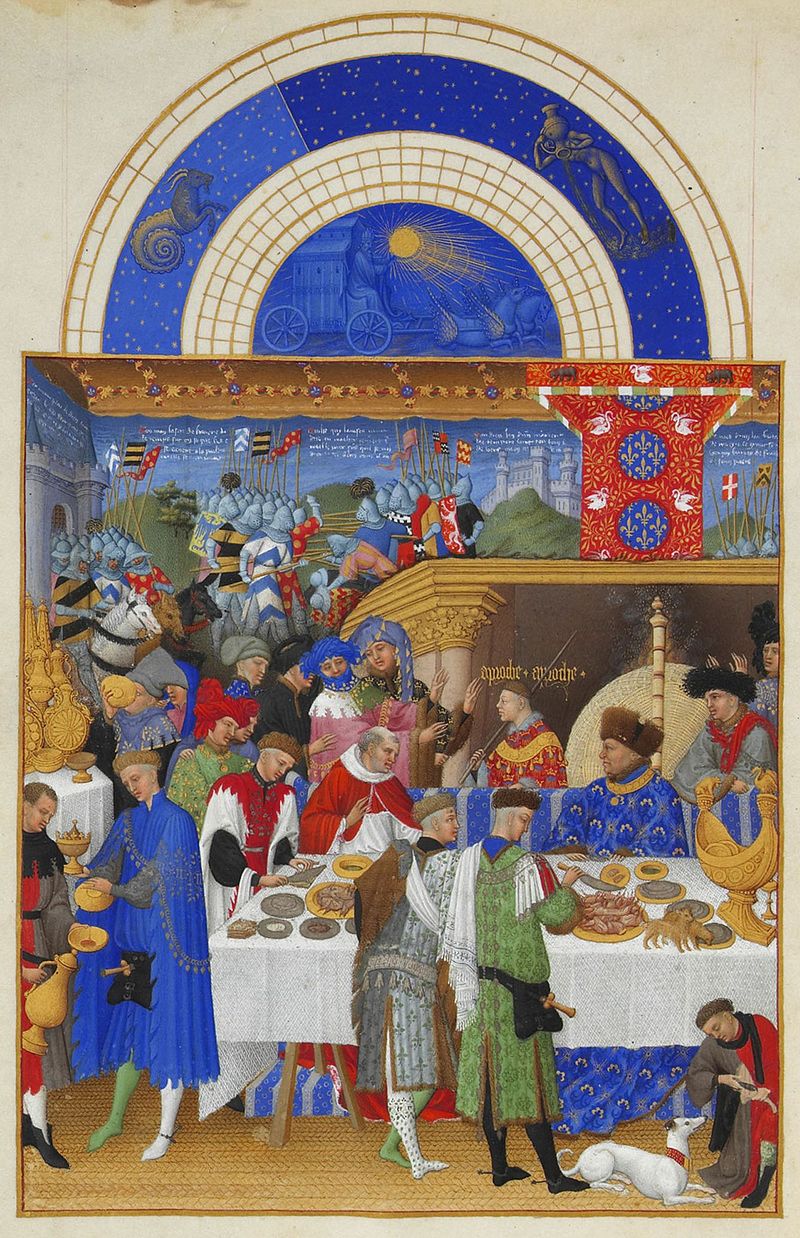

Today we think of the Renaissance as one of those periods when everything changed, and if the best-known artifacts of the time are anything to go by, nothing changed quite so much as art. This is reflected in obvious aesthetic differences between the works of the Renaissance and those created before, as well as in less obvious technical ones. Egg yolk-based tempera paints, for example, had been in use since the time of the ancient Egyptians, but in the fifteenth century they were replaced by oil paints. When chemical analysis of the work of certain Renaissance masters revealed traces of egg, they were assumed to be the result of chance contamination.

Now, thanks to a recent study led by chemical engineer Ophélie Ranquet of the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, we have reason to believe that painters like Botticelli and Leonardo kept eggs in the mix deliberately. Oil replaced tempera because “it creates more vivid colors and smoother color transitions,” writes Smithsonian.com’s Teresa Nowakowski.

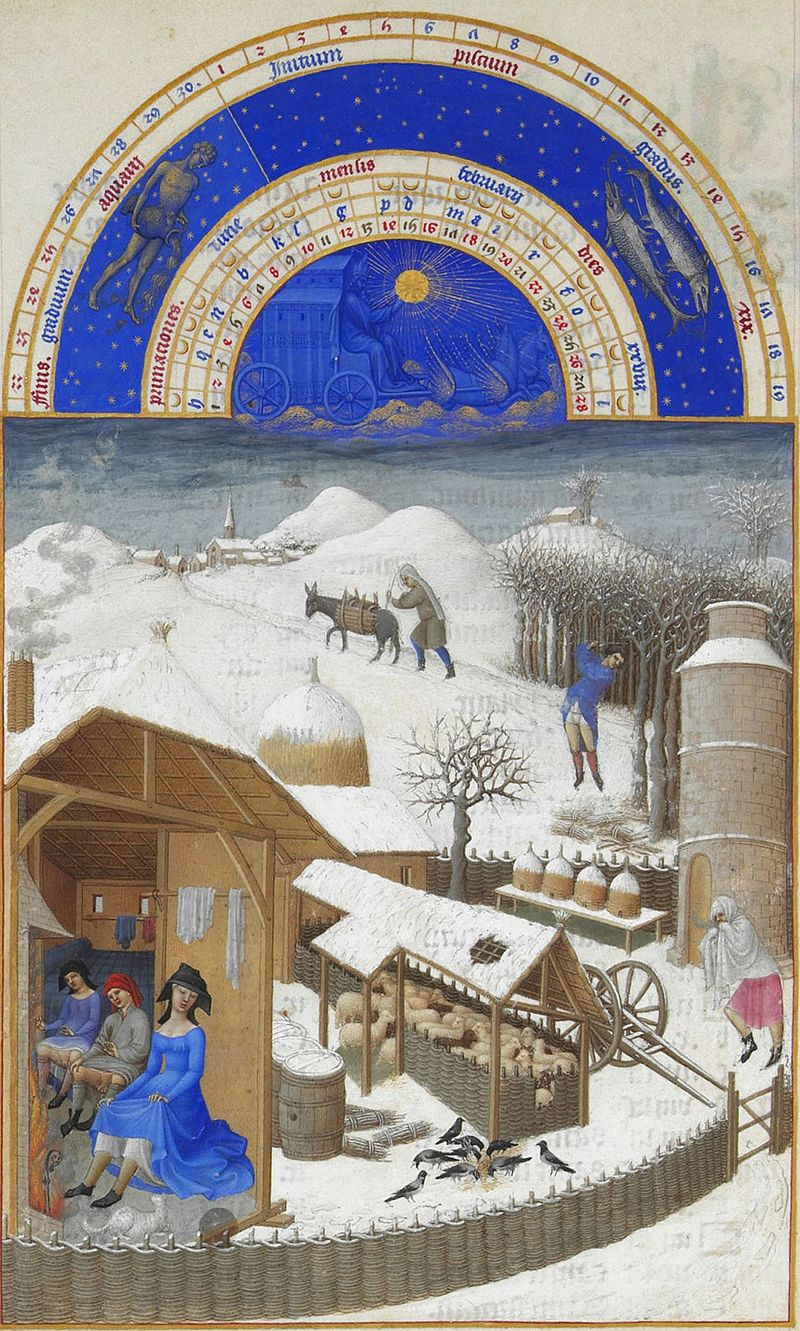

“It also dries slowly, so it can be used for longer after the initial preparation.” But “the colors darken more easily over time, and the paint is more susceptible to damage from light exposure. It also has a tendency to wrinkle as it dries,” visible in Leonardo’s Madonna of the Carnation below.

Putting in a bit of egg yolk may have been a way of using oil’s advantages while minimizing its disadvantages. Ranquet and her collaborators tested this idea by doing it themselves, re-creating two pigments used during the Renaissance, both with egg and without. “In the mayolike blend” produced by the former method, writes ScienceNews’ Jude Coleman, “the yolk created sturdy links between pigment particles, resulting in stiffer paint. Such consistency would have been ideal for techniques like impasto, a raised, thick style that adds texture to art. Egg additions also could have reduced wrinkling by creating a firmer paint consistency,” though the paint itself would take longer to dry.

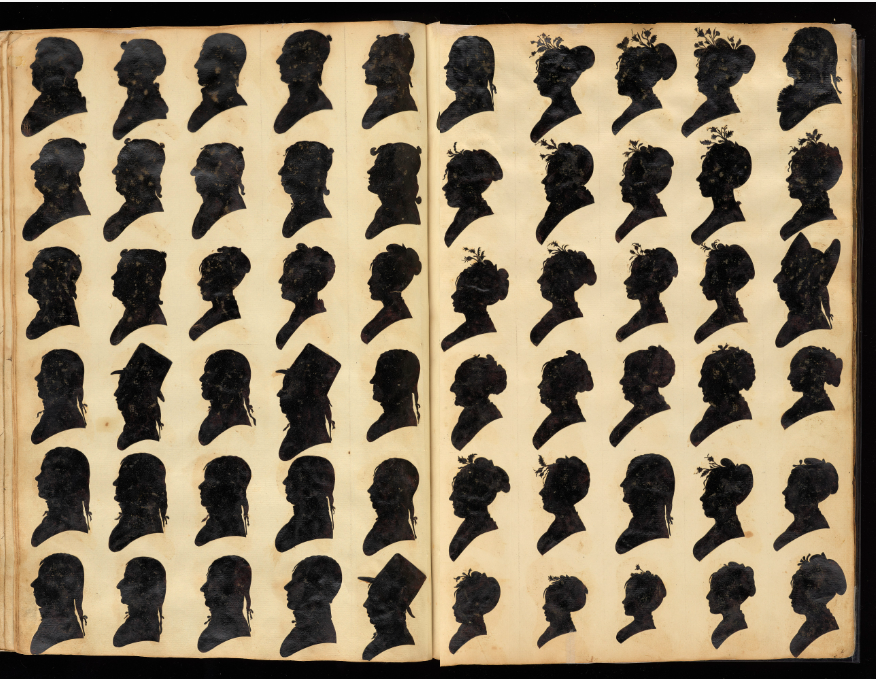

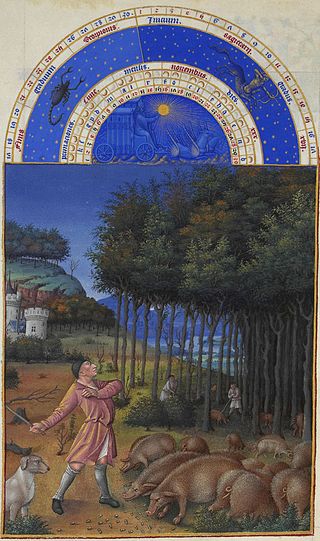

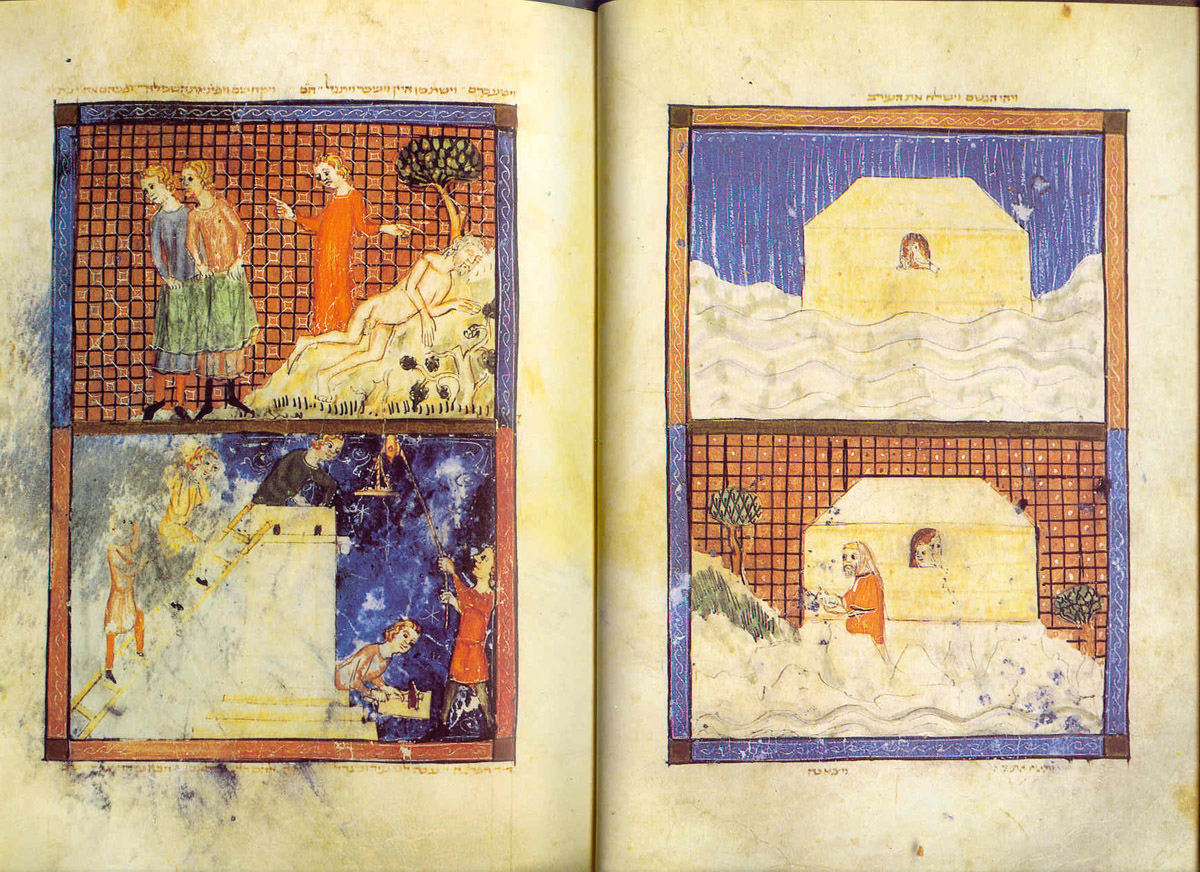

In practice, Renaissance painters seem to have experimented with different proportions of oil and egg, and so discovered that each had its own strengths for rendering different elements of an image. Hyperallergic’s Taylor Michael writes that in The Lamentation Over the Dead Christ, seen up top, “Botticelli painted Christ, Mary Magdalene, and the Virgin, among others, with tempera, and the background stone and foregrounding grass with oil.” Thanks to the oxidization-slowing effects of phospholipids and antioxidants in the yolk — as scientific research has since proven — they’ve all come through the past five centuries looking hardly worse for wear.

Related content:

How Caravaggio Painted: A Re-Creation of the Great Master’s Process

A 900-Page Pre-Pantone Guide to Color from 1692: A Complete High-Resolution Digital Scan

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.