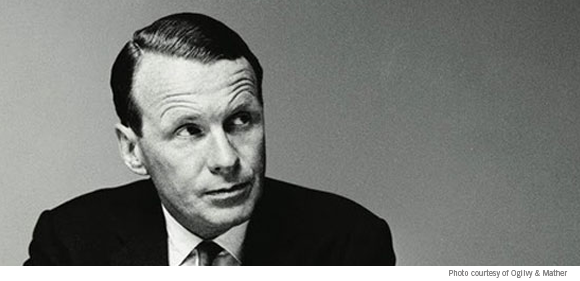

Hôtel de Lauzun, the meeting place of the Club des Hachichins

It may be cliché to say so, but there does seem to be a strong correlation between experiments with mind-altering chemicals and some of the most intriguing experiments in literary style. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Arthur Rimbaud, William S. Burroughs, Hunter S. Thompson…. Of course, it is necessary to point out that these talented writers were already that—talented writers—substances or no. As one of Rimbaud’s modern children, Patti Smith, declares, drugs are “not really how one accesses the imagination. It can be a tool, but when that tool starts to master you, you’ll lose touch with your craft.”

This seems to have happened to Smith’s literary idol. One of Rimbaud’s literary heroes, Charles Baudelaire, also eventually succumbed to his excessive use of laudanum, alcohol, and opium. But at one time, Baudelaire dabbled with a much less destructive drug, hashish, along with a coterie of other artists, including Alexandre Dumas, Gérard de Nerval, Victor Hugo, Honoré de Balzac, and painter Eugène Delacroix. The French greats gathered in a gothic house, from 1844–1849, under the moniker Club des Hachichins and partook of the drug, introduced to it by medical doctor Jacques-Joseph Moreau and writer and journalist Théophile Gautier. Writes The Guardian:

…ritualistically garbed in Arab clothing, they drank strong coffee, liberally laced with hashish, which Moreau called dawamesk, in the Arabic manner. It looked, reported the members, like a greenish preserve, its ingredients a mixture of hashish, cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, pistachio, sugar, orange juice, butter and cantharides. Some of them would write of their “stoned” experiences, although not all. Balzac attended the club but preferred not to indulge, though some time in 1845 the great man cracked and ate some. He told fellow members he had heard celestial voices and seen visions of divine paintings.

Baudelaire declared the hash admixture “the playground of the seraphim” and “a little green sweetmeat.” And yet, like Balzac, he “rarely, if indeed ever, indulged.” Gautier would write of the poet, “It is possible and even probable that Baudelaire did try hascheesh once or twice by way of physiological experiment, but he never made continuous use of it. Besides, he felt much repugnance for that sort of happiness, bought at the chemist’s and taken away in the vest-pocket.”

This “repugnance” did not keep Baudelaire from other drugs. And it did not keep him from writing a short book in 1860 on hash and opium, Artificial Paradises (Les Paradis Artificiels). The Paris Review reprints an excerpt of one section, “The Poem of Hashish”—not in fact a poem, but a descriptive essay. Translated by Aleister Crowley—another writer whose experiments with chemical excess contributed to some of the strangest books written in English—Baudelaire’s prose is almost medical in its precision. In part a response to Thomas de Quincy’s 1821 drug memoir Confession’s of an English Opium Eater, the symbolist poet’s treatise does not draw the conclusions one might expect.

Though he writes stunningly vivid, almost seductive, descriptions of hash intoxication, instead of praising the creative effects of drugs, Baudelaire disparages their use and warns of addiction, especially for the artist. At one point, he writes, “He who would resort to a poison in order to think would soon be incapable of thinking without the poison. Can you imagine this awful sort of man whose paralyzed imagination can no longer function without the benefit of hashish or opium?” Baudelaire recognized these stifling effects even as he lapsed into addiction himself, describing in withering terms the search “in pharmacy” for an escape from “his habitaculum of mire.”

You can read an excerpt of the Crowley-translated “The Poem of Hashish” at The Paris Review’s site and the full translation here. Those who have indulged in their own cannabis experiments—legally or otherwise—will surely recognize the poetic accuracy of his hash portrait, so perfect that it’s hard to believe he didn’t partake at least once or twice at the all-star Club des Hachichins:

Hashish often brings about a voracious hunger, nearly always an excessive thirst … Such a state would not be supportable if it lasted too long, and if it did not soon give place to another phase of intoxication, which in the case above cited interprets itself by splendid visions, tenderly terrifying, and at the same time full of consolations. This new state is what the Easterns call Kaif. It is no longer the whirlwind or the tempest; it is a calm and motionless bliss, a glorious resignèdness. Since long you have not been your own master; but you trouble yourself no longer about that. Pain, and the sense of time, have disappeared; or if sometimes they dare to show their heads, it is only as transfigured by the master feeling, and they are then, as compared with their ordinary form, what poetic melancholy is to prosaic grief.

via The Paris Review

Related Content:

Carl Sagan Extols the Virtues of Cannabis (1969)

The Coffee Pot That Fueled Honoré de Balzac’s Coffee Addiction

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness