Fur has flown, claws and teeth were bared, and folding chairs were thrown! But of course I refer to the bristly exchange between those two stars of the academic left, Slavoj Žižek and Noam Chomsky. And yes, I’m poking fun at the way we—and the blogosphere du jour—have turned their shots at one another into some kind of celebrity slapfight or epic rap battle grudge match. We aim to entertain as well as inform, it’s true, and it’s hard to take any of this too seriously, since partisans of either thinker will tend to walk away with their previous assumptions confirmed once everyone goes back to their corners.

But despite the seeming cattiness of Chomsky and Žižek’s highly mediated exchanges (perhaps we’re drumming it up because a simple face-to-face debate has yet to occur, and probably won’t), there is a great deal of substance to their volleys and ripostes, as they butt up against critical questions about what philosophy is and what role it can and should play in political struggle. As to the former, must all philosophy emulate the sciences? Must it be empirical and consistently make transparent truth claims? Might not “theory,” for example (a word Chomsky dismisses in this context), use the forms of literature—elaborate metaphor, playful systems of reference, symbolism and analogy? Or make use of psychoanalytic and Marxian terminology in evocative and novel ways in serious attempts to engage with ideological formations that do not reveal themselves in simple terms?

Another issue raised by Chomsky’s critiques: should the work of philosophers who identify with the political left endeavor for a clarity of expression and a direct utility for those who labor under systems of oppression, lest obscurantist and jargon-laden writing become itself an oppressive tool and self-referential game played for elitist intellectuals? These are all important questions that neither Žižek nor Chomsky has yet taken on directly, but that both have obliquely addressed in testy off-the-cuff verbal interviews, and that might be pursued by more disinterested parties who could use their exchange as an exemplar of a current methodological rift that needs to be more fully explored, if never, perhaps, fully resolved. As Žižek makes quite clear in his most recent—and very clearly-written—essay-length reply to Chomsky’s latest comment on his work (published in full on the Verso Books blog), this is a very old conflict.

Žižek spends the bulk of his reply exonerating himself of the charges Chomsky levies against him, and finding much common ground with Chomsky along the way, while ultimately defending his so-called continental approach. He provides ample citations of his own work and others to support his claims, and he is detailed and specific in his historical analysis. Žižek is skeptical of Chomsky’s claims to stand up for “victims of Third World suffering,” and he makes it plain where the two disagree, noting, however, that their antagonism is mostly a territorial dispute over questions of style (with Chomsky as a slightly morose guardian of serious, scientific thought and Žižek as a sometimes buffoonish practitioner of a much more literary tradition). He ends with a dig that is sure to keep fanning the flames:

To avoid a misunderstanding, I am not advocating here the “postmodern” idea that our theories are just stories we are telling each other, stories which cannot be grounded in facts; I am also not advocating a purely neutral unbiased view. My point is that the plurality of stories and biases is itself grounded in our real struggles. With regard to Chomsky, I claim that his bias sometimes leads him to selections of facts and conclusions which obfuscate the complex reality he is trying to analyze.

………………….

Consequently, what today, in the predominant Western public speech, the “Human Rights of the Third World suffering victims” effectively mean is the right of the Western powers themselves to intervene—politically, economically, culturally, militarily—in the Third World countries of their choice on behalf of the defense of Human Rights. My disagreement with Chomsky’s political analyses lies elsewhere: his neglect of how ideology works, as well as the problematic nature of his biased dealing with facts which often leads him to do what he accuses his opponents of doing.

But I think that the differences in our political positions are so minimal that they cannot really account for the thoroughly dismissive tone of Chomsky’s attack on me. Our conflict is really about something else—it is simply a new chapter in the endless gigantomachy between so-called continental philosophy and the Anglo-Saxon empiricist tradition. There is nothing specific in Chomsky’s critique—the same accusations of irrationality, of empty posturing, of playing with fancy words, were heard hundreds of times against Hegel, against Heidegger, against Derrida, etc. What stands out is only the blind brutality of his dismissal

I think one can convincingly show that the continental tradition in philosophy, although often difficult to decode, and sometimes—I am the first to admit this—defiled by fancy jargon, remains in its core a mode of thinking which has its own rationality, inclusive of respect for empirical data. And I furthermore think that, in order to grasp the difficult predicament we are in today, to get an adequate cognitive mapping of our situation, one should not shirk the resorts of the continental tradition in all its guises, from the Hegelian dialectics to the French “deconstruction.” Chomsky obviously doesn’t agree with me here. So what if—just another fancy idea of mine—what if Chomsky cannot find anything in my work that goes “beyond the level of something you can explain in five minutes to a twelve-year-old” because, when he deals with continental thought, it is his mind which functions as the mind of a twelve-year-old, the mind which is unable to distinguish serious philosophical reflection from empty posturing and playing with empty words?

Related Content:

Noam Chomsky Slams Žižek and Lacan: Empty ‘Posturing’

Slavoj Žižek Responds to Noam Chomsky: ‘I Don’t Know a Guy Who Was So Often Empirically Wrong’

The Feud Continues: Noam Chomsky Responds to Žižek, Describes Remarks as ‘Sheer Fantasy’

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Hahahhah — that punch line was exactly my reaction to Chomsky’s critique. I remember Vonnegut writing something like this in Cat’s Cradle — and I rejected the, “explain it to a twelve year old,” criterion then, too.

I’m with the line attributed to Einstein: “If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.” And my response to reading Lacan and Zizek was the same as Chomsky’s, that underneath all the rhetoric, the ideas were pretty obvious and unimpressive–sound and fury signifying–if not nothing, then less than the hype promised.

Zizek’s defensive responses suggest that Chomsky struck a nerve…and only an attack with a grain of truth in it can do that.

They are both great minds and both make valid points. Zizeks tendancy to verbal flourishing gestures vs noams obsession with empirical factual details. It would be great if they had a head to head interview but it would need a good host to keep the peace. Noam was harshly dismissive imho but at least he provides a counterpoint and counterweight to zizek.

http://terenceblake.wordpress.com/2013/07/24/chomskyzizek-incommensurable-gap-or-sophistic-spat/

Zizek was explained to a young girl, see here: http://terenceblake.wordpress.com/2013/07/26/zizek-explained-to-a-young-girl-douglas-lain-and-his-daughter-emma/

You write “These are all important questions that neither Žižek nor Chomsky has yet taken on directly, but that both have obliquely addressed in testy off-the-cuff verbal interviews…” referring to whether or not thinkers on the left should aim for clarity ” lest obscurantist and jargon-laden writing become itself an oppressive tool.”

Zizek self-evidently doesn’t care about clarity or the consequences of his obscurantism, but Chomsky deals with these issues very thoroughly (spelling out the consequences) in a 9 minute 2011 video very easy to find on YouTube: “Chomsky on Science and Postmodernism” at

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OzrHwDOlTt8

I think the point Zizek is trying to state is simply that one cannot subtract itself from ideology; since Kant we know there is no such thing as pure unbiased objectivity. In these line of thought, Chomsky reveals himself as much more ‘dishonest’ than Zizek, since he does not admit the underlying criteria (ideology) that sustains his theory. In fact, it is a really naive approach to rely on ’empirical data’, not acknowledging the violence exercised onto reality (object or noumena if you prefer) when questioning and interpreting facts. On the other hand, Zizek translates the discussion onto a much more political level, since there is more of a political –in all senses of the word–context or subtext in the essence of philosophical inquiry (regarding the innumerable amount of assumptions that guide philosophical thought or reflection).

Dan, you may be interested in this post we did on that very interview (which has nothing to do with Zizek): http://www.openculture.com/2013/07/noam-chomsky-calls-postmodern-critiques-of-science-over-inflated-polysyllabic-truisms.html

Also, note that Zizek, in the text above, rejects the label “postmodernism” and claims to respect the empirical sciences, not reject them.

Dan says: “Zizek self-evidently doesn’t care about clarity or the consequences of his obscurantism”

1) “self-evidently,” as used in this sentence, is a textbook example of “obscurantism” that attempts to add rhetorical weight to a statement, while actually detracting from clarity.

2) Zizek’s work in quite clear to anyone with a background in the fields he is writing in. Someone unfamiliar with the vocabulary of 20th century physics will have difficult with Einstein as well. Did you also dismiss Nietzsche when you didn’t comprehend his meaning in the first 20 pages you put yourself through? Sorry, but difficult ideas will be difficult to comprehend for people who aren’t capable or not willing to put in the effort.

3) The narcissism of blaming a writer’s “obscurantism” is such a blatant transference of the reader’s own intellectual failure to comprehend. Sadly, the trend seems to be exploding in the last decade.

So sad and pathetic. Just notice what Zizek wrote: “…how could I have done it [give evidence] in an improvised reply to an unexpected question?” He’s saying, how could I give evidence for my claim, since I didn’t expect the question. That’s what he wrote in his essay. So unless he expects the question in advance, hisbrilliant genius can’t back up a simple claim. This poor man is so irrational it really makes me wonder.

Zizek, you’re a sad and pathetic loser. You’re not even worth a criticism.

Zizek is right about one thing, but everyone else on this thread is wrong… Very wrong.

@Vince: your reference to the authority of Kant is ironic, for Kant is a hard core emirical realist, not a relativist. Although his transcendental idealism suggests a limit for possible knowledge it is a limit beyond which there is nothing more to know. It is part of his argument (CPR) for the possibility of “pure unbiased objectivity” regarding empirical facts.

But where is the very detailed response by Zizek? Not that it really would interest me, considering the silly quotations (I am not saying that everything is just different stories, but there are different stories…)from it, but anyway…

I fasten pieces of wood together for a living, and cannot use terms like “continental philosophy” or “obscurantist” in a sentence (Oh no- I just did; should I have a cup of coffee or kill myself?).

That said, I would prefer Mr. Chomsky as my tax preparer, and Mr. Zizek as my hospice counselor. If Felix and Oscar aren’t already stealing furtive gropes behind the boiler, then they clearly must be fused together. The hip. This would avoid the head vs. tail conflict in a human centipede-type assembly.

I’m sure each would cheerfully replace/modify their pants to be 50 percent of a perfectly logical yet emotionally intelligent being. A perpetually bickering bicameral Janus super-genius to explain democracy to the world.

Or absent that, a dance off.

I dislike Zizek. I agree with Chomsky’s criticism. His claim that he represents ‘continental philosophy’ and thus the criticism against him, is vain — both as in representing his vanity and in being empty of content.

Very sad on Zizek’s part that he doesn’t care enough about the empirical to get things right about Rwanda in his most recent comments (“Some Bewildered Clarifications”). He speaks of “the mass slaughter of Hutus by Tutsis in Ruanda in 1999. Indeed, the US-backed Kagame regime has been slaughtering his opponents, often, but not exclusively Hutus, since October 1990. And especially since, again with US-backing, Kagame and Museveni (US-backed dictator of Uganda just to the north of Rwanda) attacked Kivu Province, in the Dem Rep of Congo in 1996, launching the massive genocide that continues to this day in Kivu. But, Zizek seems to want to be referring to the (false) mainstream story in his remark wherein the Hutus allegedly slaughtered the Tutsis for 100 days following April 6, 1994, when the plane carrying then-president of Rwanda Juvenal Habyarimana and then-president of Burundi Cyprien Ntaryamira was shot down by Kagame’s RPF.

It’s amazing that Zizek doesn’t care about the facts enough to get such things straight.

I recall reading Chomsky’s Syntactic Structures. Could not make much sense of it. A reduction of his thesis – its philosophical implications – found in the encyclopedia of Linguistics was more elucidating. Almost to the point of banality. And I remember reading Zizek who was expounding on garbage. The piece was at least funny. The author concluded that we should somehow love the junk we produce. I can trace and explain his train of thought to a 12 years old – from start to finish, no problem. Syntactic Structures? No so sure about this one without a reference to the encyclopedia. As far as this debate is concerned, it’s weird how Chomsky appoints himself a judge in what appears to be the question of personal cognition. People do read Zizek – not that they are forced to do so. Which means they do understand something in his writing at start and can relate to topically. Difficult as it may be to some and impenetrable to many others, his writing speaks to them. It means at least something, I presume. But Chomsky says it should not.

O my did I see terence blake weighing in on this? O jeez, this might get interesting,except that his work is really an overdone elaborate copycat of that other french ‘penseur’ of the obscure left.. Derrida? Blake is going to try to make this all very ‘individuated’ and very Deleuzian who by the way, Zizek, took the piss out of in his book Organs without Bodies. I think what’s his name at Znet started this whole thing, Michael Albert . He was the one that asked Chomsky what he thought. But who cares really? Chomsky thinks he is a prophet but forgets all the things that make up the day to day lives of millions who don’t necessarily agree with him. Its refreshing to see him get his own. He can’t take on Zizek, he’s out of his depth. He’s already lost, and I bet ten to one he won’t even bother replying to Zizek’s excellent response at Verso Books.

From my response at: http://savioni.wordpress.com/2013/07/27/chomsky-v-zizek/

Chomsky v. Zizek

Posted on July 27, 2013

Various articles, blogs have covered an alleged debate that has sprung up in response to Noam Chomsky’s insult of writers like Slavoj Zizek, who Chomsky believes posture, by using fancy terms like polysyllables and pretend to have a theory when they have no theory whatsoever, see: http://veteransunplugged.com/theshow/archive/118-chomsky-december-2012, anyway, here is my take on the event(s):

See also:

A. http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2013/jul/19/noam-chomsky-slavoj-zizek-ding-dong;

B. http://www.openculture.com/2013/06/noam_chomsky_slams_zizek_and_lacan_empty_posturing.html;

C. http://www.openculture.com/2013/07/slavoj-zizek-publishes-a-very-clearly-written-essay-length-response-to-chomskys-brutal-criticisms.html; and

D. http://www.openculture.com/2013/07/slavoj-zizek-responds-to-noam-chomsky.html, for example.

Chomsky:

1. Zizek provides no theory.

Theory:

1. Tested general propositions

2. Regarded as correct

3. That can be used to explain

4. That can be used to predict

5. Explanations of which status still unproven and subject to experiment.

A. In Zizek’s book The Parallax View, he proposed that anecdotes he provided share an expressed “Occurrence of an insurmountable parallax gap, the confrontation of two closely linked perspectives between which no neutral common ground is possible.”

B. In Chomsky’s book On Language, Chomsky said, “There is no very direct connection between my political activities, writing and others, and the work bearing on language structure, though in some measure they perhaps derive from certain common assumptions and attitudes with regard to basic aspects of human natures. Critical analysis in the ideological arena seems to be a fairly straightforward matter as compared to an approach that requires a degree of conceptual abstraction. For the analysis of ideology, which occupies me very much, a bit of open-mindedness, normal intelligence, and healthy skepticism will generally suffice.”

C. Zizek likes theoretical thinking.

D. Chomsky’s “Generative grammar…attempts to give a set of rules that will correctly predict which combinations of words will form grammatical sentences.” As a poet, I find this proposition ridiculous or at least mechanical and empty, but of course I understand it. It seems at times words come to me in an arbitrary fashion. I can work with magnetized words and arrange them in such as way as to adhere to the surprise combinations that can be afforded after a little attention. One day, I expect a poet will be made to contest a computer in the act of writing a poem based on Chomsky’s theory. And the poet will know at the outset that given any number of possible sequences, a line will be formed that will serve the same function that a line in a good poem might. Because the process of writing poetry is about writing words that make us think about ideas and in so doing we think within ourselves about things that were once outside of us. They become meaningful and important because they catch our aesthetic eye, our love of language and ideas.

F. Zizek is a philosopher. He likes to study the nature and origin of ideas. He likes theorizing of a visionary or impractical nature.

G. Chomsky becomes a philosopher when he says Zizek has no theory. And Chomsky admits that “There is no very direct connection between [his] political activities, writing and others, and the work bearing on language structure, though in some measure they perhaps derive from certain common assumptions and attitudes with regard to basic aspects of human natures” and “Critical analysis in the ideological arena seems to be a fairly straightforward matter as compared to an approach that requires a degree of conceptual abstraction. For the analysis of ideology, which occupies me very much, a bit of open-mindedness, normal intelligence, and healthy skepticism will generally suffice.”

H. Chomsky said we don’t need critiques of ideology we just need the facts because there is already a cynicism of those in power. He exemplifies this with the fact: ‘This company is profiting in Iraq.’

I. Zizek said daily life is ideology. He said that Krugman said that the idea of austerity is not good theory. It was just a conclusion drawn by those in power to fix the economy, Krugman said.

J. Zizek in effect calls Chomsky a cynic when he says that cynics don’t see things as they really are. He cites Chomsky’s inability to see that the Khmer Rouge or Stalinist Russia were horrible, since Chomsky did not consult primary sources, i.e. public discourse.

K. Zizek is comfortable with the efficiency of theoretical thinking.

L. Even Chomsky mentioned that he has been asked to speak on mathematical linguistics and yet he is not credentialed therein. He is self-taught. He said the mathematicians could care less. “What they want to know is what I have to say…whether I am right or wrong, whether the subject is interesting…whether better approaches are possible — the discussion dealt with the subject, not with my right to discuss it, p. 6.”

M. Zizek provides theory. In the act of speaking/writing, his ideas as words in the English language are proposals, often general, and they are tested as they hit the air or even in his mind they are being heard. We often know what sounds correct. Our beliefs, attitudes, and values are shared given the general consensus inherent in experience. Thereby, they are regarded as correct or incorrect. These propositions of his are used to explain and predict, and at times they are explanations that are unproven and subject to contemplation and the rigors of experimentation, but Zizek in his assertions, no matter the weight and complexity of his words, is legitimately explaining what we may wish to ignore or feign the desire to decipher, define, or connote.

N. The fact that Chomsky said that grammar contains a rudimentary generative syntax implies a universality of language. And Lakoff has said this and I believe Merleau-Ponty did too. But, this commonality of the capacity to think in words in complement to Chomsky’s desire that simplicity be used relates to the metaphorical world. And whether we deduce or empirically test, we remain bound to language to express. Thomas Kuhn said our biases are always there. An insect would roll his eyes at our conclusions. We are stuck in this world self-entertaining. And for Chomsky to attack a man certainly as entertaining as he is in bad form. Empiricism and deduction are no greater than theorizing and espousing, like the mathematicians, we all just want to know what Zizek has to say…whether he is right or wrong, whether the subject is interesting…whether better approaches are possible and the discussion dealt with the subject, not with Zizek’s right to discuss it. — Mario Savioni

“[M]ust all philosophy emulate the sciences? Must it be empirical and consistently make transparent truth claims?”

To the first question, perhaps not; perhaps not empirical either. But if consistency, transparency and truth are all absent, would there be any philosophy left? It is hard to know what you would end up with.

It is trivially true that obscure expressions can neither share nor produce determinate meanings. Yet some “theorists” or their supporters seem to believe in hidden meanings, e.g. that a play with obscure expressions, or a ‘discourse’ on their appropriate interpretations, would magically reveal what is hidden for those who merely read with ‘logocentric’ eyes..

But without logic or facts “theories” are merely differed compared by the psychological or sociological effects of their use of “advanced” or theoretical looking language, intended to convince or persuade without reason.

The late Denis Dutton described one of Judith Butler’s infamously obscure expressions like this:

“To ask what this means is to miss the point. This sentence beats readers into submission and instructs them that they are in the presence of a great and deep mind. Actual communication has nothing to do with it.”

http://denisdutton.com/language_crimes.htm

@Jkop: I said since Kant because is from his revolutionary transcendental idealism that the naive empirical approach collapses, leading thinkers like Fichte, Schelling and Hegel into idealism (which I’m sure Kant wouldn’t subscribe, although one can argue that the core of idealism is in the KRV). You are deeply wrong when you state that Kant was a “hard core empirical realist”, when he actively presents arguments to refute empiricism (in the figure of Hume for example). In order to be honest with yourself, you should acknowledge that since XVIII century, there is no certainty regarding objectivity, at least not without relying on a huge amount of dogmatic assumptions.

@Vince: Indeed, Kant actively presents arguments to refute empiricism. You’re certainly right about that :) But he also refutes rationalism, subjectivism, mysticism, and, above all, scepticism, i.e. the belief that knowledge would be uncertain. You claim the contrary, which is ironic.

For if Hume would be right about the lack of necessity, then scepticism would follow regarding certain knowledge of empirical facts. Kant’s counter-argument is that the necessity comes from us, hence transcendental idealism to justify empirical realism

This is as close as one can get to certain possible knowledge of empirical facts. Yet Kant is widely misrepresented, partly because of his complicated style of writing. But Kant is the opposite of a sceptic.

Chomsky disagreed with Foucault, but seemed to believe it was a disagreement of substance. With Zizek, there’s not enough substance to warrant a disagreement, just a dismissal.

Having read Chomsky’s book On Language and Zizek’s book The Parallax View, I found Chomsky to be less intellectually entertaining. Chomsky talked about a Universal grammar, while Zizek blew me away on a number of topics, most interesting of which was a discussion of Henry James’ book The Wings of the Dove as well as the concept of anti-anti Semitism. Chomsky clearly defeated Alan Dershowitz in a debate about Israel (See:

http://www.democracynow.org/20… but he did not defeat Foucault in the sense that as was stated in the debate by Elders that Foucault was “working on a completely different level and with a totally opposite aim and goal,” which Foucault agrees to when he says: “Therefore I have, in appearance at least, a completely different attitude to Mr. Chomsky apropos creativity, because for me it is a matter of effacing the dilemma of the knowing subject, while for him it is a matter of allowing the dilemma of the speaking subject to reappear.”

