Last year, after parting ways with a punishing, thankless corporate job but before my wife gave birth to my first child, my friend invited me to participate in the From Dusk til Drawn fundraiser at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Santa Barbara. Basically, it involved drawing for 24 straight hours. At that point in my life – i.e. before children – sleep deprivation was a novelty. It sounded insane. I was in.

I knew I needed a system. The last thing I wanted was to be struggling for ideas of something to draw at four in the morning. So after some debate, I decided to draw portraits of all 47 vice presidents of the United States. With octopuses on their heads. Why?

It probably started with Walter Mondale. I was on the couch with my mother watching the returns for the 1984 election. When it became clear that he was not going to become America’s next chief executive, my mother, who spent her formative years in Berkeley during the thick of the ‘60s, stood up, proclaimed “Well, shit!” and stormed upstairs. I was in seventh grade. This was the first election I cared about. Mondale had reached for glory and failed spectacularly. Starting that night, I became fascinated with those who aspired to history but ended up a footnote. So obviously, I became interested in vice presidents.

The Constitution is surprisingly vague on the veep. Vice President Charles Dawes — a man who won a Nobel Peace Prize and who wrote a tune that would later become a pop hit, all before becoming Calvin Coolidge’s number two guy — summed up the job while talking with senator and future VP Alben W. Barkley like this: “I can do only two things here. One of them is to sit up here on this rostrum [in the Senate] and listen to you birds talk without the ability to reply. The other is to look at the newspapers every morning to see how the President’s health is.”

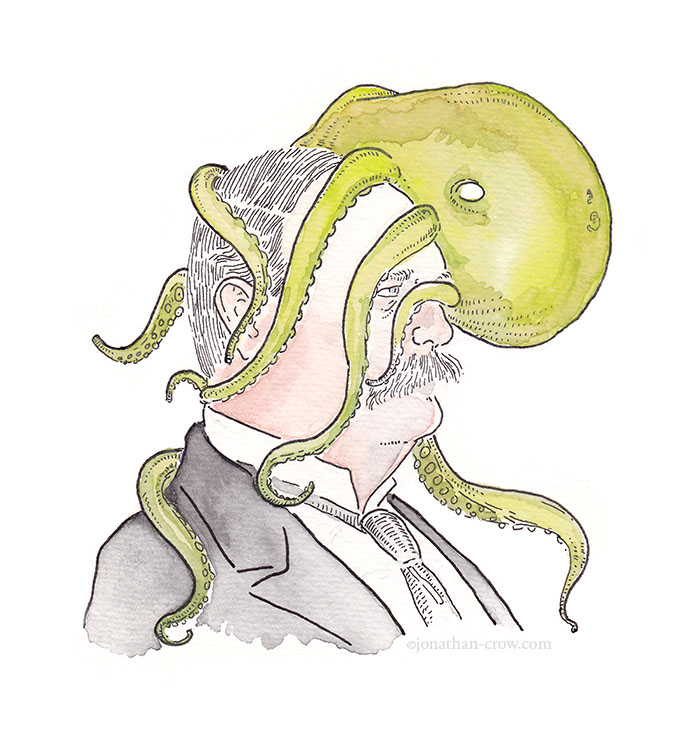

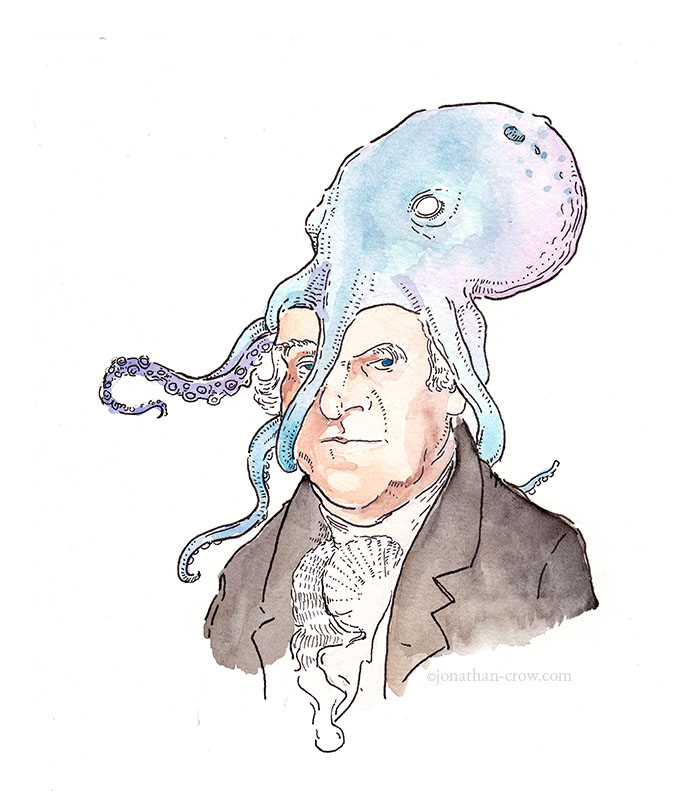

Though the position bestows on it all of the authority and pomp of the U.S. Government, vice presidents throughout history have struggled to find purpose in a poorly defined role, all the while waiting for death. It’s a bit like life itself. A few, through ambition, talent and a lot of luck, ascended to the top job. Most moldered in obscurity. No wonder then that John Nance Garner, one of FDR’s three VPs, called the job “not worth a bucket of warm piss.” I added the octopuses because I thought they were funny. It takes a rare person to pull off an air of dignity with a cephalopod on his head. It seems to fit with the absurdity of the job.

During From Dusk til Drawn, I was a machine. I cranked out 22 portraits of vice presidents in 24 hours. That’s one an hour, excluding a 2am jaunt to get a rice bowl and a handful of bathroom breaks. Over the next year, I drew and redrew them all from John Adams to Joe Biden and then, starting this past July, I began posting one picture a day on my site Veeptopus. I’m up to Hubert H. Humphrey now. During this time, I learned a lot about formerly important people who are now almost entirely unknown. People like William R. King, who died of tuberculosis three weeks after getting sworn in as VP, or John Breckinridge, who fled to Cuba to avoid getting arrested for treason. You can see the fruits of my crazy scheme here. I hope you enjoy.

Above, in descending order, you can find portraits of 1) Garret Hobart (1897–1899), the 24th Veep under William McKinley; 2) Thomas Jefferson, who bucked the VP trend and made something of himself; and 3) George Clinton who served under Jefferson and Madison. Don’t confuse him with the guy from Parliament Funkadelic.

Related Content:

Watch a Witty, Gritty, Hardboiled Retelling of the Famous Aaron Burr-Alexander Hamilton Duel

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And you can check out his online Veeptopus store here.