Despite its status as one of the most widely known and studied epic poems of all time, Homer’s Iliad has proven surprisingly resistant to adaptation. However much inspiration it has provided to modern-day novelists working in a variety of different traditions, it’s translated somewhat less powerfully to visual media. Perhaps people still watch Wolfgang Petersen’s Troy, the very loose, Brad Pitt-starring cinematic Iliad adaptation from 2004. But chances are, a century or two from now, humanity on the whole will still be more impressed by the 52 illustrations of the Ambrosian Iliad, which was made in Constantinople or Alexandria around the turn of the sixth century.

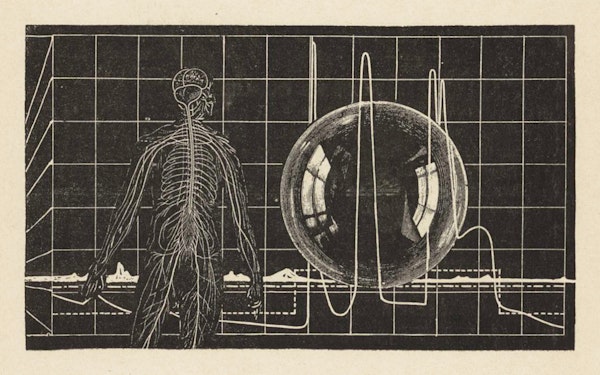

As noted at HistoryofInformation.com, “along with the Vergilius Vaticanus [previously featured on Open Culture] and the Vergilius Romanus, [the Ambrosian Iliad] is one of only three illustrated manuscripts of classical literature that survived from antiquity.” It’s also the only ancient manuscript that depicts scenes from the Iliad. Its illustrations, which “show the names of places and characters,” offer “an insight into early manuscript illumination.” They “show a considerable diversity of compositional schemes, from single combat to complex battle scenes,” as Kurt Weitzmann writes in Late Antique and Early Christian Book Illumination. “This indicates that, by that time, Iliad illustration had passed through various stages of development and thus had a long history behind it.”

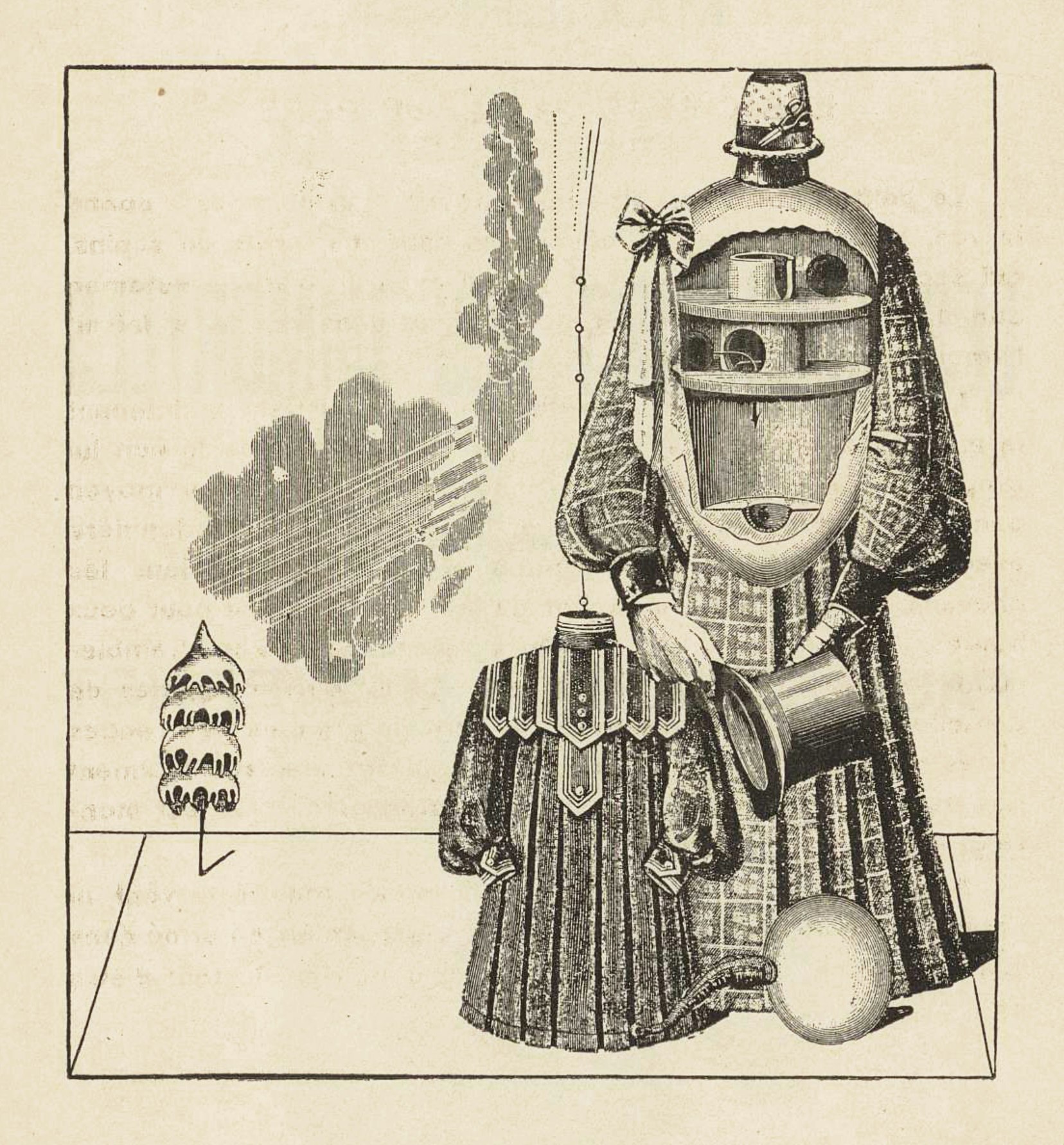

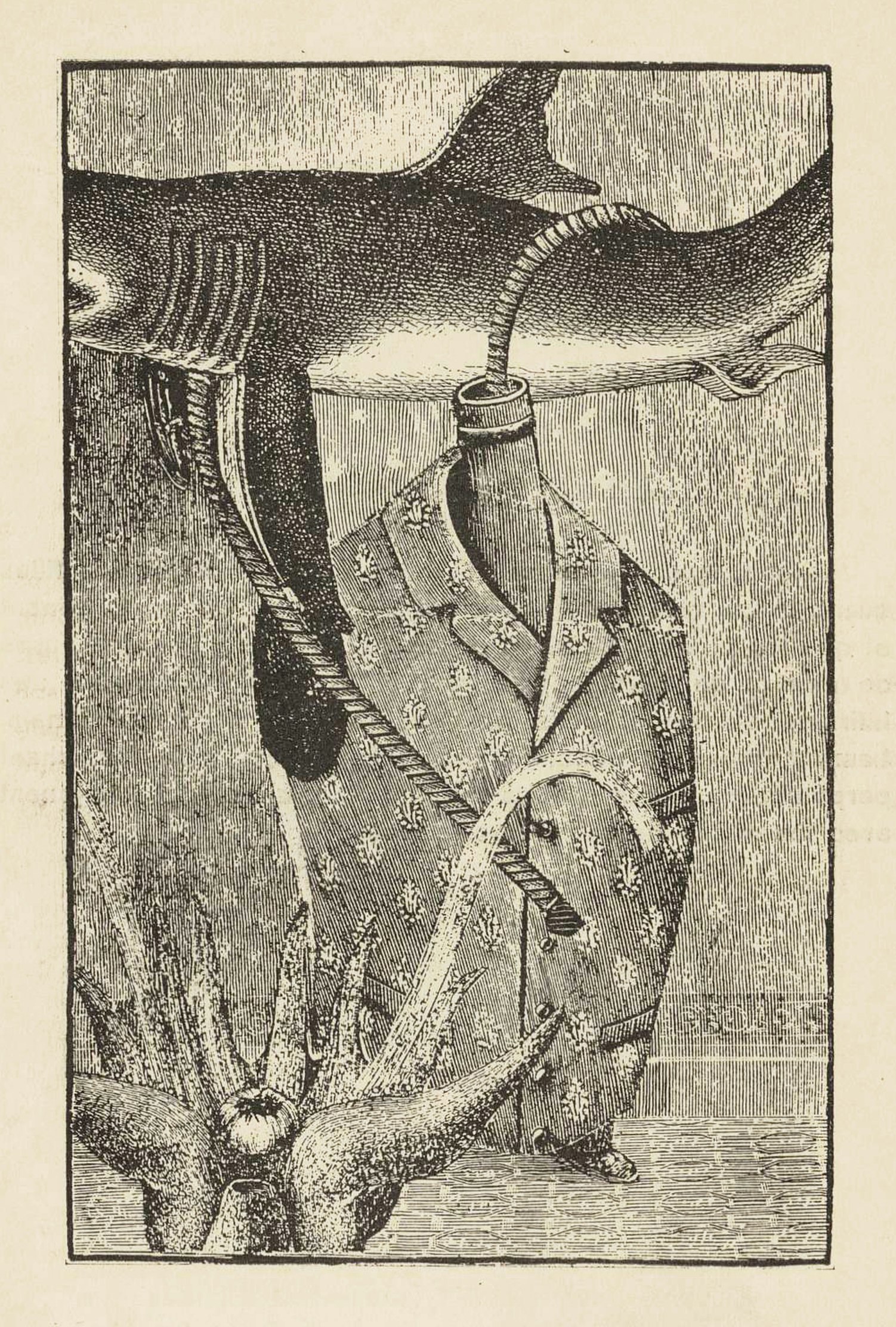

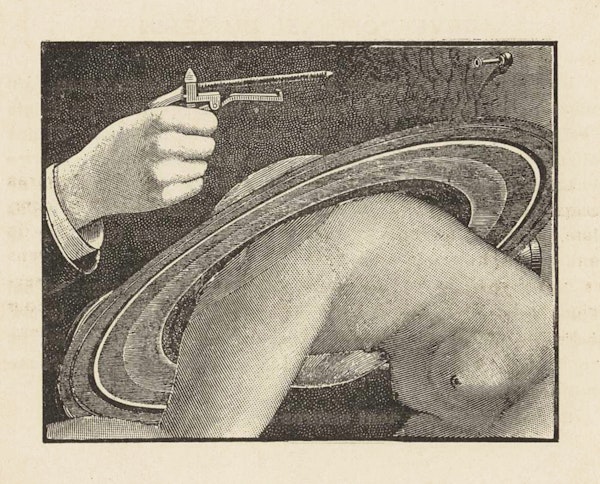

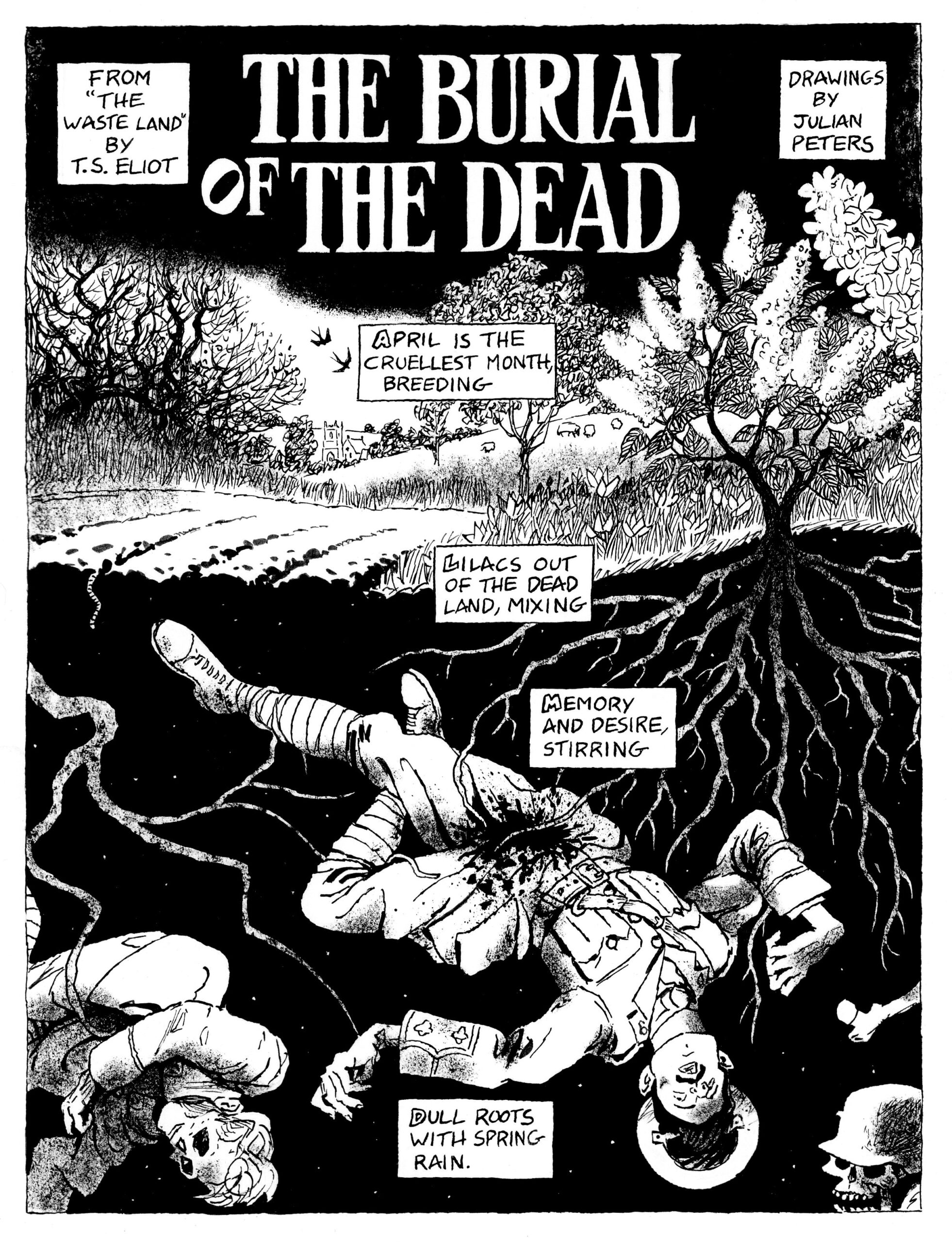

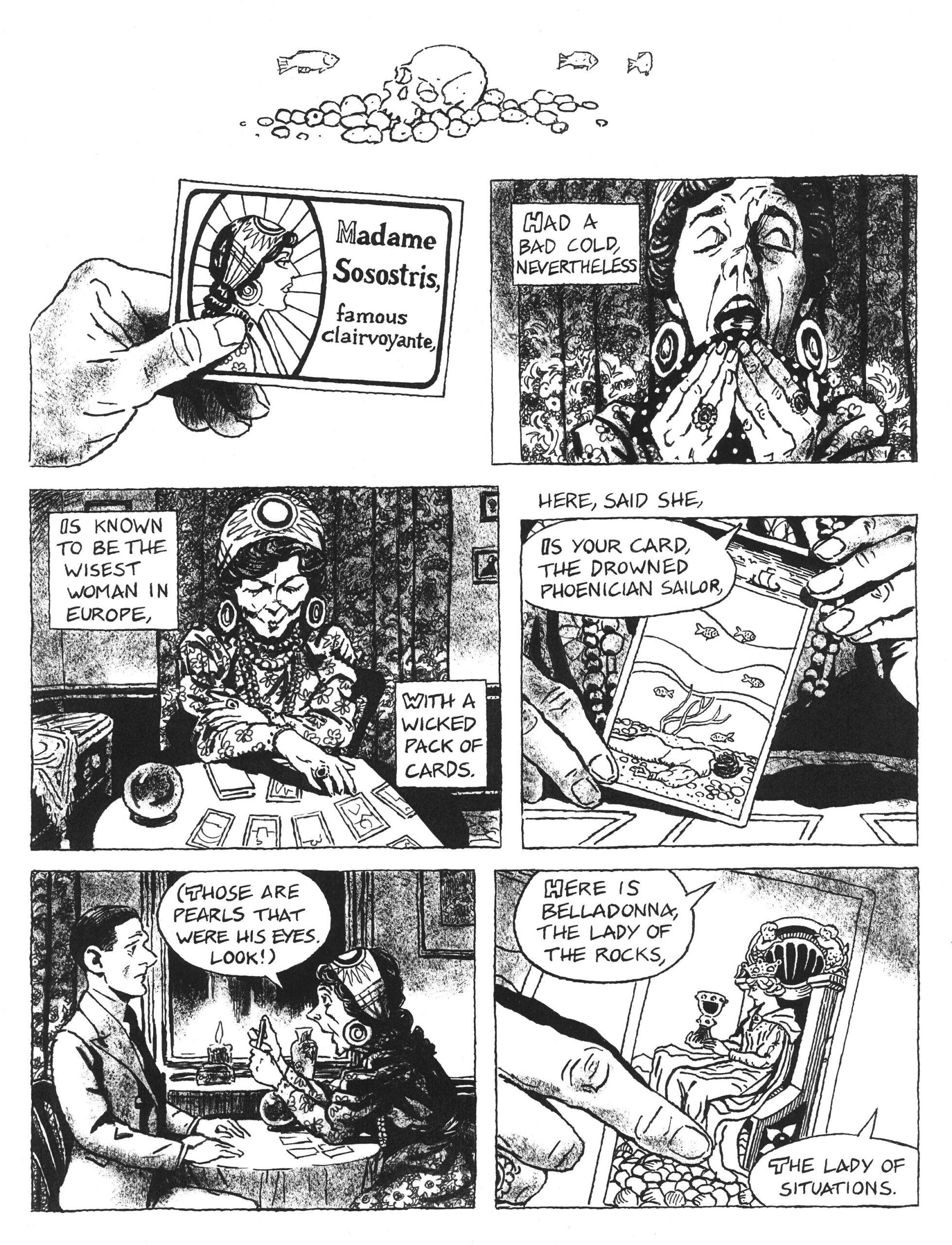

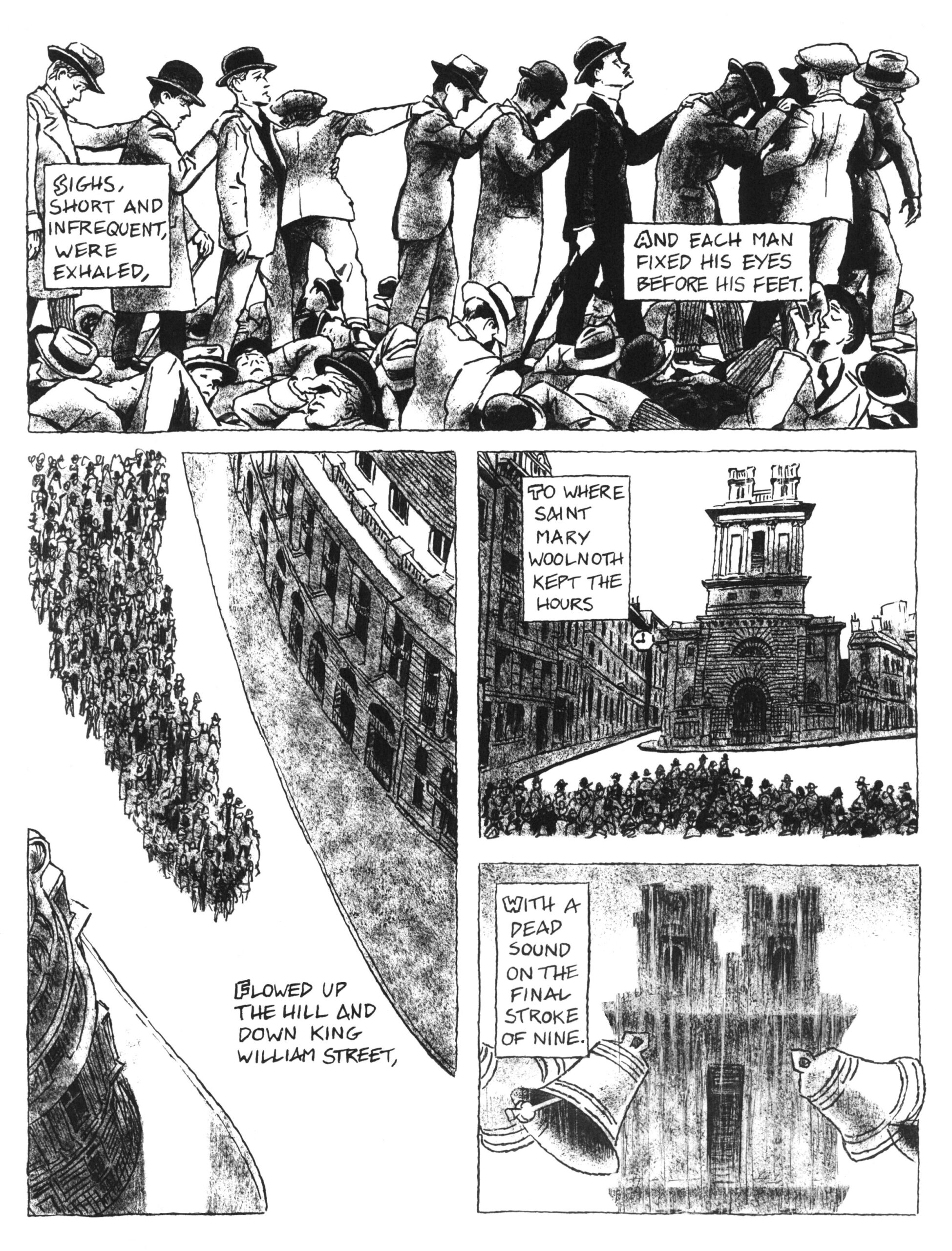

Above, you can see the Ambrosian Iliad’s illustrations of the capture of Dolon (top), Achilles sacrificing to Zeus for Patroclus’ safe return (middle), and Hector killing Patroclus as Automedon escapes (bottom). You can find more scans at the Warburg Institute Iconographic Database, along with other Iliad-related artifacts. Some of the later artistic renditions of Homer in that collection date from the fifteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, and even the nineteenth centuries, each interpreting these age-old poems for their own time. Indeed, the Iliad and Odyssey have proven enduringly resonant for the better part of three millennia, and there’s no reason to believe that they won’t continue to find new artistic forms for just as long to come. But there’s something especially powerful about seeing Homer rendered by artists who, though they may have come centuries and centuries after the blind poet himself, knew full well what it was to live in antiquity.

Related Content:

The Vatican Digitizes a 1,600-Year-Old Illuminated Manuscript of the Aeneid

A Handy, Detailed Map Shows the Hometowns of Characters in the Iliad

Hear Homer’s Iliad Read in the Original Ancient Greek

Hear Homer’s Iliad Read in the Original Ancient Greek

Greek Myth Comix Presents Homer’s Iliad & Odyssey Using Stick-Man Drawings

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.