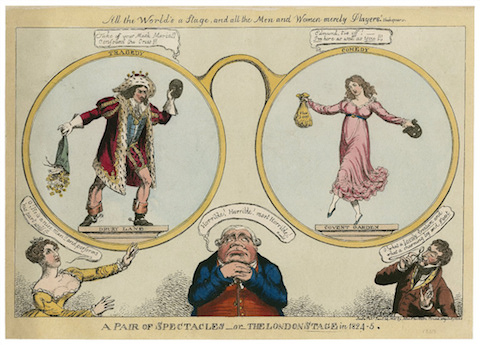

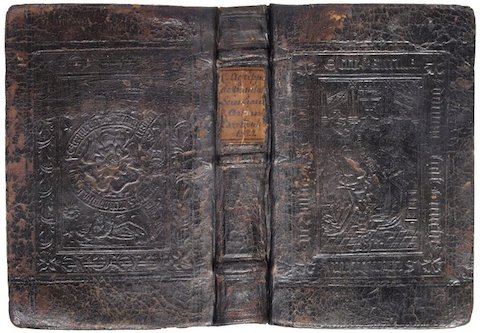

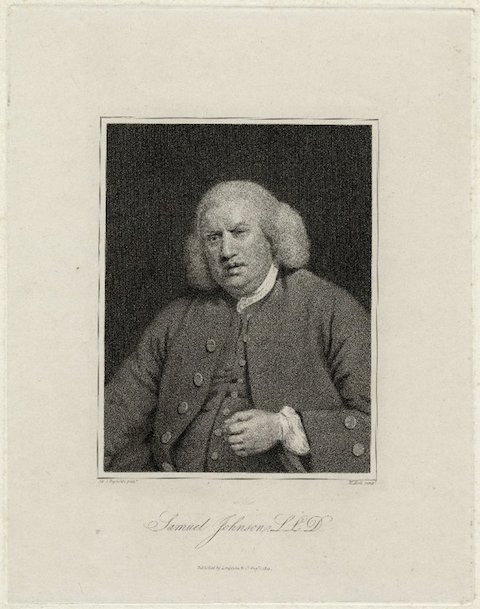

The BBC’s acclaimed podcast A History of the World in 100 Objects brought us just that: the story of human civilization as told through artifacts from the Egyptian Mummy of Hornedjitef to a Cretan statue of a Minoan Bull-leaper to a Korean roof tile to a Chinese solar-powered lamp. All those 100 items came from the formidable collection held by the British Museum, and any dedicated listener to that podcast will know the name of Neil MacGregor, the institution’s director. Now, MacGregor has returned with another series of historical audio explorations, one much more focused both temporally and geographically but no less deep than its predecessor. The ten-part Shakespeare’s Restless World “looks at the world through the eyes of Shakespeare’s audience by exploring objects from that turbulent period” — i.e., William Shakespeare’s life, which spanned the 1560s to the 1610s: a time of Venetian glass goblets, African sunken gold, chiming clocks, and horrific relics of execution.

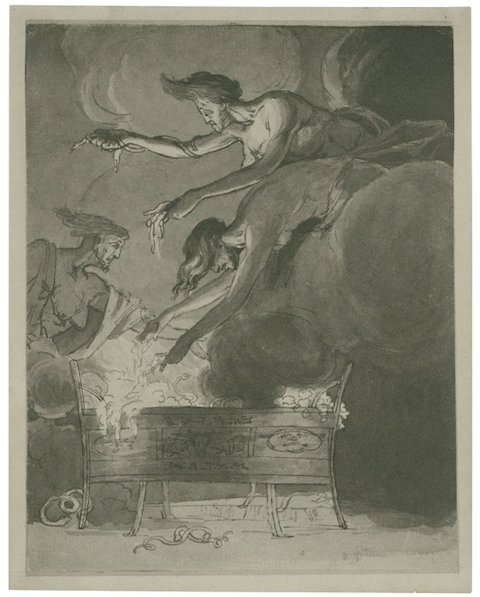

These treasures illuminate not only the English but the global affairs of Shakespeare’s day. The Bard lived during a time when murderers plotted against Elizabeth I and James I, England expelled its Moors, Great Britain struggled to unite itself, humanity gained an ever more precise grasp on the keeping of time, and even “civilized” nations got spooked and slaughtered their own. Just as the study of Shakespeare’s plays reveals a world balanced on the tipping point between the modern consciousness and the long, slow awakening that came before, the study of Shakespeare’s time reveals a world that both retains surprisingly vivid elements of its brutal past and has already begun incorporating surprisingly advanced elements of the future to come. Even if you don’t give a hoot about the literary merits of Richard III, Titus Andronicus, or The Merchant of Venice, these real-life stories of political intrigue, gruesome bloodshed, and, er, Venice will certainly hold your attention. You can start with the “tabloid history of Shakespeare’s England” in the first episode of Shakespeare’s Restless World above, then continue on either at the series’ site or on iTunes. And if you find yourself getting into the series, you can get MacGregor’s companion book, Shakespeare’s Restless World: Portrait of an Era.

via Metafilter

Related Content:

A History of the World in 100 Objects

Discover What Shakespeare’s Handwriting Looked Like, and How It Solved a Mystery of Authorship

Read All of Shakespeare’s Plays Free Online, Courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.