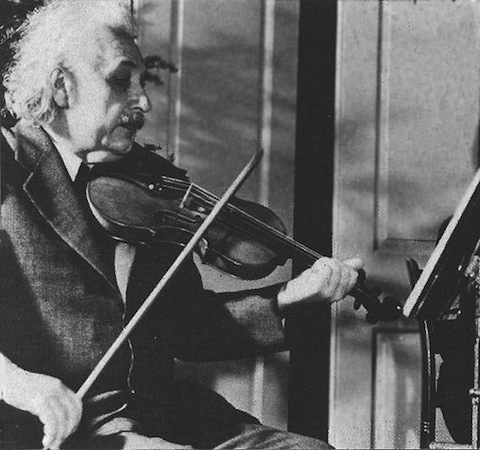

At the height of Albert Einstein’s popularity, the public knew him not only as the world’s foremost theoretical physicist, but also as an enthusiastic sometime violinist. As a publication for the 2005 “World Year of Physics” puts it: “to the press of his time… Einstein was two parts renowned scientist, one jigger pacifist and Zionist fundraiser, and a dash amateur musician.” While this description may get at the public perception of his composition, Einstein himself seems to have favored the musician over all of his other “parts.” “Life without playing music is inconceivable for me,” he once said, “I live my daydreams in music. I see my life in terms of music… I get most joy in life out of music.”

The famous scientist never travelled without his beloved violin, “Lina.” His affair with music began with violin lessons in Munich at the age of 5. However, his early experiences with the instrument seem at best perfunctory and, at worst, antagonistic (one anecdote has him throwing a chair at his teacher, who left the house in tears).

He did not truly fall in love until discovering Mozart at age 13. A high school friend reported to biographer Carl Seeling that at this time, when the young Einstein’s “violin began to sing, the walls of the room seemed to recede—for the first time, Mozart in all his purity appeared before me, bathed in Hellenic beauty with its pure lines, roguishly playful, mightily sublime.”

This gushing recollection must inevitably prompt the question, raised in every account of Einstein and music—was he really any good? Since he played mostly for his own enjoyment, the answer seems irrelevant; yet, as particle physicist Brian Foster says in the video above, Einstein was “competent.” In his Berlin years, he played with renowned musicians like Austrian violinist Fritz Kreisler and pianist Artur Schnabel (as well as with founder of quantum theory, Max Planck). His scientific notoriety garnered invitations to perform at benefit concerts. One critic remarked, “Einstein plays excellently. However… there are many violinists who are just as good.” Another concert-goer quipped, “I suppose now Fritz Kreisler is going to start giving physics lectures.” Accounts of his abilities do differ.

Brian Foster’s interest in Einstein the musician transcends the man’s virtuosity, or lack thereof. Since 2005—the 100th anniversary of Einstein’s “miracle year,” during which he published his most influential papers—Foster has teamed up with British violinist Jack Liebeck and other classical musicians to present lectures and concerts on the role of music in Einstein’s life and work. Einstein’s devotion to Mozart may be of particular interest to historians of science. Foster describes Einstein’s tastes as “conservative”; he found Beethoven too “creative,” but Mozart, on the other hand, revealed to him a universal harmony he believed existed in the universe. As another author puts it:

Einstein relished Mozart, noting to a friend that it was as if the great Wolfgang Amadeus did not “create” his beautifully clear music at all, but simply discovered it already made. This perspective parallels, remarkably, Einstein’s views on the ultimate simplicity of nature and its explanation and statement via essentially simple mathematical expressions.

While the interpretation of Einstein as a “realist” has its detractors, his insistence on the beauty and simplicity of scientific theories is not in dispute. Foster points out above that part of Einstein’s legacy is his push for beauty, unification, and harmony in our physical understanding of reality, a push that Foster credits to the scientist’s musical mind.

Related Content:

Listen as Albert Einstein Reads ‘The Common Language of Science’ (1941)

James Joyce Plays the Guitar, 1915

Albert Einstein Expresses His Admiration for Mahatma Gandhi, in Letter and Audio

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him at @jdmagness

who is the author of this article?

Now we know why Einstein was a genius, he was a musician!

Jimmy Crimmins

Yeah, Einstein was great. At everything!

Josh Jones