Mushrooms have quietly become superstars of the global stage.

Sure, not everyone likes them on pizza, but who cares?

In the 21st-century, they are hailed as role models and potential planet savers (not to mention a wildly popular design motif…)

Time-lapse cinematography pioneer Louie Schwartzberg’s critically acclaimed documentary, Fantastic Fungi, has made experts of us all.

Go back a century, and such knowledge was much harder won, requiring time, patience, and proximity to field or forest.

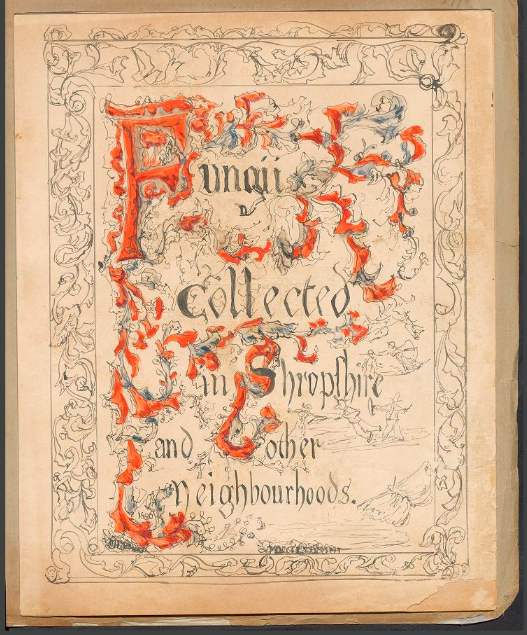

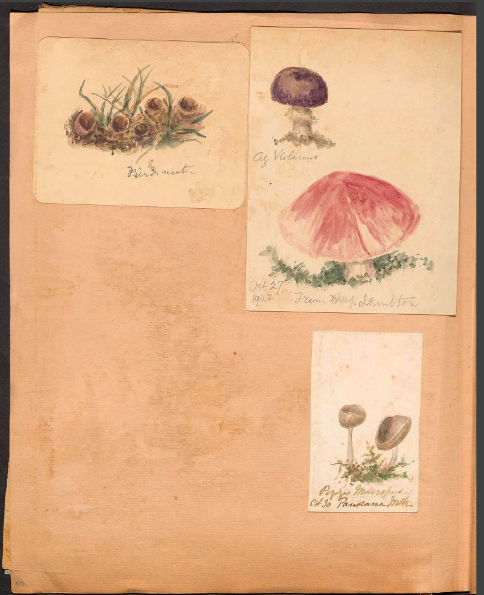

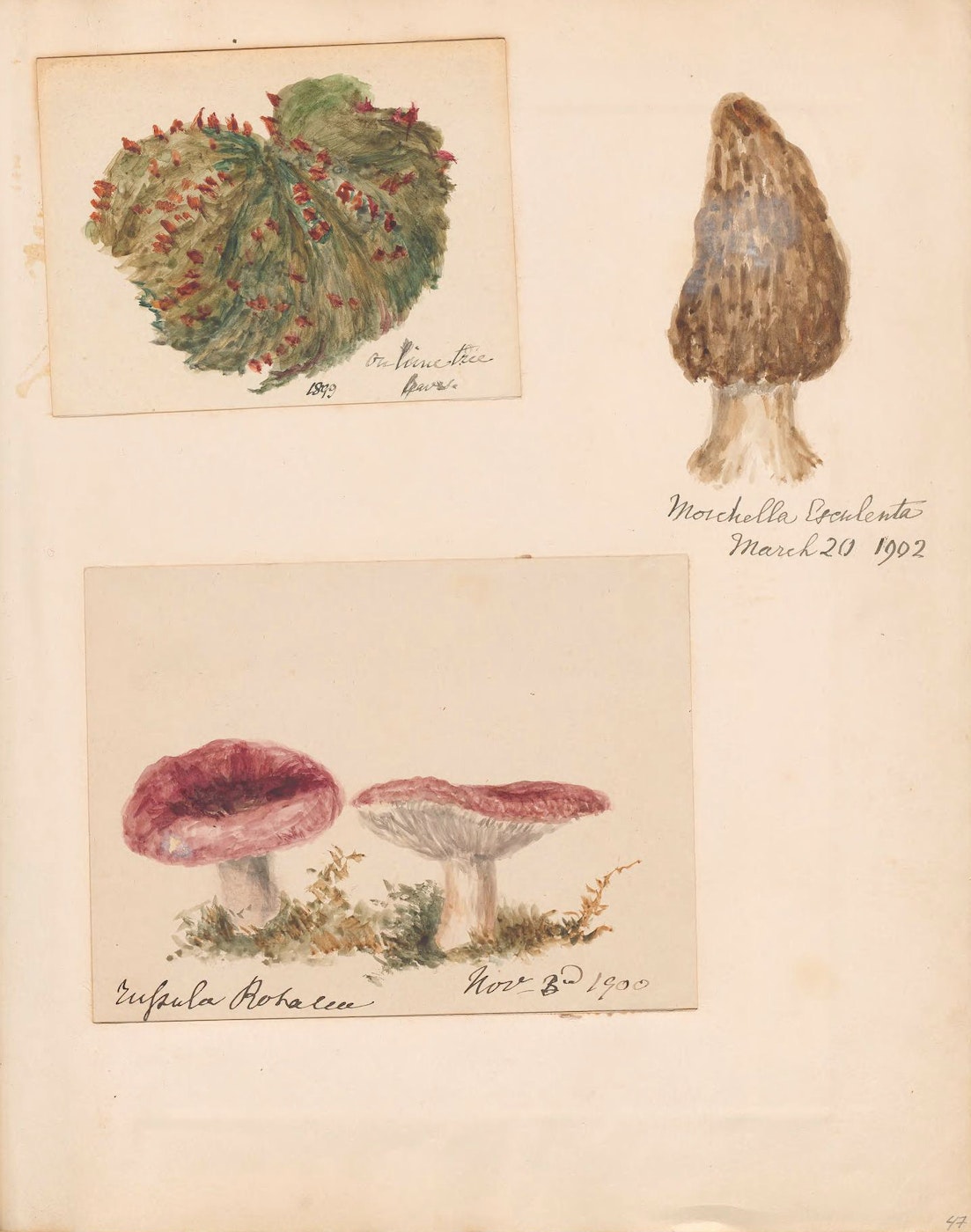

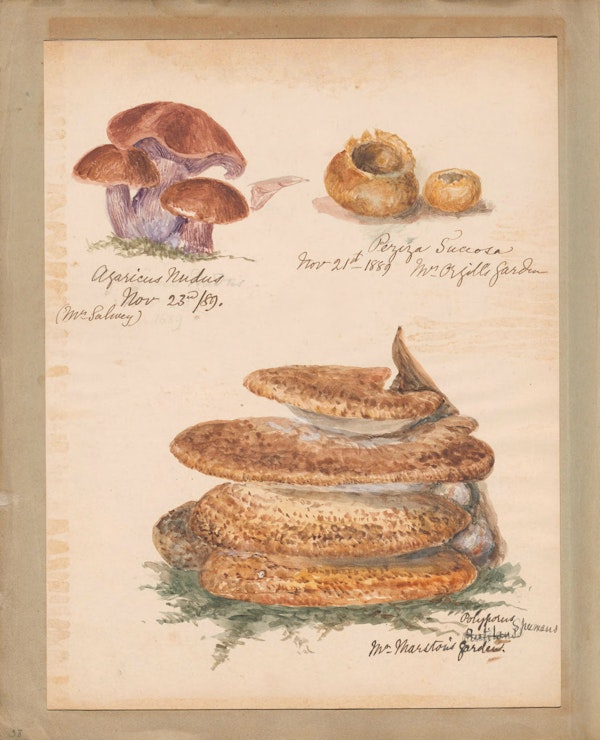

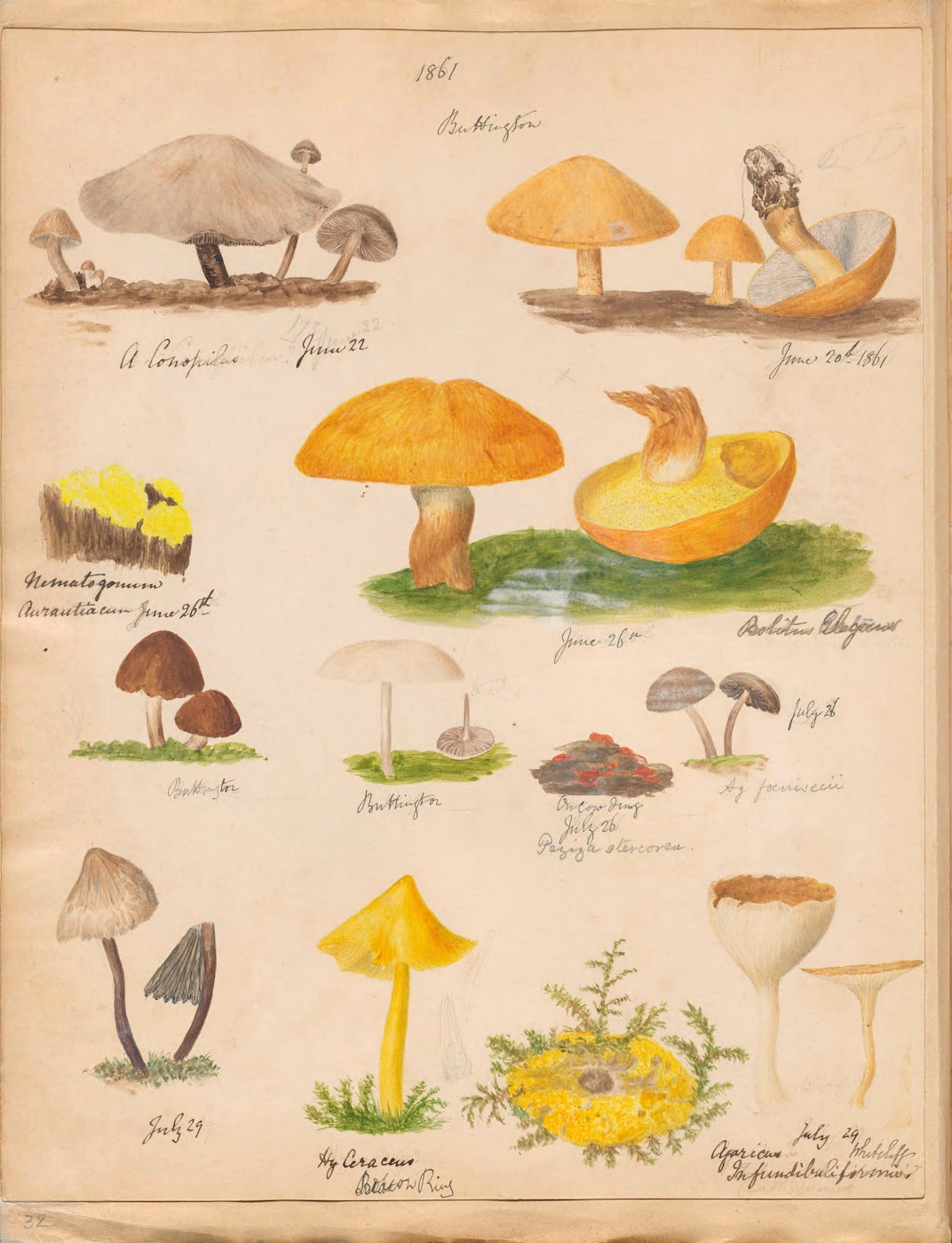

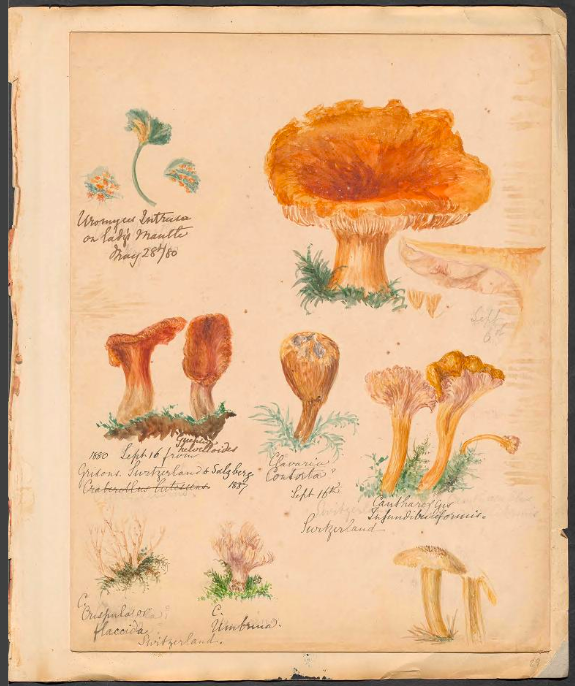

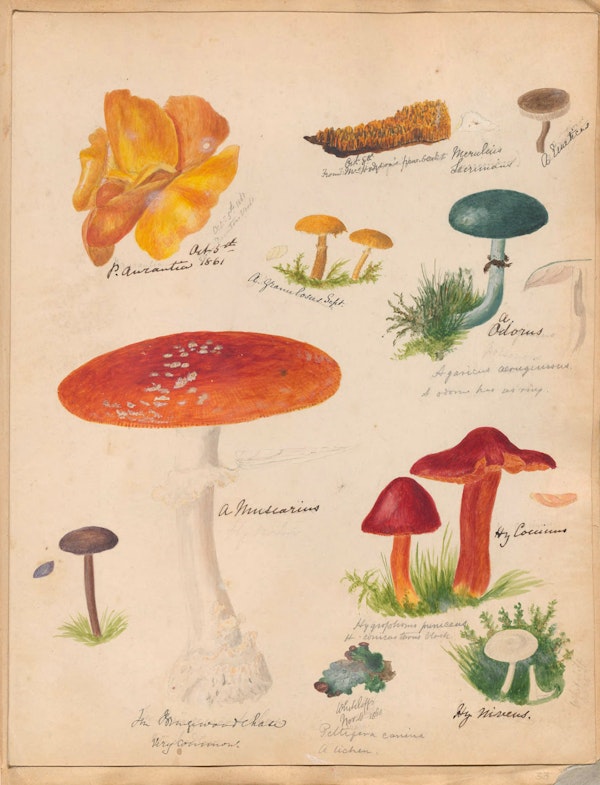

Witness Fungi collected in Shropshire and other neighborhoods, a handbound, hand-illustrated 3‑volume collection by one Miss M. F. Lewis, of Ludlow, England.

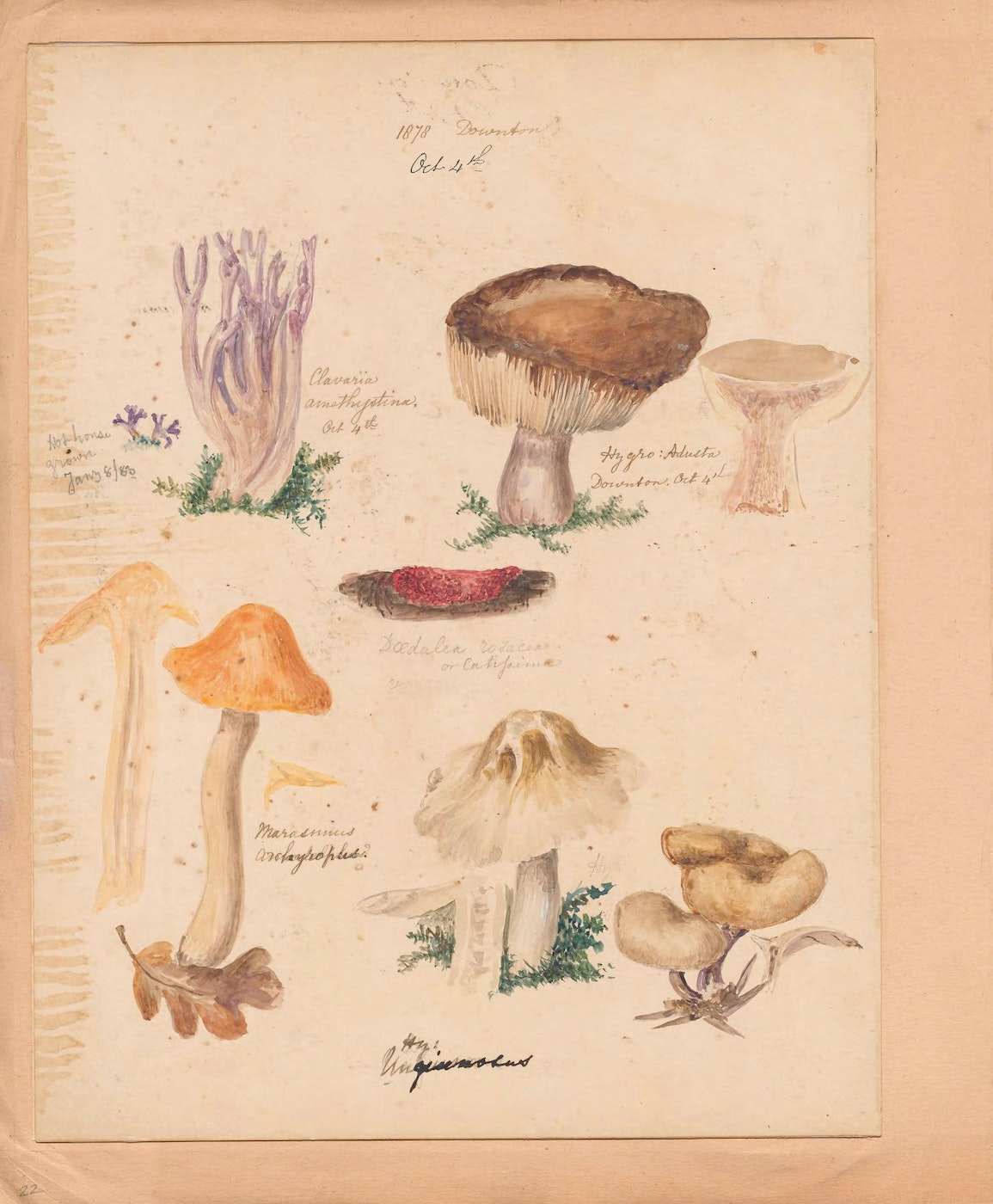

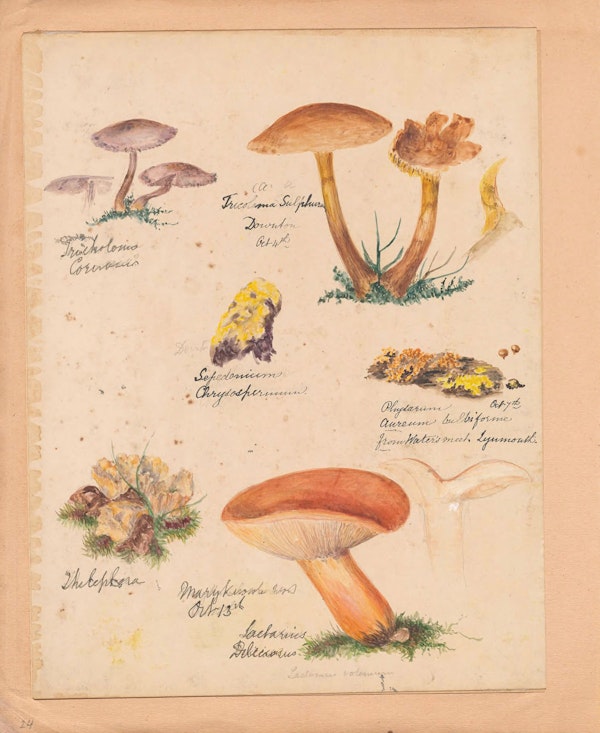

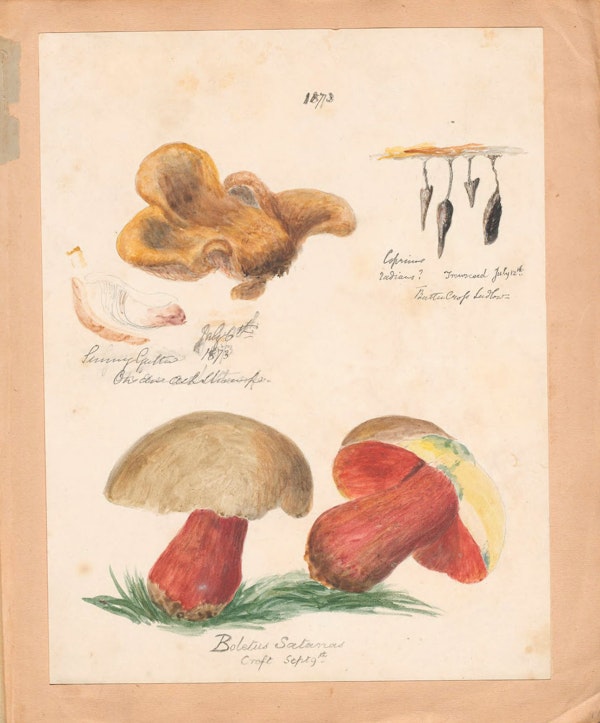

Miss Lewis, a talented artist with an obvious passion for mycology spent over 40 years painstakingly documenting the specimens she ran across in England’s West Midlands region.

Each drawing or watercolor is identified in Miss Lewis’ hand by its subject’s scientific name. The location in which it was found is dutifully noted, as is the date.

The hundreds of species she captured with pen and brush between 1860 and 1902 definitely constitute a life’s work, and also an unpublished one.

Cornell University’s Mann Library, where the only copy of this precious record is housed, has managed to truffle up but a single reference to Miss Lewis’ scientific mycological contribution.

English botanist William Phillips, writing in an 1880 issue of the Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, noted that he been “permitted to look over [a work] of very much excellence executed by Miss M. F. Lewis, of Ludlow”, adding that “several rare species [of fungi] are very artistically represented.“

The historical significance of Miss Lewis’ work extends beyond the fungal realm.

As Sage writes in Missing Misses in Mycology, a post on the Mann Library’s Tumblr celebrating Miss Lewis and her contemporary, English mycologist and illustrator, Sarah Price, women’s work was often omitted from the official scientific record:

While we’re now seeing considerable effort to rectify the record, the discovery of untold stories to fill in the blanks can be tricky business. It’s not that the stories never happened — the field of botany, for one, is replete with some pretty spectacular evidence of women’s (often unacknowledged) engagement with scientific inquiry, embodied in the detailed illustrations that captured the insights of observations from the natural world. But the published historical record is often woefully scant when it comes to closer detail on the lives and careers of the women who have helped carry modern science forward.

We may never learn anything more about the particulars of Miss Lewis’ training or personal circumstances, but the care she took to preserve her own work turned out to be a great gift for future generations.

Leaf through all three volumes of Miss M.F. Lewis’ Fungi collected in Shropshire and other neighborhoods on the Internet Archive:

Related Content

John Cage Had a Surprising Mushroom Obsession (Which Began with His Poverty in the Depression)

The Beautifully Illustrated Atlas of Mushrooms: Edible, Suspect and Poisonous (1827)

Algerian Cave Paintings Suggest Humans Did Magic Mushrooms 9,000 Years Ago

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.