Since his improbable but riveting rise from put-upon, cancer-stricken chemistry teacher Walter White to sociopathic meth kingpin Heisenberg, Bryan Cranston’s character in Breaking Bad has come to embody all of the characteristics of an ancient despot: cunning, paranoia, the nursing of old wounds and pretensions to undeserved greatness. It seems perfectly in character, then, that the show’s producers would tease the final season with the ominous and dusty clip above, with Cranston reading Percy Bysshe Shelley’s sonnet “Ozymandias,” a poem about the hubris of another desert tyrant—well-known for his megalomaniacal folly—Ramesses II (also known by a transliteration of his throne name, Ozymandias).

The speaker of Shelley’s poem meets a traveller from an “antique land,” who describes an immense statue, broken to pieces and lying strewn in the desert where “Nothing beside remains.” On the statue’s pedestal, a sculptor has inscribed the words, “My name is Ozymandias, king of kings. / Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair.” As Slate describes the teaser’s match-up:

The poem echoes all the show’s big themes: the mythology of evil, the nuances of morality, the arc of coronation and decay. The images, on the other hand are fleeting—mostly New Mexico desert and suburbia, though we end with a lingering shot of Heisenberg’s dusty, worn hat resting, like the poem’s once-colossal statue.

Fans of the show familiar with the poem’s most pronounced theme, the fleeting nature of empires, no matter how great, will know to anticipate the fall of Heisenberg in some spectacular fashion, though all we have so far are the vague hints of Walter’s escalating violence and paranoia from the last few episodes. Cranston seethes the poem’s most famous line—that one about despair (and the source of the poem’s central irony)—with particular menace.

The poem’s imagery, so common to the early nineteenth century Egyptology of Shelley’s time and after, was allegedly inspired by a passage in Roman-era historian Diodorus Siculus describing just such a statue. Also fueling Shelley’s imagination were the Napoleonic archaeological finds in Egypt, including news of the 1816 discovery of a massive Ramesses II statue by Italian explorer Giovani Belzoni (who sold it to the British Museum in 1821). Shelley wrote “Ozymandias” in competition with a friend, financier and novelist Henry Smith. Smith’s submission, “In Egypt’s Sandy Silence,” came first.

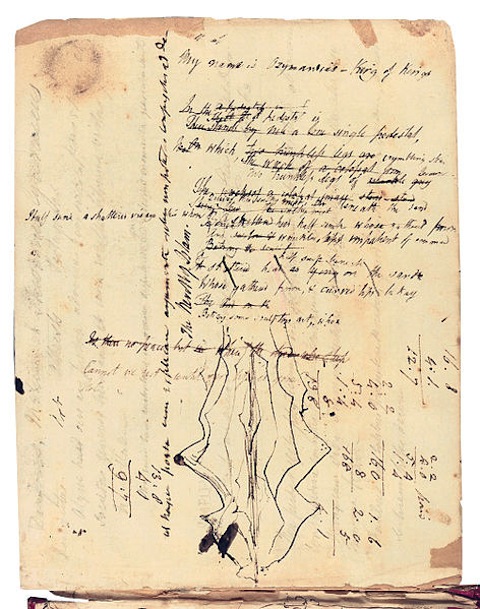

Critic and writer Leigh Hunt published both poems in 1818 editions of his monthly magazine The Examiner. While Smith’s poem barely rises to the occasion, more clumsy parody than serious literary endeavor, Shelley’s—like the sculptor’s inscription in his poem—has outlasted the empire of his day and lives on in the microcosmic TV representations of our own imperial works. Above, see an 1817 draft copy of Shelley’s iambic pentameter sonnet, worked over with corrections and revisions. Below see the fair copy he sent to Hunt for publication. Both copies reside at the Bodleian Library.

Related Content:

Inside Breaking Bad: Watch Conan O’Brien’s Extended Interview with the Show’s Cast and Creator

Discovered: Lord Byron’s Copy of Frankenstein Signed by Mary Shelley

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him at @jdmagness

It’s not a sonnet.

Well, the rhyme scheme isn’t. But the line count works. oops. Don’t take away my Master’s Degree. It’s early in the day.

Correction: Shelly’s came first.

While Smith’s version is good, it is not as intricate or as subtle as Shelly’s, and that is possibly the main reason why Shelly’s endured. I have a feeling that it was Smith’s version that would’ve been more appreciated at that time, like all things easy.

Yes, Andrew, the rhyme scheme is idiosyncratic, but it fits the form closely enough to still be considered a sonnet.

“SAY MY NAME!”

Interesting poetry