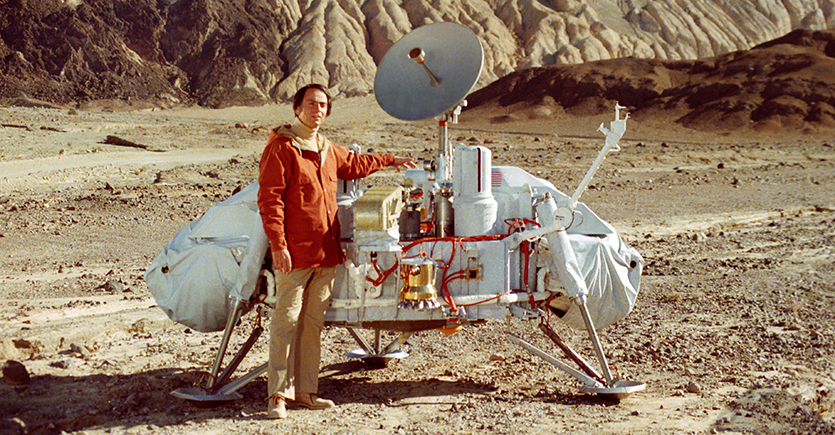

Photo by NASA via Wikimedia Commons

It is sometimes said that science and philosophy have grown so far apart that they no longer recognize each other. Perhaps they no longer need each other. And yet some of the most thoughtful scientists of modernity—those who most dedicated their lives not only to discovering nature’s mysteries, but to communicating those discoveries with the rest of us—have been fully steeped in a philosophical tradition. This especially goes for Carl Sagan, perhaps the greatest science communicator of the past century or so.

Sagan wrote a number of popular books for layfolk in which he indulged not only his tendencies as a “hopeless romantic,” writes Maria Popova, but also as a “brilliant philosopher.” He did not fear to venture into the realms of spiritual desire, and did not mock those who did likewise; and yet Sagan also did not hesitate to defend reason against “society’s most shameless untruths and outrageous propaganda.” These undertakings best come together in Sagan’s The Demon-Haunted World, a book in which he very patiently explains how and why to think scientifically, against the very human compulsion to do anything but.

In one chapter of his book, “The Fine Art of Baloney Detection,” Sagan laid out his method, proposing what he called “A Baloney Detection Kit,” a set of intellectual tools that scientists use to separate wishful thinking from genuine probability. Sagan presents the contents of his kit as “tools for skeptical thinking,” which he defines as “the means to construct, and to understand, a reasoned argument and—especially important—to recognize a fallacious or fraudulent argument.” You can see his list of all eight tools, slightly abridged, below. These are all in Sagan’s words:

- Wherever possible there must be independent confirmation of the “facts.”

- Encourage substantive debate on the evidence by knowledgeable proponents of all points of view.

- Arguments from authority carry little weight — “authorities” have made mistakes in the past. They will do so again in the future. Perhaps a better way to say it is that in science there are no authorities; at most, there are experts.

- Spin more than one hypothesis. If there’s something to be explained, think of all the different ways in which it could be explained. Then think of tests by which you might systematically disprove each of the alternatives.

- Try not to get overly attached to a hypothesis just because it’s yours. It’s only a way station in the pursuit of knowledge. Ask yourself why you like the idea. Compare it fairly with the alternatives. See if you can find reasons for rejecting it. If you don’t, others will.

- If whatever it is you’re explaining has some measure, some numerical quantity attached to it, you’ll be much better able to discriminate among competing hypotheses. What is vague and qualitative is open to many explanations.

- If there’s a chain of argument, every link in the chain must work (including the premise) — not just most of them.

- Occam’s Razor. This convenient rule-of-thumb urges us when faced with two hypotheses that explain the data equally well to choose the simpler. Always ask whether the hypothesis can be, at least in principle, falsified…. You must be able to check assertions out. Inveterate skeptics must be given the chance to follow your reasoning, to duplicate your experiments and see if they get the same result.

See the unabridged list at Brain Pickings, or read Sagan’s full chapter, ideally by getting a copy of The Demon-Haunted World. As Popova notes, Sagan not only gives us succinct instructions for critical thinking, but he also makes a thorough list, with definitions, of the ways reason fails us through “the most common and perilous fallacies of logic and rhetoric.” Sagan’s chapter on “Baloney Detection” is, like the rest of the book, a highly literary, personal, engagement with the most pressing scientific considerations in our everyday life. And it is also an informal yet rigorous restatement of Aristotle’s classical logic and rhetoric and Francis Bacon’s natural philosophy.

Related Content:

The Wisdom of Carl Sagan Animated

Richard Feynman Creates a Simple Method for Telling Science From Pseudoscience (1966)

Noam Chomsky Calls Postmodern Critiques of Science Over-Inflated “Polysyllabic Truisms”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness