“I love the smell of napalm in the morning.” There we have undoubtedly the most famous quote of what must count as one of Robert Duvall’s finest performances, and surely his most surprising: that of Lieutenant Colonel Bill Kilgore in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. As you’ll no doubt recall — and if you don’t recall it, minimize your browser for a few hours and make your way to a screening, or at least watch it online — Captain Benjamin Willard’s Conradian boat journey into the Vietnam War’s dark heart hits a snag fairly early in the picture: they need to pass through a coastal area under tight Viet Cong control.

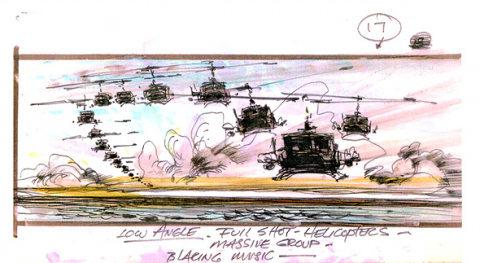

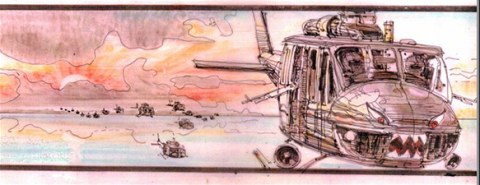

Kilgore, initially reluctant to call in his helicopters to back up Willard’s dubious mission, changes his mind when he realizes that Willard counts among his own small crew famed professional surfer Lance B. Johnson. The Lieutenant Colonel, it turns out, loves to surf. He also loves to blast Richard Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” from helicopter-mounted speakers. “It scares the hell out of the slopes,” he explains. “My boys love it.”

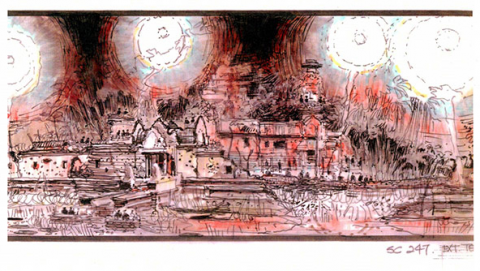

At the top, you can watch the fruits of Willard and Kilgore’s cooperation, an operatic napalm airstrike that takes the entire beach: not an easy thing to accomplish, and certainly not an easy thing to film. As anyone acquainted with the making of Apocalypse Now has heard, the production tended to turn as complicated, confusing, and perilous as the Vietnam War itself, but not necessarily for lack of planning.

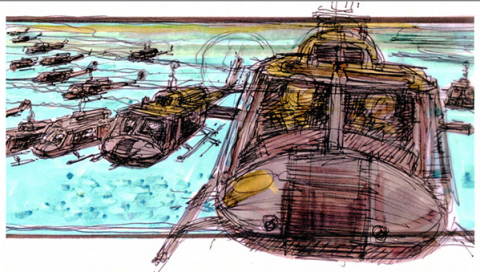

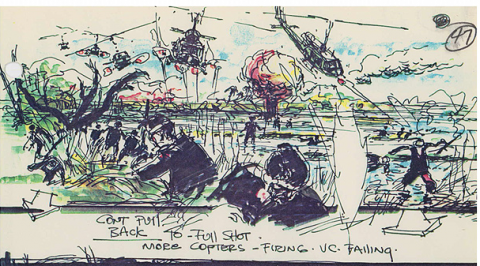

At Empire, you can view the scene’s original storyboards and read alongside them a brief interview with Doug Claybourne, who on the film had the enviable title of Helicopter Wrangler. Arriving to the Philippines-based shoot (in “the middle of nowhere”), Claybourne found Coppola on the beach with a bullhorn, Martin Sheen just replacing Harvey Keitel in the role of Willard, choppers borrowed from President Ferdinand Marcos (who periodically took them back to use against insurrections elsewhere), a coming typhoon, and “a lot of chaos.”

But Coppola, Claybourne, and the rest of the team saw it through, achieving results even more striking, in moments, than these storyboards suggest. As for the unflappable Kilgore, well, we all remember him rushing to catch a tantalizing wave even before the fighting subsides. After all, to quote his second-most famous line, “Charlie don’t surf!”

Related Content:

Akira Kurosawa & Francis Ford Coppola Star in Japanese Whisky Commercials (1980)

Dementia 13: The Film That Took Francis Ford Coppola From Schlockster to Auteur

Francis Ford Coppola’s Handwritten Casting Notes for The Godfather

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.