Writer and artist Alistair Gentry once proposed a lecture series he called “One Eyed Monster.” Central to the project is what Gentry calls “the cult of James Joyce,” an exemplar of a larger phenomenon: “the vulture-like picking over of the creative and material legacies of dead artists.” “Untalented and noncreative people,” writes Gentry, “are able to build lasting careers from what one might call the Talented Dead.” Gentry’s judgment may seem harsh, but the questions he asks are incisive and should give pause to scholars (and bloggers) who make their livings combing through the personal effects of dead artists, and to everyone who takes a special interest, prurient or otherwise, in such artifacts. Just what is it we hope to find in artists’ personal letters that we can’t find in their public work? I’m not sure I have an answer to that question, especially in reference to James Joyce’s “dirty letters” to his wife and chief muse, Nora.

The letters are by turns scandalous, titillating, romantic, poetic, and often downright funny, and they were written for Nora’s eyes alone in a correspondence initiated by her in November of 1909, while Joyce was in Dublin and she was in Trieste raising their two children in very straitened circumstances. Nora hoped to keep Joyce away from courtesans by feeding his fantasies in writing, and Joyce needed to woo Nora again—she had threatened to leave him for his lack of financial support. In the letters, they remind each other of their first date on June 16, 1904 (subsequently memorialized as “Bloomsday,” the date on which all of Ulysses is set). We learn quite a lot about Joyce’s predilections, much less about Nora’s, whose side of the correspondence seems to have disappeared. Declared lost for some time, Joyce’s first reply letter to Nora in the “dirty letters” sequence was recently discovered and auctioned off by Sotheby’s in 2004.

I do not excerpt here any of the language from Joyce’s subsequent letters, not for modesty’s sake but because there is far too much of it to choose from. If those prudish censors of Ulysses had read this exchange, they might have dropped dead from grave wounds to their sense of decorum. As far as I can ascertain, the letters exist in publication only in the out-of-print Selected Letters of James Joyce, edited by pre-eminent Joyce biographer Richard Ellmann, and in a somewhat truncated form on this site. Alistair Gentry has done us the favor of transcribing the letters as they appear in Ellmann’s Selected Letters on his site here. Of our interest in them, he asks:

Does anyone have the right to read things that were clearly meant only for two specific people…? Now that they have been exposed to the world’s gaze, albeit in a fairly limited fashion, does anybody except these two (who are dead) have any right to make objections about or exercise control over the manner in which these private documents and records of intimacy are used?

Questions worth considering, if not answered easily. Nevertheless, despite his critical misgivings, Gentry writes: “These letters stand on their own as brilliant and, dare I say, arousing Joycean writing. In my opinion they’re definitely worth reading.” I must say I agree. Joyce’s brother Stanislaus once wrote in a diary entry: “Jim is thought to be very frank about himself but his style is such that it might be contended that he confesses in a foreign language—an easier confession than in the vulgar tongue.” In the “dirty letters,” we get to see the great alchemist of ordinary language and experience practically revel in the most vulgar confessions.

Related Content:

James Joyce Plays the Guitar, 1915

On Bloomsday, Hear James Joyce Read From his Epic Ulysses, 1924

James Joyce, With His Eyesight Failing, Draws a Sketch of Leopold Bloom (1926)

James Joyce’s Ulysses: Download the Free Audio Book

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Dirty? I am upset to learn that people in the intervening years since these letters were penned and posted neglected to wash their hands before handling them.

it should stay personal and if any more secret mails from celebrity’s or non celebrity’s are opened may the reader be struck blind . Here’s looking at you kid .

This isn’t just some celebrity though… This is James Joyce. I think to call him a celebrity is a bit of an insult. That’s like calling Shakespeare a celebrity, or Neruda a celebrity, or Picasso a celebrity (okay I would even maybe understand calling Picasso a celebrity, but Joyce?). It’s just..no… just no. Why would you?.. No.

Now that I was not expecting. Wow, it’s weird we tend to think of famous authors who lived that long ago (I’m in my 20s so it was a very long time ago for me and I’m sure most of you) to somehow be above that level of dirty talk. I didn’t even know they talked that way in those days. But it’s just interesting to see. I kind of want to read more now..

It’s inaccurate to refer to Nora Barnacle as James Joyce’s “wife” in this context. They were not married to each other (nor to anyone else) at the time, nor for another twenty-odd years after the letters in question were written. The two married in the end only because Joyce believed that the mental illness of their daughter, Lucia, arose from guilt arising from her being a bastard, and that it could be cured by his marrying Nora. Lucia was actually schizophrenic and this marriage made no difference to her condition. Joyce was philosophically opposed to marriage and an angry nonconformist in all matters wherein he could openly flout the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church. See the Ellmann biography cited. See also Brenda Maddox’s biography of Nora Barnacle, “Nora.”