I think Chomsky has an agenda, where he states, for example: “What I’m arguing is this: if we have the choice between trusting in centralized power to make the right decision in that matter, or trusting in free associations of libertarian communities to make that decision, I would rather trust the latter. And the reason is that I think that they can serve to maximize decent human instincts, whereas a system of centralized power will tend in a general way to maximize one of the worst of human instincts, namely the instinct of rapaciousness, of destructiveness, of accumulating power to oneself and destroying others.” This is versus Foucault’s position, where he states: “I would say that our society has been afflicted by a disease, a very curious, a very paradoxical disease, for which we haven’t yet found a name; and this mental disease has a very curious symptom, which is that the symptom itself brought the mental disease into being… You can’t prevent me from believing that these notions of human nature, of justice, of the realization of the essence of human beings, are all notions and concepts which have been formed within our civilization, within our type of knowledge and our form of philosophy, and that as a result form part of our class system; and one can’t, however regrettable it may be, put forward these notions to describe or justify a fight which should-and shall in principle–overthrow the very fundaments of our society. This is an extrapolation for which I can’t find the historical justification,” (See: http://www.chomsky.info/debate.…

Chomsky might be contradicting himself when he said in his book On Language that, “Language serves essentially for the expression of thought… Perhaps the instrumentalist conception of language is related to the general belief that human action and its creations, along with the intellectual structure of human beings, are designed for the satisfaction of certain physical needs (food, well-being, security, etc.). Why try to reduce intellectual and artistic achievements to elementary needs?” (From:

Language and Responsibility, pp. 88–89.)

He was critical of George Lakoff too when he said that Lakoff was “Working on ‘cognitive grammar,’ which integrates language with nonlinguistic systems.” Chomsky said he didn’t “See any theory in prospect there,” Ibid, p. 150. Chomsky said that Lakoff proposed “arbitrary” relations between meaning and form.

If we take the idea of “Anti-anti Semitism,” for example, what Zizek is talking about is fundamentally important. His assertion is that people are changing their once sacred and protective views of Israelis because it would appear that like an abused child, Israelis have grown up to abuse. It is a slow awareness but one that legitimizes Zizek because his theory both predicts the future and explains the present and so the idea is not arbitrary, but rather it is profound.

I think Lakoff and Zizek have a lot in common, where Lakoff’s book Philosophy in the Flesh talked about how science was no greater than what man could conceive through the context of his mind as in metaphors, which is a bit like Chomsky’s idea of organs having a memory and that language was already built in.

Whenever someone attacks another person because of the type of language that person uses, as in Chomsky’s statement: “I’m not interested in posturing–using fancy terms like polysyllables and pretending you have a theory when you have no theory whatsoever,” it fails to address the meaning of those terms separately or conjoined. I found Zizek to be clear and informative, where I found Chomsky to be narrowly focused and repetitive.

I think Chomsky may be loosing his sense of humor and taking himself too seriously. How can someone “kind of like” another person? The world is full of ideas. Philosophers look over the shoulders of scientists and discuss the application of discoveries. Chomsky says that we never change, which is a bit like saying that what scientists discover is nothing new. And Lakoff would agree. Chomsky generalizes the “posturing” Paris intellectuals and I believe he commits the sins of the argument ad hominem and arbitrariness he blames Lakoff for. I believe he is projecting his own failures to change a world that has allowed him to theorize. Funny, he says, “Humans may develop their capacities without limit, but never escaping certain objective bounds set by their biological nature.” (Chomsky, Ibid., p. 124)

Your fascination with this empty argument is rather strange. I also find your description of Zizek’s blog as ‘very clearly written’ amusing, as though it were something he was mostly incapable of doing. You write as though you were balanced, but your contempt of ‘theory’ as you call is obvious in most of what you write.

@Mario: you say that Chomsky’s attack “fails to address the meaning of terms separately or conjoined”. But Chomsky’s point is that Zizek’s use of terms offers no conclusions nor a theory to address. Hence the attack on Zizek’s use of language.

For example, some terms may be too indeterminate (e.g. sweeping hegelian abstractions), or their conjunctions violate or evade argument form from which conclusions could be made. It is therefore not theory in any true sense of the word.

Nor is it poetry. Poets don’t usually label their poems theory, and if a poem is expressed obscurely, then it would be indeterminately anything and not specifically a poem. Obscurity has lttle to do with poetry or theory, but more with failure.

