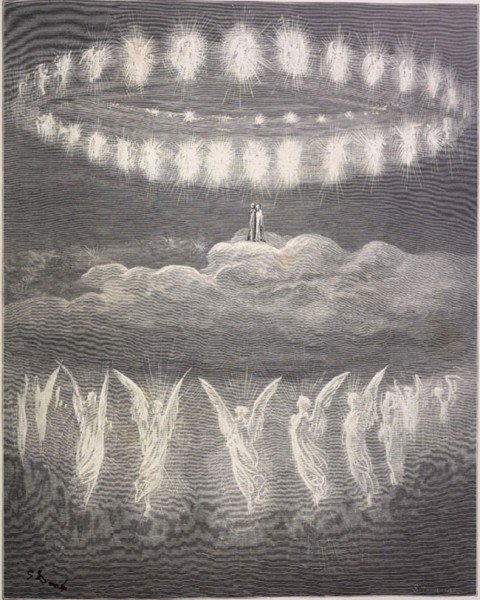

Paradiso, Canto XXVIII:

Upon reaching the Ninth Heaven, the Primum Mobile, Dante and his guide Beatrice look upon the sparkling circles of the heavenly host. (The Christian Beatrice, who personifies Divine Love, took over for the pagan Virgil, who personifies Reason, as Dante’s guide when he reached the summit of Purgatory.)

And when I turned and my own eyes were met

By what appears within that sphere whenever

one looks intently at its revolution,

I saw a point that sent forth so acute

a light, that anyone who faced the force

with which it blazed would have to shut his eyes,

and any star that, seen from the earth, would seem

to be the smallest, set beside that point,

as star conjoined with star, would seem a moon.

Around that point a ring of fire wheeled,

a ring perhaps as far from that point as

a halo from the star that colors it

when mist that forms the halo is most thick.

It wheeled so quickly that it would outstrip

the motion that most swiftly girds the world.

Paradiso, Canto XXXI:

In the Empyrean, the highest heaven, Dante is shown the dwelling place of God. It appears in the form of an enormous rose, the petals of which house the souls of the faithful. Around the center, angels fly like bees carrying the nectar of divine love.

So, in the shape of that white Rose, the holy

legion has shown to me — the host that Christ,

with His own blood, had taken as His bride.

The other host, which, flying, sees and sings

the glory of the One who draws its love,

and that goodness which granted it such glory,

just like a swarm of bees that, at one moment,

enters the flowers and, at another, turns

back to that labor which yields such sweet savor,

descended into that vast flower graced

with many petals, then again rose up

to the eternal dwelling of its love.

You can access a free edition of The Divine Comedy featuring Doré’s illustrations at Project Gutenberg. And for a very different artistic interpretation of the same work, see our post, “Salvador Dali’s 100 Illustrations of Dante’s The Divine Comedy.” A Yale course on reading Dante in translation appears in the Literature section of our collection of 750 Free Online Courses.

Generally speaking, the best illustrations of the Commedia. However, it must be said that the Paradiso ones are less convincing: they are often too ‘classical’ to convey Dante’s more abstract imagery here. See the illustration below for Canto 28 by way of contrast.

Dante’s work was best illustrated by Botticelli in some 100 drawings — an amazing collection that was drawn during the same era and therefore better captures the conceptual depth and moral-social ideas embedded in the divine structure/system.

I actually did not read the book you refer to, but good for you.nI did, however, see the drawings in London at the Royal Academy of Arts back in 2001 and study the era in a couple of academic courses.

I do love Doru00e9, although William Blake’s versions are equally good.

Nossa e muito lindo essas imagem muito belo

hello

could you tell me where to get the copyright for the Dore illustrations? thanks