In the context of questions about the validity and purpose of examination of such secondary artifacts as these letters of Joyce’s (e.g. “Just what is it we hope to find in artistsu2019 personal letters that we canu2019t find in their public work?”), the omission of the indefatigable complaints of Joyce’s literary executor (and grandson, via Joyce’s son Giorgio), Stephen Joyce, is remarkable. I think that no-one has ever been more vocally negative on this topic than Mr. Joyce has been, and his position is not without reason, however much it may frustrate both prurient curiosity-seekers (the more-educated equivalent of a public that hangs on every indiscretion of Paris Hilton or Britney Spears) and legitimate literary scholars. Mr. Joyce famously announced sometime in the 1980s that he had burned all of the correspondence that he’d had in his possession between Samuel Beckett (James Joyce’s onetime secretary) and his aunt, Lucia Joyce, concerning the love affair that the correspondents either did or did not have. His position has always been that his family’s privacy is perpetually violated, which is self-evident; the case for public examination and discussion of the letters — of the dirty letters in particular, inasmuch as they have no bearing on the published ouvre — is generally less clear.

Always fascinating to see the different takes on this from various sectors of the internet… I’m happy to continue the discussion here, or in the comments of my own blog.nnnnD.Patrick may be interested to know that if you read the linked article I actually do note that Nora was not Jim’s wife at the time of the letters (though she was absolutely his partner and the mother of his children, albeit out of wedlock, and did end up as his wife so it’s a bit pedantic to quibble over the term) and I do discuss the estate/Stephen Joyce’s indefatigable efforts to police the James Joyce legacy. In my opinion these efforts have mostly been far from reasonable or rational, and often silly and obtuse. One particularly petty example was refusing Kate Bush permission to use a few lines from Ulysses in a song.

Imagine writing dirty letters to your wife and then years later people are reading them and blogging about them on the internet lol!

Fifty shades of Joyce!

Mr Gentry: I confess I didnu2019t read the linked article, as Iu2019ve been familiar with the u201cdirty lettersu201d for close to thirty years and donu2019t find them that interesting any longer. Of course I take your point that Nora was functionally Joyceu2019s u201cwife,u201d and I wouldnu2019t normally quibble about it (I myself have never been married in a formal sense, but routinely refer to a specific past partner as my u201cex-wifeu201d). In terms of strict accuracy, though, it isnu2019t correct, and I think that in pointing that out, I was mostly motivated by the writer of the Open Culture entryu2019s having passed up the opportunity to make an additional point about Joyceu2019s rebelliously nonconformist (and to my mind,nforward-thinking) life choices.nnAs to Stephen Joyce, again, I didnu2019t read your linked article, and I should have done so before commenting, but my point, again, was to the writer of the Open Culture entry. I would agree that Mr Joyce has been narrowminded in the extreme. I think it would not be unfair to say that he is hostile to even the most respectful Joyce scholars and uninterested in any discussion of the Joyce legacy that leaves room for shades of grey. My point is that that doesnu2019t mean that his position in the matter can be dismissed as that of a crank any more than it means that his position should be the final word. It is a difficult question.

It may be of interest that there is also a little-seen film about Joyce and Barnacle’s relationship, ‘Nora’ (2000), based on a 1988 biography of the same name by Brenda Maddox, one of many references for which is Ellmann’s ‘Letters’.

It should read “celebrities’ ”. :-)

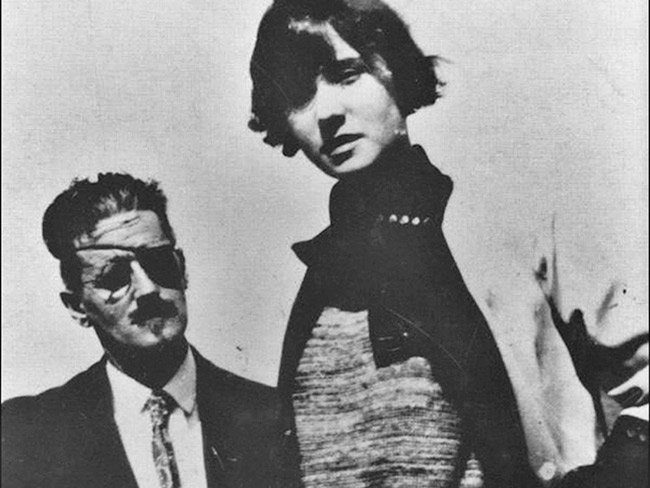

Just by the way, the picture at the top shows Joyce with his daughter Lucia, not Nora.