Given the way nineteenth-century literature is sometimes conceived—as the special province of a few great, hairy celebrity novelists—one might imagine that a meeting between Charles Dickens and Fyodor Dostoevsky would not be an unusual occurrence. Maybe it was even routine, like Jay Z and Kanye bumping elbows at a party! So when I read that the two had once met, in London in 1862, my first thought was, “well, sure. And then Herman Melville and Gustave Flaubert stopped by, and they got into a brawl over the check.” Alright, that’s ridiculous. Melville didn’t achieve any degree of fame until after his death, after all, and while the other three were respected, even wildly famous (in Dickens’ case), it is unlikely they read much of each other, much less traveled hundreds of miles for personal visits.

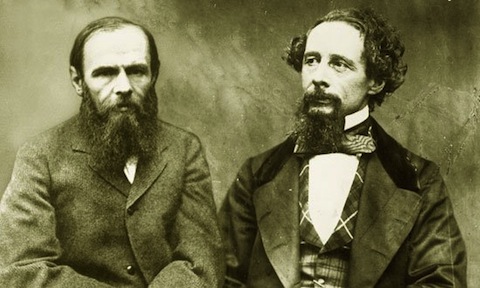

And yet, the story of Dickens and Dostoevsky—since revealed to be as much a fabrication as the image above—was plausible enough to find purchase in two recent Dickens biographies. Though the two men had vastly different sensibilities, their shared experiences of the seamier side of life, and their sprawling serialized novels cataloguing their time’s social ills in great detail, would seem likely to draw them together. New York Times literary critic Michiko Kakutani seemed to think so when she repeated the story as told in Claire Tomalin’s 2011 Charles Dickens, A Life. Tomalin—who found the story in the Dickensian, the journal of the Dickens Fellowship, and reported it in good faith—recounts how the Russian novelist intentionally sought out his English counterpart in London, and, upon finding him, heard Dickens bare his soul, confessing that he longed to be like his honest, simple characters, but used his own personal failings to construct his villains.

The story might still have currency had not several Russian literature scholars read Kakutani’s review and found it far too credulous: Why would Dostoevsky have only mentioned the encounter in a letter written sixteen years after the fact, a letter no scholar has seen? What language would the two men have in common—and if they had one, probably French, would they be fluent enough to have a heart to heart? And even if Dostoevsky visited London in 1862, as it seems, he did, would he have intentionally sought out Charles Dickens? Eric Naiman, professor of Slavic Language and Literatures at UC Berkeley, doubted all of this, and, in undertaking some research, found it to be the elaborate production of a man named A.D. Harvey, who has created for himself a coterie of fictional academic identities so thorough as to constitute what Naiman calls a “community of scholars who can analyse, supplement and occasionally even ruthlessly criticise each other’s work.”

As far as literary hoaxers go, Harvey is quite accomplished. You may find his story—driven, as such things often are, by wounded ego, misplaced talent, vanity, and frustrated ambition—much more interesting than any supposed tête-à-tête between the Russian and British novelists. A recent Guardian piece profiles the “man behind the great Dickens and Dostoevsky hoax,” and Eric Naiman’s exhaustive Times Literary Supplement expose of the hoax shows us just how deeply embedded such spurious lore can become in a literary community before it can be rooted out by skeptical scholars. The lesson here is trite, I guess. Don’t believe everything you read. But when we’re inclined—mostly for good reasons—to trust the word of those who pose as experts and authorities, this can be a hard lesson to heed.

Related Content:

Find works by Dostoevsky and Dickens in our collections of Free Audio Books and Free eBooks.

Albert Camus Talks About Adapting Dostoyevsky for the Theatre, 1959

Watch Piotr Dumala’s Wonderful Animations of Literary Works by Kafka and Dostoevsky

Celebrate the 200th Birthday of Charles Dickens with Free Movies, eBooks and Audio Books

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him at @jdmagness