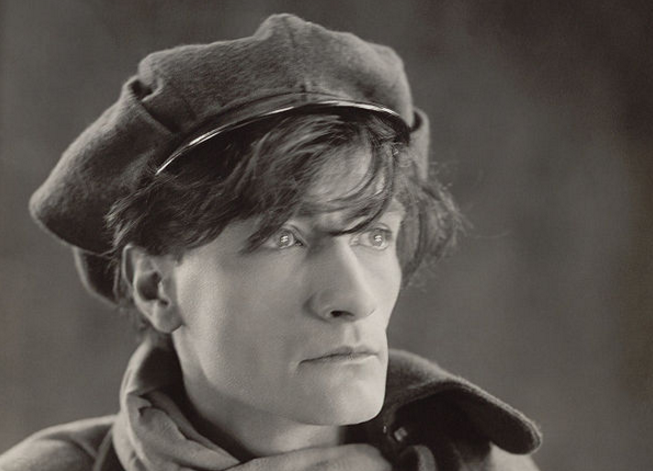

Think of radio plays, and you most likely think (or I most likely think) of the form’s American “golden age” in the first half of the 20th century. That time and place in radio drama conjures up a certain more or less defined set of sensibilities: rocketships hurtling toward unknown worlds, hard-bitten detectives sticking to their cases, suburban couples bickering about the behavior of their jalopy-driving children. By the 1950s, the conventions of radio plays had ossified too much even for old-time radio audiences. Who best to call to tear up the form and start it over again? Why, Samuel Beckett, of course.

“In 1955 the BBC, intrigued by the international attention being given to the Paris production of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (see a version here), invited the author to write a radio play,” says the short history provided in the program of the Beckett festival of Radio Plays. Though hesitant, Beckett nevertheless wrote the following to a friend: “Never thought about radio play technique but in the dead of t’other night got a nice gruesome idea full of cartwheels and dragging of feet and puffing and panting which may or may not lead to something.’ ” That “gruesome idea” led, according to the program, not just to Beckett’s 1956 radio-play debut All That Fall, but four more to follow over the next twenty years.

At the top of the post, you can listen to that first 70-minute sonic tale of an old, obese Irish housewife, the blind husband she meets at the train station as a birthday surprise, and all the children, eccentrics, weather, and thoroughly Beckettian dialogue that give texture to the death-obsessed journeys from home and back to it. All That Fall received critical acclaim, but the later radio play just above, the next year’s 45-minute Embers, found a more mixed reception — to the delight, one imagines, of most Beckett fans, who tend to prefer the divisive stuff to an agreed-upon canon anyway.

Built out of two monologues, a dialogue, and the sounds of the sea, Embers’ “rather ragged” script (in the words of Beckett himself, who later took the blame for the“too difficult” text) presents us with an inarticulate protagonist who leaves us with many more questions than answers. But just as in the work acknowledged as Beckett’s best, the questions we come away with send us in more interesting directions than do the answers provided in mainstream radio drama — or in mainstream anything else, for that matter. And amid all this writing for tape rather than stage, what noted work did he come with in 1958 for the stage? Why, Krapp’s Last Tape, of course.

Samuel Beckett’s radio plays available online:

- All That Fall (1957)

- Embers (1959)

- Words and Music (1962)

- Cascando (1963)

Related Content:

Samuel Beckett Directs His Absurdist Play Waiting for Godot (1985)

Monsterpiece Theater Presents Waiting for Elmo, Calls BS on Samuel Beckett

Rare Audio: Samuel Beckett Reads Two Poems From His Novel Watt

Colin Marshall writes on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.