In 1935, a 19-year-old Orson Welles—just becoming well-known as a radio actor—found himself part of the Federal Theatre Project, a New Deal program started to help struggling writers, actors, directors, and theater workers. Hired by John Houseman, then director of New York’s Negro Theatre Unit, Welles threw himself into the project, even investing his own earnings from his radio work to speed productions along and make them more professional. He would later tell Peter Bogdanovich, “Roosevelt once said that I was the only operator in history who ever illegally siphoned money into a Washington project.”

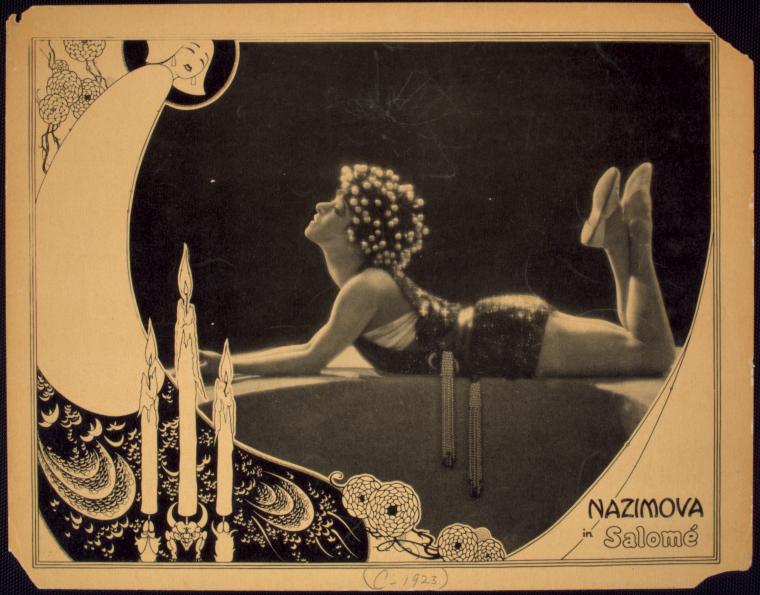

For his first play, Welles adapted Shakespeare’s Macbeth, setting it on the island of Haiti under post-revolutionary ruler King Henri Christophe. Instead of the Scottish witchcraft of the original, Welles’ production featured Haitian vodou rituals, and it thus acquired the name “Voodoo Macbeth.”

You can see four minutes of the production in the film above. Despite the change of setting, a voiceover announcer tells us, “the spirit of Macbeth and every line of the play has remained intact.”

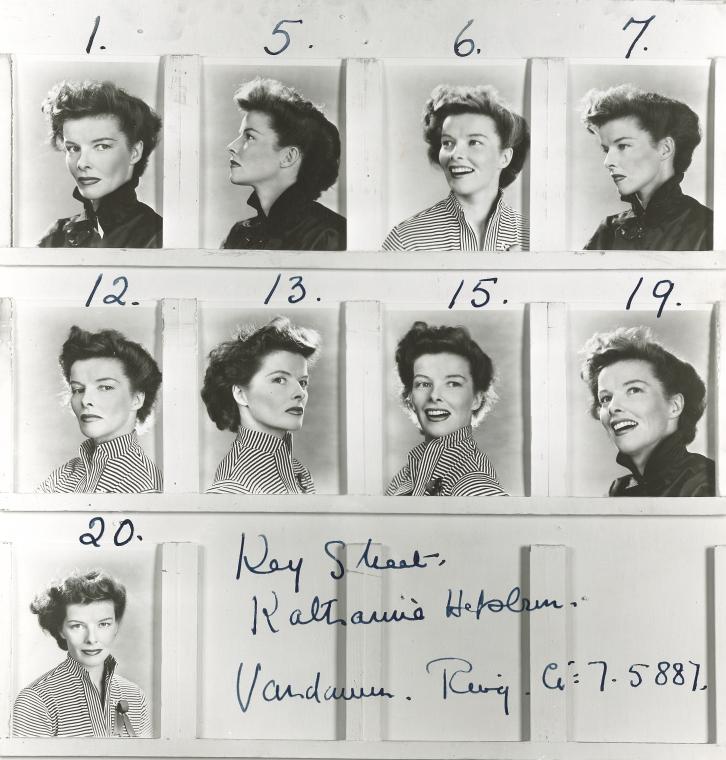

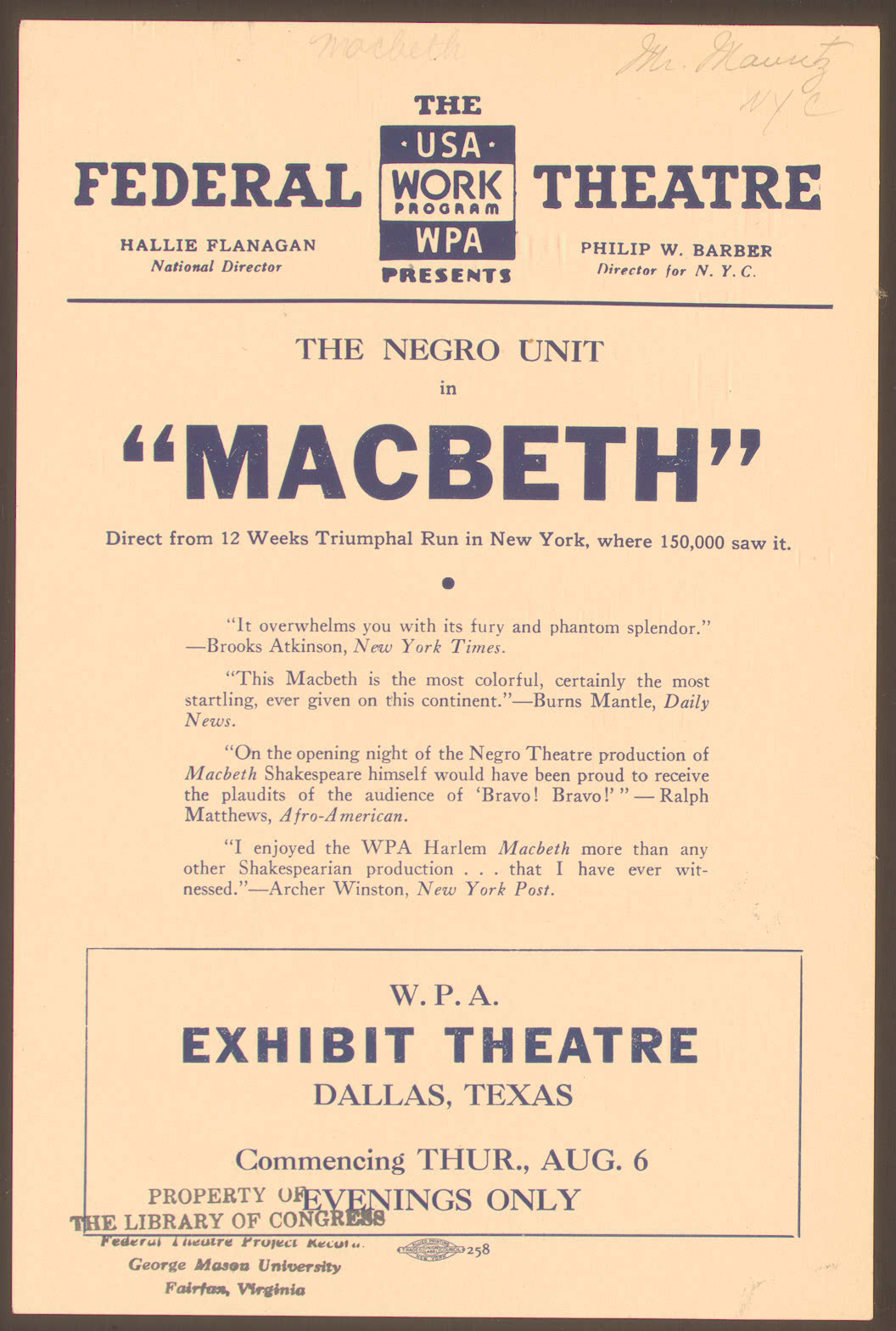

The play debuted in 1936 at Harlem’s Lafayette Theater and was performed for segregated audiences. It was so popular that it exceeded its initial run, then toured the country, spending two weeks in Dallas at the Texas Centennial Exposition (see a playbill above). Welles, at 20 years of age, was hailed as a prodigy. The adaptation, writes the Digital Public Library of America, “brought magical realism and aspects of Haitian culture to the production.”

The play included drummers who played and sang chants from voodoo ceremonies. Welles reimagined the witches from the original Macbeth as voodoo priestesses. Costumes reflected fashion from Haiti’s nineteenth-century colonial period.

As with so many of Welles’ theater experiments, critical opinion divided sharply. Some, including the Harlem Communists, saw the play as racist comedy. Many others “felt that Welles’ casting of an entire company of African-American actors allowed these actors to show their talent and tenacity during performances in front of segregated audiences.”

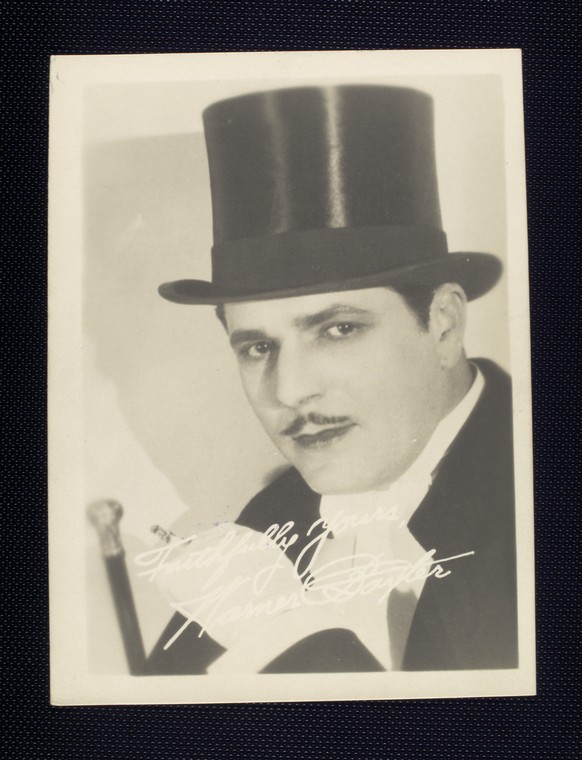

The play employed 150 actors, including boxer and successful film actor Canada Lee as Banquo (above), and “raised contemporary social issues that for some drew uncomfortable attention to national problems.” (Wikipedia has a full cast list and several production stills.)

All footage of the production was thought lost for several years, until the four minutes at the top were discovered in the short film above, “We Work Again.” Produced by Alfred Edgar Smith—a civil rights activist and onetime member of F.D.R.‘s so-called “Black Cabinet”—this film details in optimistic tones the WPA’s success in creating jobs for unemployed African-Americans. Smith worked, writes The New York Times, “to ban differential pay rates and to hire black case workers in the South,” and he made “We Work Again” as one of many “studies on how blacks fared under relief programs.” His efforts, of course, have their own historical significance, but we can also thank Smith for preserving the only surviving sound and moving image of Welles’ first major theatrical production. “The ‘Voodoo’ Macbeth,” writes Shakespeare scholar Susan McCloskey, is notable as “the first black professional production of Shakespeare, an important critical and commercial success for the Federal Theatre, and an appropriately dazzling debut for its twenty-year-old director.”

Related Content:

Orson Welles’ Radio Performances of 10 Shakespeare Plays

Orson Welles Turns Heart of Darkness Into a Radio Drama, and Almost His First Great Film

The Hearts of Age: Orson Welles’ Surrealist First Film (1934)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness