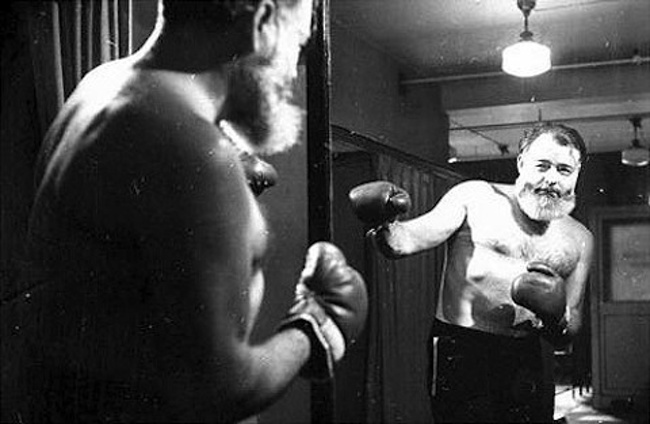

In a 1954 interview in the Paris Review, Ralph Ellison said of one of his literary heroes: “When [Ernest Hemingway] describes something in print, believe him; believe him even when he describes the process of art in terms of baseball or boxing; he’s been there.” I read this thinking that Ellison might be a bit too credulous. Hemingway, after all, has provoked no end of eye-rolling for his legendary machismo, bravado, and maybe several dozen other Latin descriptors for masculine foolhardiness and bluster. As for his “boxing,” we would be wise not to believe him. He may have “been there,” but the real boxers he encountered, and tried to spar with, would never testify he knew what he was doing

Ernest Hemingway wasn’t a boxer so much as he was a “boxer”… a legend in his own mind, a romantic. Hemingway’s friend and sometime sparring partner, novelist Morley Callaghan tells it this way: “we were two amateur boxers. The difference between us was that he had given time and imagination to boxing; I had actually worked out a lot with good fast college boxers.” Or, as the author of an article on the Fine Books & Collections site has it, “Hemingway was lost in the romance of a sport that has no romance to those seriously pursuing it; the romance strictly belongs to spectators.”

As a spectator with pretentions to greatness in the sport, Papa was prone to overestimating his abilities, at the expense of his actual skill as a writer. As he would tell Josephine Herbst, without a hint of irony, “my writing is nothing, my boxing is everything.”

Click for larger image

How did the pros evaluate his self-professed ability? Jack Dempsey, who spent time in Paris in the ‘20s being feted and fawned over, had this to say of Hemingway’s aspirations:

There were a lot of Americans in Paris and I sparred with a couple, just to be obliging…. But there was one fellow I wouldn’t mix it with. That was Ernest Hemingway. He was about twenty-five or so and in good shape, and I was getting so I could read people, or anyway men, pretty well. I had this sense that Hemingway, who really thought he could box, would come out of the corner like a madman. To stop him, I would have to hurt him badly, I didn’t want to do that to Hemingway. That’s why I never sparred with him.

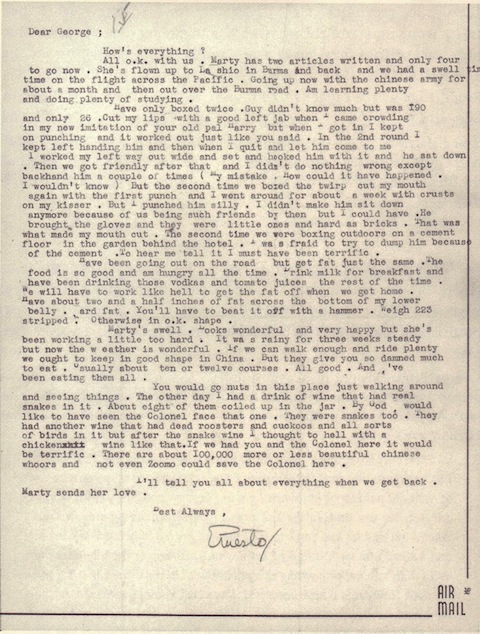

Given Hemingway’s penchant for self-delusion in this matter, he may have interpreted this as Dempsey’s capitulation to his obvious prowess. An even more scathing critique of Hemingway’s bullying… I mean boxing skill … comes to us via Booktryst’s Stephen J. Gertz, who proffers an amusing dissection of the letter above, an unpublished correspondence Hemingway sent in 1943 to George Brown, the writer’s “trainer, coach, friend, and factotum.” Brown, it seems, was kindly, or prudent, enough to encourage his employer in his delusions. However, Gertz writes, “the reality was that anyone who had even the slightest idea of what they were doing in the ring could take Hemingway, who was notorious for foolishly trying to actually fight trained boxers.” He’s lucky, then, that Dempsey practiced such judicious restraint. If not, we may never have seen any fiction from Hemingway after he tried to go a round or two with the champ.

Related Content:

Ernest Hemingway to F. Scott Fitzgerald: “Kiss My Ass”

18 (Free) Books Ernest Hemingway Wished He Could Read Again for the First Time

Ernest Hemingway’s Favorite Hamburger Recipe

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I can totally relate

I agree. But Fighters have their trainers and cornermen and opponents, and writers have their editors and publishers and subjects, but in the end both are out there on their own, wrestling with themselves every time.

Hemmingway hurt you more with his fame then he ever hurt boxers with his skill.

A brilliant write-up! Thanks for offering such clarity on the subject.

A brilliant write-up! Thanks for offering such clarity on the subject.Thanks for sharing