The holiday film release season has now passed, having issued only one real blockbuster, which is the return of Wonder Woman. This week’s Pretty Much Pop likewise offers a returning hero: Our college-going guest from ep. 33 on heroine journeys has now grown into a grad student in comics history, and she brings her deep WW knowledge to consider with your hosts Erica Spyres, Mark Linsenmayer, and Brian Hirt.

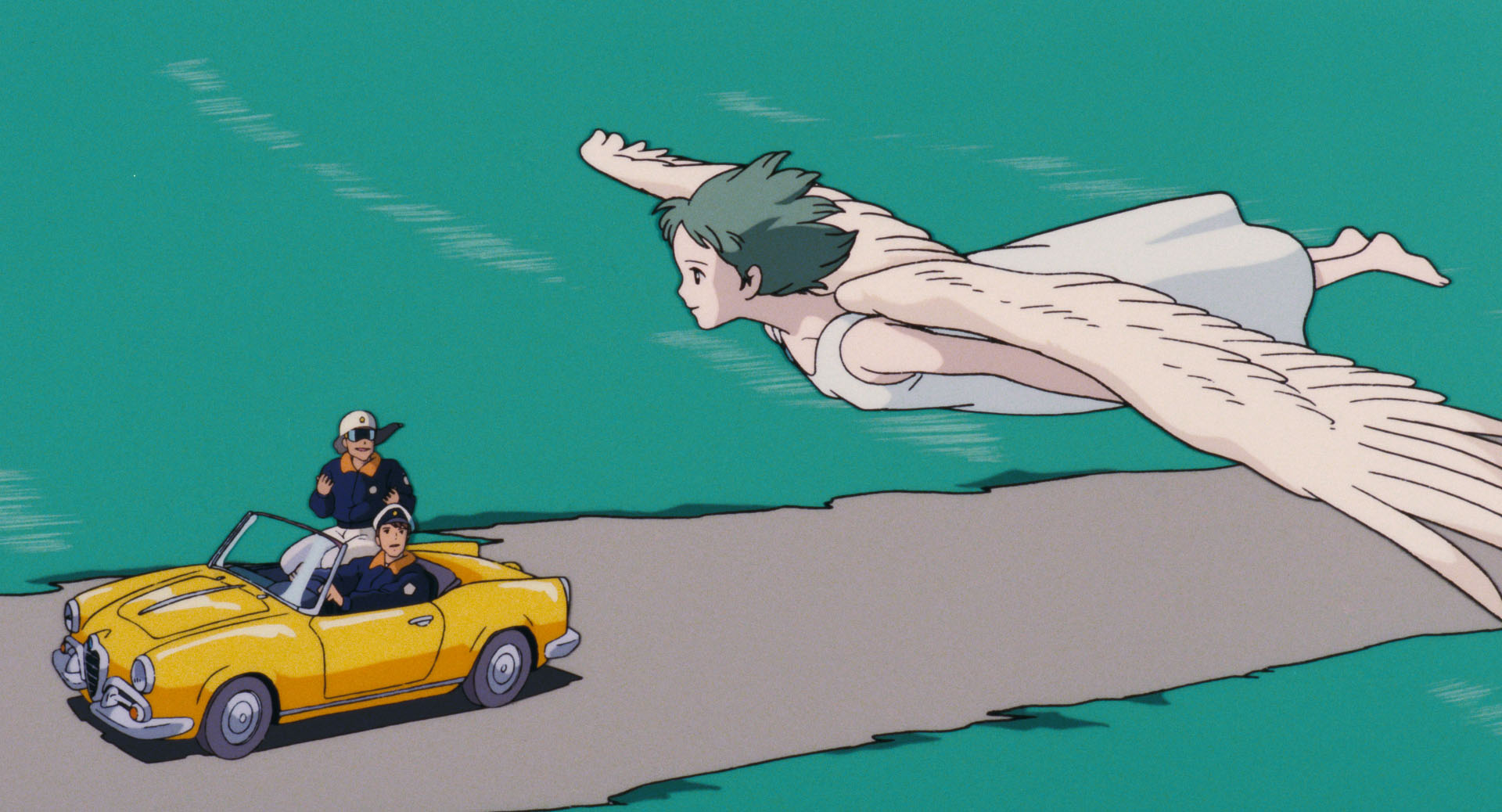

Part of the relevant context is the 2017 biopic Professor Marston and the Wonder Women, which revealed the unorthodox views of WW’s creator, and so of course this shows up in how WW judges us: She’s not just a Captain America-style patriot, but a foreigner who in the new film compassionately condemns our 80s greed and dishonesty. But do the themes actually make sense? And what’s with having her love interest return from the dead, hijacking another man’s body with no acknowledgment that that’s very skeevy?

Also, how does the depiction of WW’s homeland compare to other feminist utopias like Herland and “Sultana’s Dream”? Does it matter that WW was created by and initially aimed primarily at males? We learn a little about the post-Marston WW (who couldn’t join the Justice League, which was for boys only!) and talk about the ’70s TV show, the outfits, the villains, and WW in love.

Here are a few supplementary articles:

- “The Surprising Origin Story of Wonder Woman” by Jill Lepore

- “Does Wonder Woman 1984 Have a Steve Trevor Problem?” by Sarah El-Mahmoud

- “The Warped Morality of ‘Wonder Woman 1984’ ” by Dani Di Placido

- “How Wonder Woman 1984 Reboots the DC Hero’s Forgotten Superpower” by Eric Francisco

- “How ‘Wonder Woman 1984’ Villain Maxwell Lord Stays True to the Comics” by Graeme McMillan

- And from our former guest, Noah Berlatsky: “HBO Max’s ‘Wonder Woman 1984’ Stars a Trump‑y Villain, Gal Gadot’s Charm and a Garbled Message”

Hear more of this podcast at prettymuchpop.com. This episode includes bonus discussion you can access by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network.

Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts.