Mike Leigh works like few other directors. While most movies start with the script, Leigh develops a story and characters with his actors during long rehearsals. Leigh then assembles these exercises into a script. He will shoot some of that script and then rehearse some more. The result of this unusual style is that the actors know their characters down to the marrow. The film feels alive.

Back in 1975, just as Leigh was beginning to develop his famed method, the BBC commissioned him to make a series of five-minute movies. Leigh described the concept of the assignment to writer Sean O’Sullivan:

I thought it was a cracking idea, and I would have done forty of them or fifty – so you’d see them all the time, and sometimes you might see a character you never saw again, sometimes you might see somebody popping up for a moment and then be a main character in another one, or there’d be a couple of ones that would run on to a narrative. It would be a whole microcosm of the world. There was debate about whether they should be shown at the same time or they should be dotted around the channel, like currants in the pudding, as Tony Garnett, the producer, called it.

The project, sadly, was canceled before it even aired and only five movies were made. Those five were not broadcast until 1982 when Leigh had already become a big name in British television.

In some of his best works like Life is Sweet and Naked, Leigh focused on the small dramas of working class life, mining the unarticulated sadness and anger simmering just beneath the surface of modern Britain. His Five-Minute Films show early glimmers of his later greatness.

The plot of the first film, The Birth of the Goalie of the 2001 F.A. Cup Final, is simple to an extreme. The short, which consists of ten vignettes spanning a half-dozen years, is about a couple deciding whether or not to have a baby. The nameless bloke repeatedly asks his reluctant partner, “Wouldn’t it be great to have a kid?” At the end of the movie, he’s kicking the ball around with his young son. The end. It is almost as if Leigh wanted to see how little backstory and character psychology he could get away with.

The second film, Old Chums, is the diametrical opposite to the first – it’s all about character. The story, which unfolds in real-time, shows Brian, who is disabled and in crutches, walking to the car as he parries the conversational onslaught of a boorish ex-schoolmate, Terry. The movie buries you in names and long past events that have little bearing on the story, but leaves central questions like “what does Terry actually want?” tantalizingly vague.

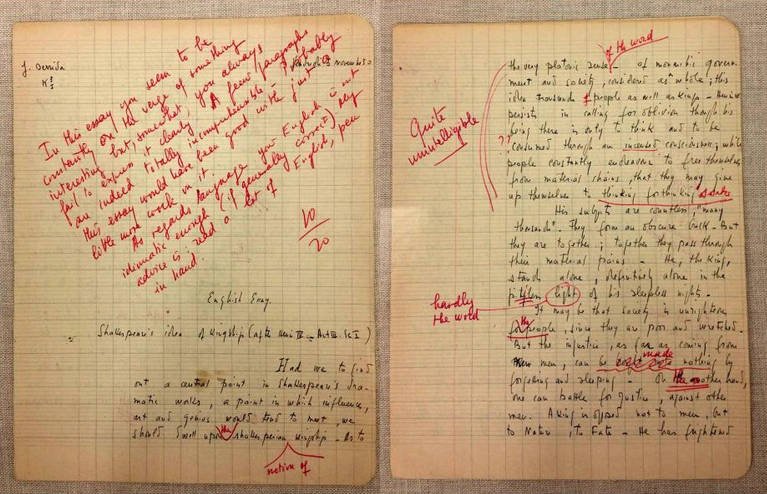

A third film, Probation, appears above. You can watch the remainder of Leigh’s Five-Minute Shorts here. We’ll also add them to our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

Tim Burton’s Early Student Films:King and Octopus & Stalk of the Celery Monster

Martin Scorsese’s Very First Films: Three Imaginative Short Works

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of badgers and even more pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.