In Russia, Edward Snowden is being tortured; what we and most western audiences don’t know is that, given the interrelation between US and Russia oil interests, a secret deal may have been struck between Obama and Putin: russia grants a phoney-baloney asylum…etc. etc. The point is that Snowden no longer matters; he IS a talking point, but, honestly, I’m just so relieved that young Hannah Anderson is safe…I mean.…FUCK!

@Jkop, What I meant by Chomsky’s failure to address the meaning of Zizek’s terms is that if you read Zizek and if you define the words he uses, you will come up with what I found, which is that Zizek is clear.

Zizek’s statements offer conclusions. His whole book Parallax View, for example, is a thesis/theory about two sides of an intellectual coin.

I am really put off by this idea that Zizek does not theorize. His propositions are theories about reality.

When I talk about Thomas Kuhn, I am addressing paradigm shifts, where, which I am sure you know, old great theories are replaced by other great theories, which will also be replaced. What that says is that it turns theories into postulates that seem to work as the legal concept known as shifting sands. We are so sure until someone comes up with a better idea or theory. Lakoff talks about metaphors. Our theories are metaphors for how reality works. As human beings, we can think in terms that our brains can define and share. When we communicate great theories, we reduce them to metaphorical symbols or formulas and I believe great theories are born through insights that are then proven. Ideas give birth to accurate ways of seeing the world or at least new ways of seeing. Each idea about something is a theory.

Chomsky attacks talking. He attacks the generative nature of language. He hates that Zizek or Foucault, I am sure, or any other number of writers, who tool up complex language to define something that he thinks should be made simple for a 12-year-old to understand. Well, I disagree because that would be to take the joy out of reading Jean-Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness or Heidegger’s Being and Time or Foucault’s section on “Madness, The Absence of an Oeuvre,” for example.

The words these great minds use create vast landscapes of ideas and thoughts, they bring us to a greater appreciation of who we are because we are not left on a single plane of understanding or appreciation. When I read Heidegger’s Being and Time, I felt he understood, as I felt, that there are billions of things going on at once, which is easily understood by a 12-year-old because of the capacity of the intellect or sensitivity to life. Heidegger wrote in such a way as to both manifest his point and to alter the reader’s mind. It was being in the mind of the genius as he thought about being and time.

What defeats Chomsky or makes his argument disingenuous is his statement about mathematical linguistics and his lack of credentials and yet he gives talks and the mathematical linguists listen because he might say something that is correct or new and also correct. Being credentialed does not a theory make.

Zizek can use the English language anyway he wants, because in the end we simply take our dictionaries and define the terms and address the grammatical constructs, which have meaning. We can test his theories in terms of our experience/experimentation.

I do not agree with your assertion that some of Zizek’s terms are indeterminate. None, as far as I can tell, are thus. They are based in the English language or at least they are translatable.

Nothing I have read of his evades argument. His words argument inherently, for anything a person says is arguable.

It is theory in the sense that one definition of the word theory is: “A contemplative and rational type of abstract or generalizing thinking, or the results of such thinking.” (Taken from Wikipedia).

As a poet, I disagree that poetry is not theory. It is an emotive synthesis of reality akin to Einstein’s Theory of Relativity. It works on the plane of emotion, while Einstein’s works on the plane of explaining the phenomena known as dilation when measuring quantities that are relative to the velocities of observers, and where space and time should be considered together, but where the speed of light is unvarying for all observers. (Taken from Wikipedia)

Both poetry and Einstein’s theory are trying to communicate what reality is, the poet in emotive terms, Einstein on even more abstract terms and hence Einstein’s obscure postulates that could just as easily be called indeterminate, except that he puts words to the postulation, just as the poet puts words to her postulations. (Please read POETRY IS NOT A PROJECT by Dorothea Lasky:

http://www.uglyducklingpresse.org/archive/online-reading/poetry-is-not-a-project-by-dorothea-lasky/ to know what I mean by the similarities between poets and scientists.)

When I write the following, for example, I am contemplating a rational type of abstract or generalized thinking. It is a theory about a moment in a cafe, where I am looking through the front window at a woman. I hope to be with her just by her crotch, which is what I want of a particular design, and where I come to this point, time and time again, such that in terms of the measurements of these various quantities they are relative to the speed of my observation, to the similar observations of others, who also come to this point, dilating, where the space and time of the moment should be considered together as the light in knowing this is invariant:

In Truth

It looks like rain but it isn’t, thunderclouds but they aren’t. Back in Milano, the cafe, that is, where I peer through the shattered glass of the front window, hope walks by… I can’t see faces just the crotches of slim women — what I want in a lover. Time and time again I come to this point. (The poem, “In Truth,” page 14, Uncertainty, by Mario Savioni, © 2000 and revised in 2011, go to: http://www.blurb.com/b/2134039-uncertainty)

Both Einstein and poets are using the English language to explain a phenomenon they have experienced or in the poet’s expressive obscurity he too is communicating what is true because obscurity may be his theme. There is no failure in obscurity; sometimes that’s the point. I once reviewed an artist’s work and found her work ugly, but it was in that ugliness that she was making a point about reality that was true. At times ugliness is true and truth is always beautiful, even though it may be asymmetrical (See: http://chronicle.com/article/When-Beauty-Is-Not-Truth/136803/).

I think you guys are not getting the point. Zizek is a great mind and Chomsky is disingenuous or at least forgetful that ideas are the stuff of theory and words are definable and so we are never lost to obscurity. If so, we are not working hard enough.

Surely Zizek can list the theories and accomplishments of note, that have had an effect on the audience meant to be affected (namely, the vast majority of people, the working class), deriving from the continental tradition. Marx turns in his grave at these obfuscatory academics and their worship of traditional philosophical methods.

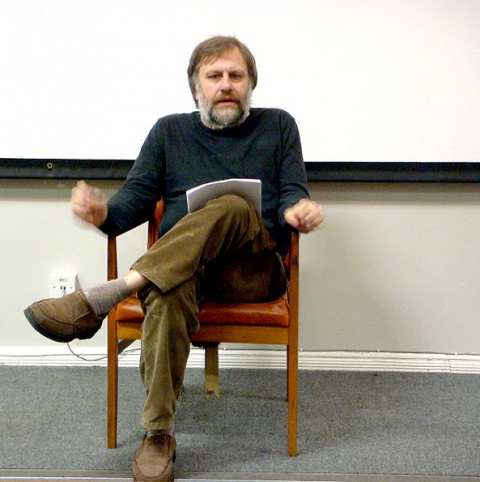

A clear difference between Chomsky and Zizek can be seen in their visual style. Chomsky speaks in a dry monotone, almost never moving any part of his body, relentlessly bludgeoning us with fact after fact to back up a single thesis: that America is essentially and almost one dimensionally definable as an imperialist power and it must be resisted at all levels. Listening to Chomsky is like being forced to carry a heavy stone up a very long grade. nnnWatching Zizek is like being at the circus. Everything is moving as he throws out perspectives that challenge us to view our world with different eyes, different thinking structures, different perceptions. For Zizek there is no monolithic ‘scientific’ point of view that dominates all discourse, but a fluid and constantly experimental process of exploration that shifts in tone, color and conclusion with every bit of new input. Zizek considers ‘facts’ from as many angles as possible. He is occasionally elusive as he challenges us in a good humored way to keep up with him. From Zizek’s perspective we enter a future with a sense that things are very much unresolved and that the most useful approach is one that challenges every form of dogma that imagines reality to be something set in concrete. A nnnChomsky speaks as if all of our perceptions can be resolved by simply viewing the ‘facts’ objectively. Beneath the supposed objectivity is a set of dogmatic assumptions that cannot be questions and that carry with them an air of stifling and oppressive authority. Not to say that his analysis and point of view isn’t valuable as an alternative to the one presented in the mainstream media, but after years of listening I’ve come to feel his lectures are a form of self-torture that lead me nowhere.

@Melcher, you are arguing the man: ad hominem.

narcotizing fog [occasionally mildly amusing] is the only apt description of Mr. Zizek’s usual writing style. He can be clear when he wants to be which means it is intentionally fog. call it ‘fog for fun’ that it makes him inaccessible simply makes him less useful and relevant and, a mere entertainer.

Probably one of the best Zizek interpreters — Yana Novak: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kx_PeTFgpT8

Indeed I am. It was, in fact an encounter with the person, Chomsky, at a lecture in New Mexico that left me feeling (yes, I’m talking about feelings) absolutely enervated and uninspired and bereft of any impulse toward positive action. This experience has led me to see more and more why the Left in both America and England have lost the attention of the very people whom Chomsky idealizes, the working poor and the middle classes. To begin with a dogmatic premise and then to follow it up with nothing more than a relentless litany of “facts” purporting to support that dogma is both demoralizing and boring, not to mention elitist in the extreme. While Zizek engages with people Chomsky pontificates.