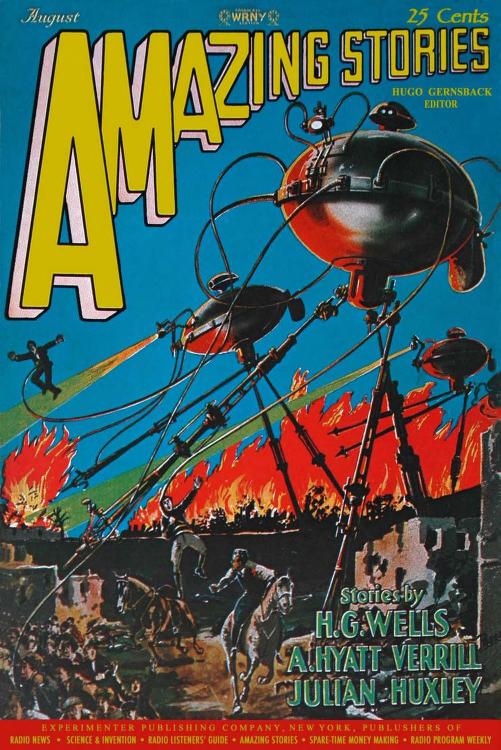

If you haven’t heard of Hugo Gernsback, you’ve surely heard of the Hugo Award. Next to the Nebula, it’s the most prestigious of science fiction prizes, bringing together in its ranks of winners such venerable authors as Ursula K. Le Guin, Arthur C. Clarke, Robert Heinlein, Neil Gaiman, Isaac Asimov, and just about every other sci-fi and fantasy luminary you could think of. It is indeed fitting that such an honor should be named for Gernsback, the Luxembourgian-American inventor who, in April of 1926, began publishing “the first and longest-running English-language magazine dedicated to what was then not quite yet called ‘science fiction,’” notes University of Virginia’s Andrew Ferguson at The Pulp Magazines Project. Amazing Stories provided an “exclusive outlet” for what Gernsback first called “scientifiction,” a genre he would “for better and for worse, define for the modern era.” You can read and download hundreds of Amazing Stories issues, from the first year of its publication to the last, at the Internet Archive.

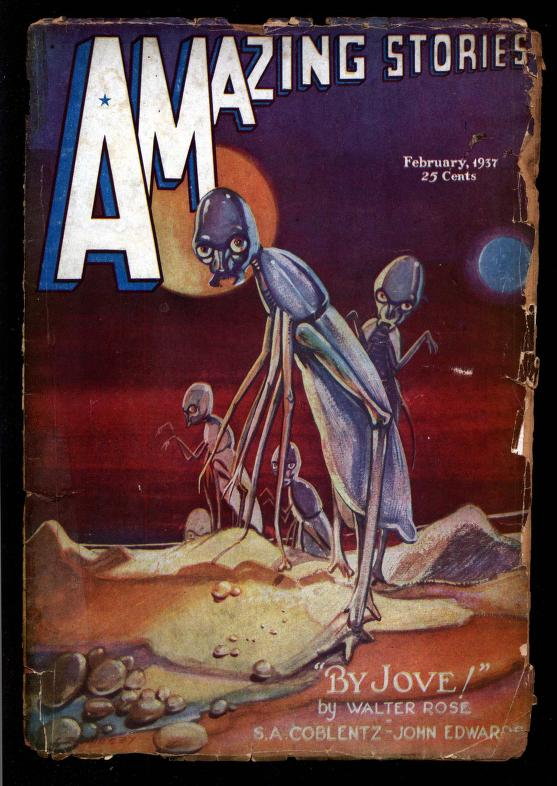

Like the extensive list of Hugo Award winners, the back catalog of Amazing Stories encompasses a host of geniuses: Le Guin, Asimov, H.G. Wells, Philip K. Dick, J.G. Ballard, and many hundreds of lesser-known writers. But the magazine “was slow to develop,” writes Scott Van Wynsberghe. Its lurid covers lured some readers in, but its “first two years were dominated by preprinted material,” and Gernsback developed a reputation for financial dodginess and for not paying his writers well or at all.

By 1929, he sold the magazine and moved on to other ventures, none of them particularly successful. Amazing Stories soldiered on, under a series of editors and with widely varying readerships until it finally succumbed in 2005, after almost eighty years of publication. But that is no small feat in such an often unpopular field, with a publication, writes Ferguson, that was very often perceived as “garish and nonliterary.”

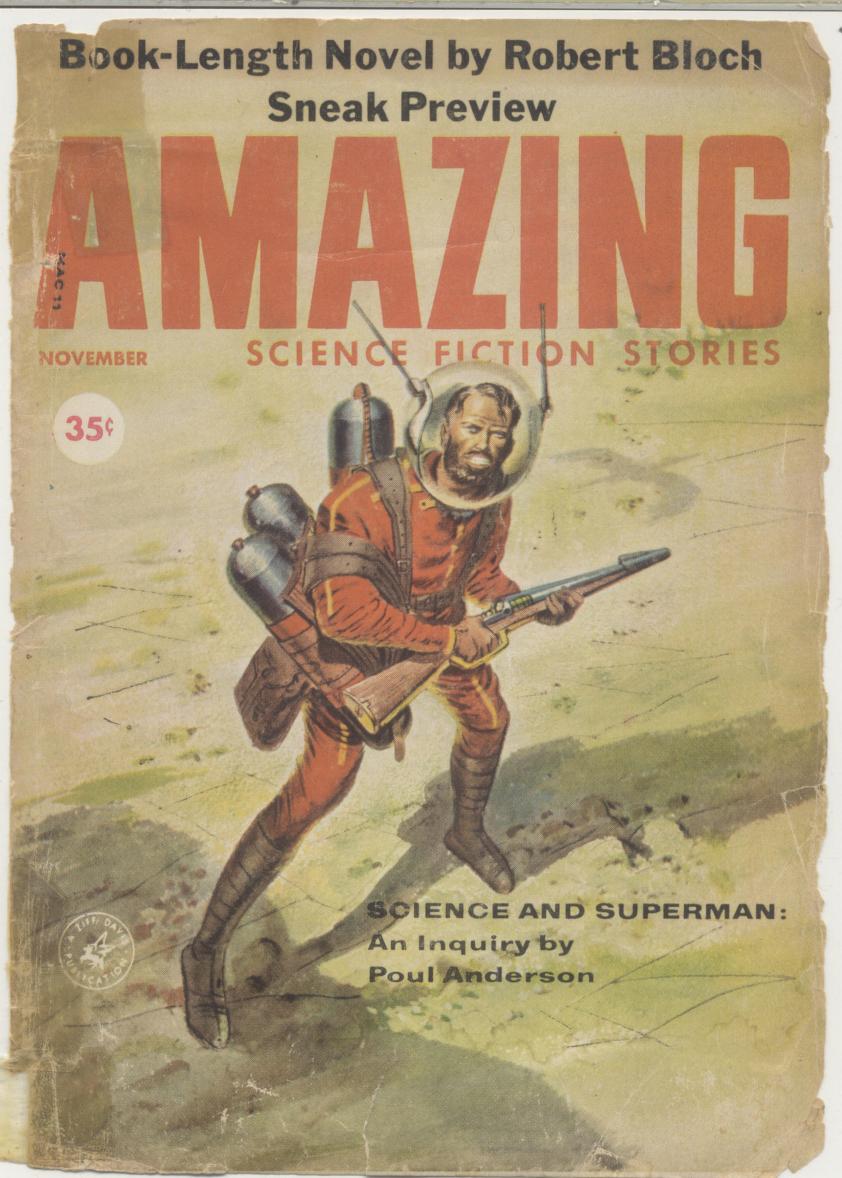

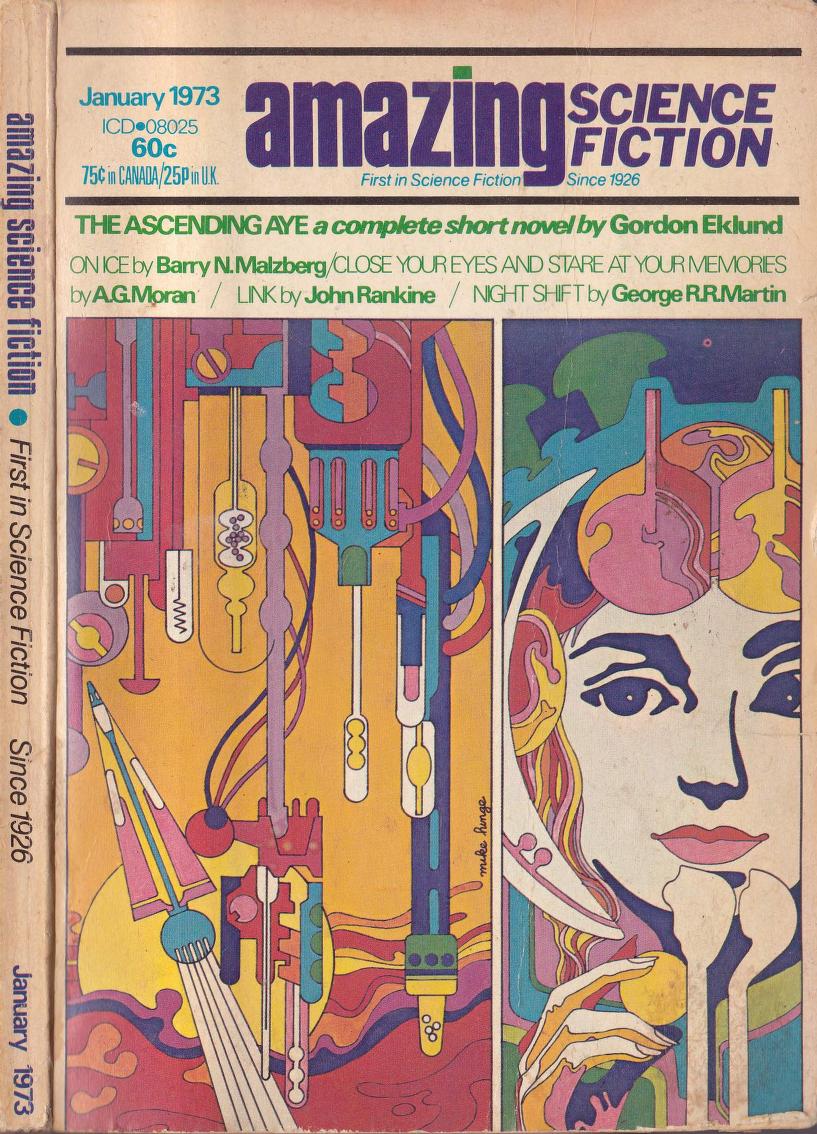

In hindsight, however, we can see Amazing Stories as a sci-fi time capsule and almost essential feature of the genre’s history, even if some of its content tended more toward the young adult adventure story than serious adult fiction. Its flashy covers set the bar for pulp magazines and comic books, especially in its run up to the fifties. After 1955, the year of the first Hugo Award, the magazine reached its peak under the editorship of Cele Goldsmith, who took over in 1959. Gone was much of the eyepopping B‑movie imagery of the earlier covers. Amazing Stories acquired a new level of relative polish and sophistication, and published many more “literary” writers, as in the 1959 issue above, which featured a “Book-Length Novel by Robert Bloch.”

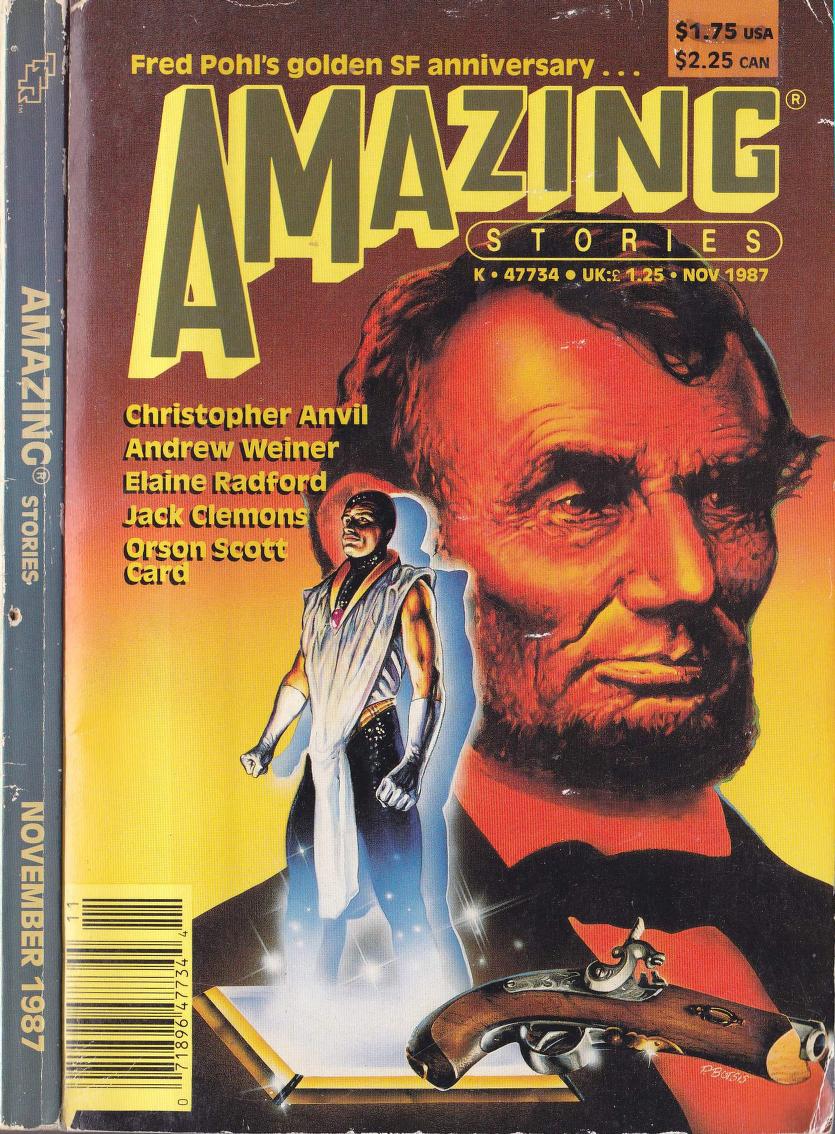

This trend continued into the seventies, as you can see in the issue above, with a “complete short novel by Gordon Eklund” (and early fiction by George R.R. Martin). In 1982, Ferguson writes, Amazing Stories was sold “to Gary Gygax of D&D fame, and would never again regain the prominence it had before.” The magazine largely returned to its pulp roots, with covers that resembled those of supermarket paperbacks. Great writers continued to appear, however. And the magazine remained an important source for new science fiction—though much of it only in hindsight. As for Gernsback, his reputation waned considerably after his death in 1967.

“Within a decade,” writes Van Wynsberghe, “science fiction pundits were debating whether or not he had created a ‘ghetto’ for hack writers.” In 1986, novelist Brian Aldiss called Gernsback “one of the worst disasters ever to hit the science fiction field.” His 1911 novel, the ludicrously named Ralph 124C 41+: A Romance of the Year 2660 is considered “one of the worst science fiction novels in history,” writes Matthew Lasar. It may seem odd that the Oscar of the sci-fi world should be named for such a reviled figure. And yet, despite his pronounced lack of literary ability, Gernsback was a visionary. As a futurist, he made some startlingly accurate predictions, along with some not-so-accurate ones. As for his significant contribution to a new form of writing, writes Lasar, “It was in Amazing Stories that Gernsback first tried to nail down the science fiction idea.” As Ray Bradbury supposedly said, “Gernsback made us fall in love with the future.” Enter the Amazing Stories Internet Archive here.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2017.

Related Content:

The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction: 17,500 Entries on All Things Sci-Fi Are Now Free Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness