“Among the founders of religions,” writes Walpola Rahula in his book What the Buddha Taught, “the Buddha…was the only teacher who did not claim to be other than a human being, pure and simple. […] He attributed all his realization, attainment and achievements to human endeavor and human intelligence.” Rahula’s interpretation of Buddhism is only one of a great many, of course. In some traditions, the Buddha is miraculous and more or less divine. But this quote sums up why the generally non-theistic system of Eastern thought is often called a psychology or philosophy rather than a religion. With the video above, Alain de Botton—whose School of Life has recently brought us a survey of Western philosophers—begins his introduction to Eastern thought with Buddhism. The Buddha’s story, de Botton says, “is a story about confronting suffering.”

Born the son of a wealthy Indian king and destined for greatness by a prophecy—or so the story goes—Siddhartha Gautama, the future Buddha, discovered human suffering during brief excursions from his palace. Appalled and disturbed by sickness, aging, and death, the Buddha left his luxurious life (and his wife and son) and practiced many rituals and austerities before finding his own path to enlightenment and Nirvana—the extinguishing of desire.

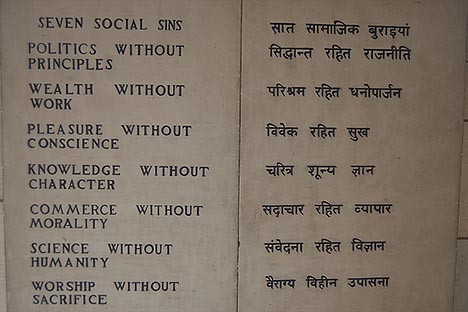

One fruit of his realization is the doctrine of “the Middle Way,” a mediation between extremes that one source compares to Aristotle’s golden mean, “whereby ‘every virtue is a mean between two extremes, each of which is a vice.’” The Buddha’s enlightened understanding of the essential continuity of life gave him compassion for all living beings; of the thousands of sutras, or sayings, attributed to him, his teaching can be concisely summed up in what he called “the Four Noble Truths,” the acknowledgement, cause, and remedy of inevitable pain and discontent.

Most of what de Botton does in his introduction to the Buddha will be familiar to anyone who has taken a comparative religions class. But true to his task of approaching Buddhism philosophically, he avoids Buddhist metaphysics, cosmology, and questions of rebirth, instead interpreting the Buddha’s teachings as a kind of Eastern Aristotelian ethics: “We must change our outlook (not our circumstances). We are unhappy not because we don’t have enough money, love, or status, but because we’re greedy, vain, and insecure. By reorienting our minds we can become content. By reorienting our behavior, and adopting what we now term a ‘mindful’ attitude, we can also become better people.”

While Buddhist scholars and sages would argue that enlightenment entails a great deal more than self-improvement, the summation suits the purposes of de Botton’s School of Life—to help people “live wisely and well.” These videos—like his others, animated by Mad Adam films with Monty Pythonesque whimsy—distill Eastern thought into fun, bite-sized nuggets. Just above, we have a short introduction to the Chinese sage Lao Tzu, purported author of the Tao Te Ching, the founding text of Daoism. Whereas de Botton seems to take the Buddha’s story more or less for granted, he admits above that Lao Tzu may well be a mythical character, “like Homer,” and that the Tao is likely the work “of many authors over time.”

Daoism is often intertwined with Buddhism and Confucianism, but its own particular philosophy is distinct from either tradition. At the heart of Daoism is wu wei, which translates to “non-action” or “non-doing,” a mode of being that seeks harmony with the rhythms of nature and a ceasing of preoccupation and ambition. Another “key point” of Lao Tzu’s instructions for realizing the “Tao,” or “the way,” is getting “in touch with our real selves,” something we can only accomplish through receptivity to nature—our own and that outside us—and through freedom from distraction, a most difficult demand for technology-obsessed 21st century people.

The third video in de Botton’s series surveys a Japanese Zen Buddhist sage and contrasts him with Western philosophers, who generally write long, obscure books and cloister themselves in lecture halls and offices. In the Zen tradition, de Botton says, “philosophers write poems, rake gravel, go on pilgrimages, practice archery, write aphorisms on scrolls, chant, and in the case of one of the very greatest Zen thinkers, Sen no Rikyu, teach people how to drink tea in consoling and therapeutic ways.” Born in 1522 near Osaka, Rikyu reformed and refined the chanoyu, the Japanese tea ceremony, into a rigorous but elegant meditative practice. Rikyu coined the term wabi-sabi, a compound of words for “satisfaction with simplicity and austerity” and “appreciation for the imperfect.” Wabi-sabi offers not only the foundation for a way of life, but also for a way of design and architecture, and its practice informs a great deal of traditional Japanese aesthetics.

Like Lao Tzu, Rikyu intended his practices to help people reconnect with the simplicity and harmony of nature, as well as with each other, inspiring mutual respect free of status-consciousness and competition. Rikyu’s wabi-sabi philosophy is premised on Zen’s understanding of the impermanence, imperfection, and incompleteness of everything. Therefore he eschewed the trappings of luxury and preferred worn and humble objects in his ceremonial instructions. Whether we call Rikyu’s practices religious or philosophical seems to make little difference. In the case of the three thinkers profiled here, the distinction may be meaningless and introduce Western conceptual divisions that only obscure the meaning of Buddhism, Daoism, and Japanese Zen. When it comes to the latter, another Western interpreter, Alan Watts, once delivered an excellent talk called “The Religion of No Religion” that helps to explain practices like Rikyu’s chanoyu.

All of the videos here are part of the School of Life’s “Curriculum.” Visit de Botton’s Youtube channel for more, and for short videos offering advice on everything from anxiety to relationships to “the dangers of the internet.”

Related Content:

Alain de Botton’s School of Life Presents Animated Introductions to Heidegger, The Stoics & Epicurus

What Are Literature, Philosophy & History For? Alain de Botton Explains with Monty Python-Style Videos

A Guide to Happiness: Alain de Botton Shows How Six Great Philosophers Can Change Your Life

Alain de Botton Shows How Art Can Answer Life’s Big Questions in Art as Therapy

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness