Most major world cities now boast far-reaching and convenient subway systems, but London will always have the original from which all the rest descend. It will also, arguably, always have, in the Tube, by far the most iconic. The Metropolitan Railway, the first underground train line to open in London and thus the first in the world, entered service in 1863. Other lines followed, run by several different companies, until, says Make Big Plans, all the operators “agreed on a joint marketing strategy in 1908 that featured the now familiar logo with a red disk and the word ‘Underground.’ ”

But by 1913, writes the BBC’s Emma Jane Kirby, “passengers are moaning about unpunctuality, about overcrowding, about confusion and dirt. The Tube, crammed on workdays (some 400,000 people now work in the heart of the city) is virtually empty at weekends and holidays and the company is fast losing money and public support. What we need, thinks [London Underground commercial director Frank] Pick, is stronger branding.” In addition to the immortal logo, he wanted “some eye-catching posters, distinct from general advertisement bills, that will make Londoners of all social classes proud to journey around their city and visit its attractions.”

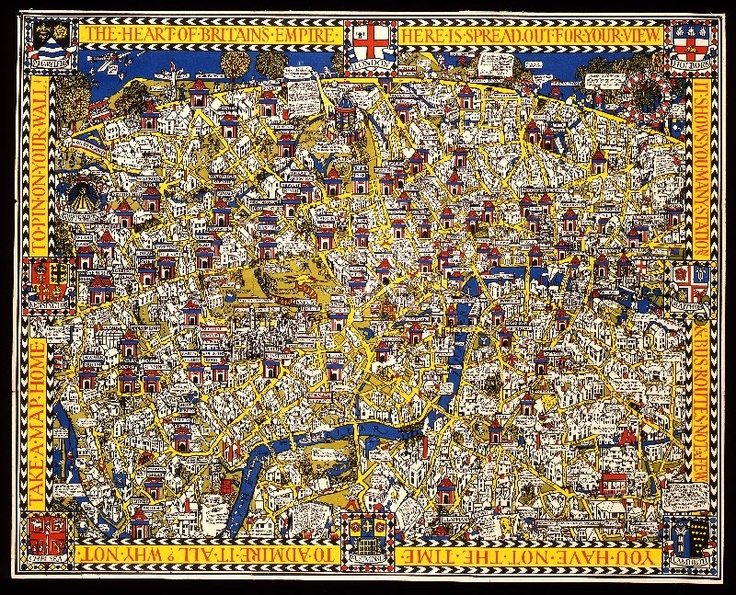

But a transit system, even the formidable London Underground, is only as good as its maps. Eric Gill, the Arts and Crafts movement luminary who helped design the Tube’s typeface, asked his architect-cartographer-graphic designer brother MacDonald to come up with an eye-catching one. In the result, writes the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America’s Elisabeth Burdon, “all the attractions and amenities of London are laid before the viewer in a manner which is both visually exciting and yet within a comprehensible structure; the city is presented in the manner of a medieval walled town, the curved horizon recalling the medieval world map’s enclosing circle, all bounded by a decorative border in which coats of arms evoke a sense of stability and tradition.”

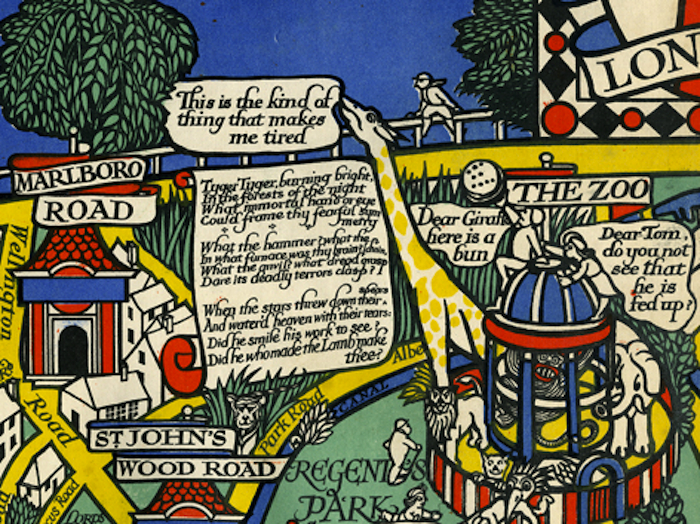

Apart from its degree of historical astuteness and cartographical soundness, Gill’s “Wonderground Map,” as Londoners came to call it, contained enough humor that some of the passengers who consulted it missed their trains due to sheer amusement. Kirby points out that, “on the Harrow Road, a farm worker tilling the soil cries ‘Harrowing work, this!’ an exclamation which is countered by the query ‘What is work, is it a herb?’ delivered by an effete gentleman nearby.” A sign placed at the map’s eastern edge points the way to “Victoria Park, Wanstead Flats, Harwich, Russia and other villages,” while “at Regent’s Park Zoo a prehistoric-looking bird eats a child through the bars of its cage as the child laments, ‘and I promised mother I’d be home for tea by five!’ ”

The Wonderground Map attained such popularity that it became the first London Underground poster sold commercially for homes and offices, and remains on sale more than a century later. You can view the whole thing online, and in zoomable detail, here; if you’d like a printable version, you can find one here. The history of London now credits it as having effectively “saved” the Tube, whose reputation for dysfunction and discomfort had reached a critical point. Newer subway systems elsewhere may have since made great technological leaps beyond the London Underground (as my ex-Londoner friends here in Seoul don’t hesitate to remind me), but we can safely say that none will ever inspire quite so beloved a work of cartography.

An alternative version of the map can be viewed and downloaded at the David Rumsey Map Collection.

Related Content:

A Wonderful Archive of Historic Transit Maps: Expressive Art Meets Precise Graphic Design

London Mashed Up: Footage of the City from 1924 Layered Onto Footage from 2013

1927 London Shown in Moving Color

2,000 Years of London’s Historical Development, Animated in 7 Minutes

Prize-Winning Animation Lets You Fly Through 17th Century London

The Curious Story of London’s First Coffeehouses (1650–1675)

The Birth of London’s 1950s Bohemian Coffee Bars Documented in a Vintage 1959 Newsreel

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.