Not many readers of the 21st century seek out the work of popular writers of the 19th century, but when they do, they often seek out the work of Jules Verne. Journey to the Center of the Earth, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Around the World in Eighty Days: fair to say that we all know the titles of these fantastical French tales from the 1860s and 70s, and more than a few of us have actually read them. But how many of us know that they all belong to a single series, the 54-volume Voyages Extraordinaires, that Verne published from 1863 until the end of his life? Verne described the project’s goal to an interviewer thus: “to conclude in story form my whole survey of the world’s surface and the heavens.”

Verne intended to educate, but at the same time to entertain and even artistically impress: “My object has been to depict the earth, and not the earth alone, but the universe,” he said. “And I have tried at the same time to realize a very high ideal of beauty of style.” This he accomplished with great success in a time and place without even what we would now consider a fully literate public.

As philosopher Marc Soriano writes of the 1860s when Verne began publishing, “The drive for literacy in France has been underway since the Guizot Law of 1833, but there is still much to do. Any well-advised editor must aid his readers who have not yet achieved a good reading proficiency.”

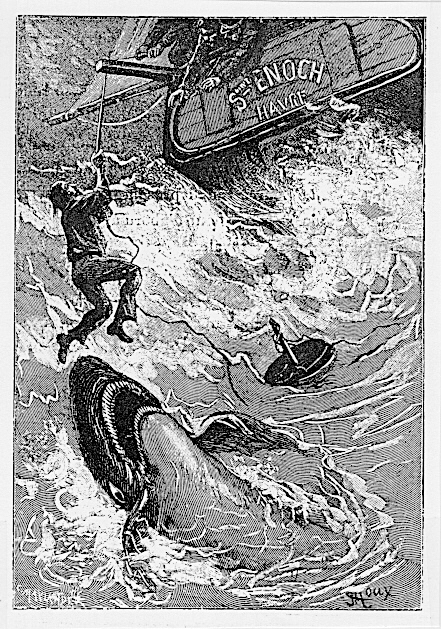

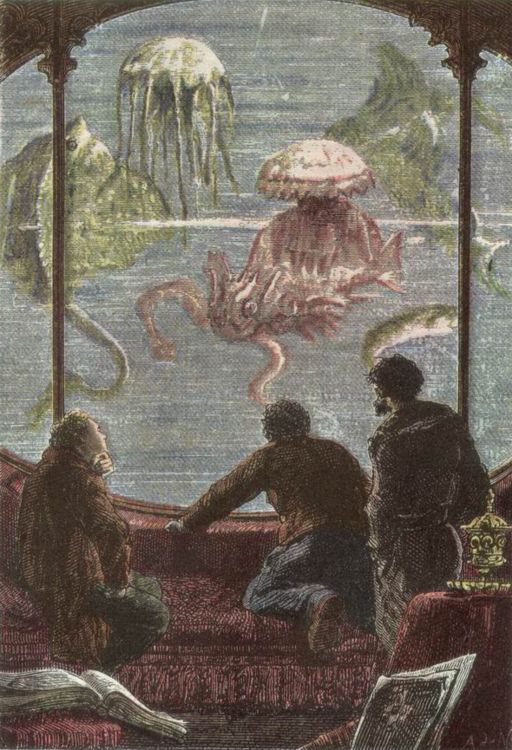

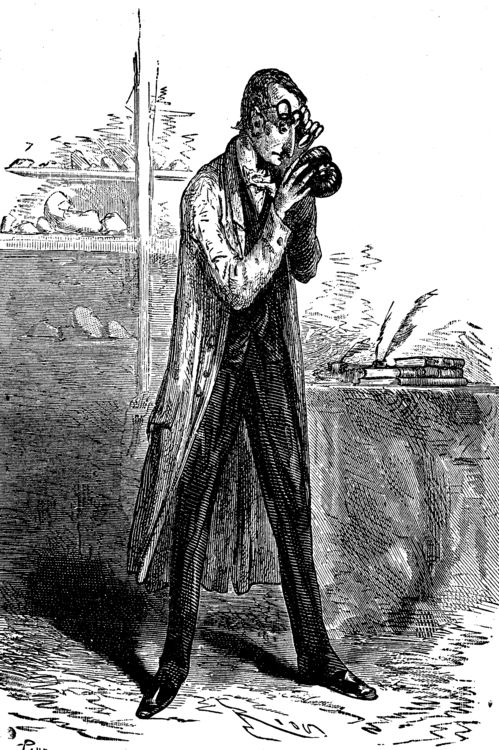

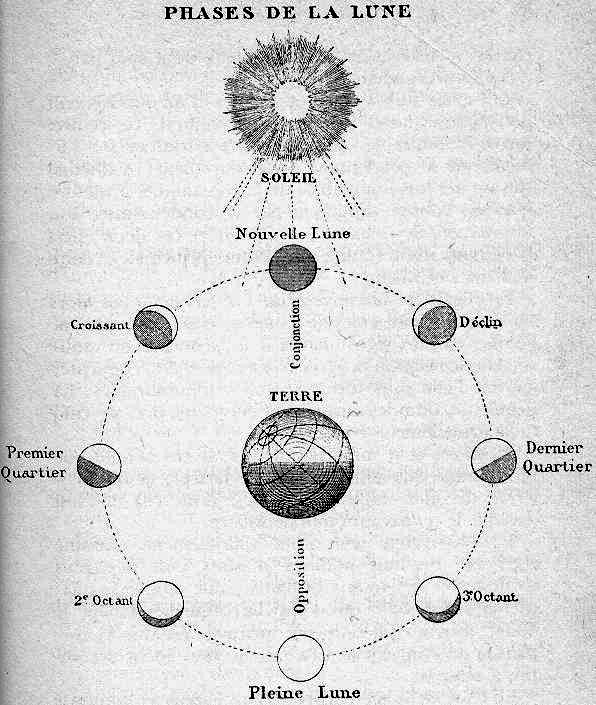

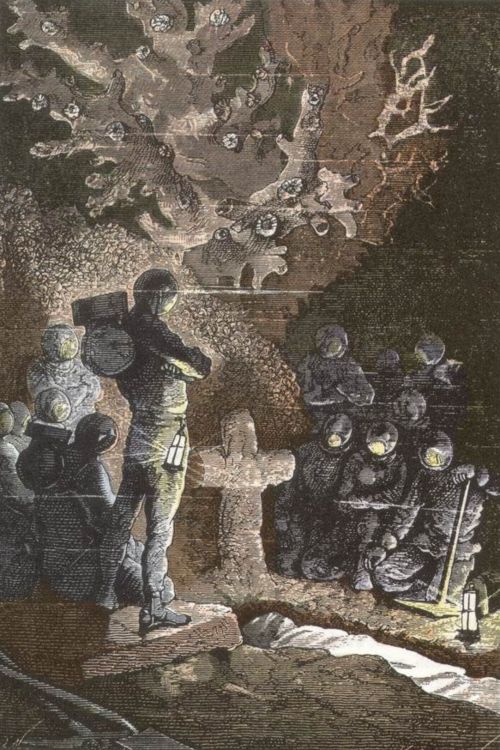

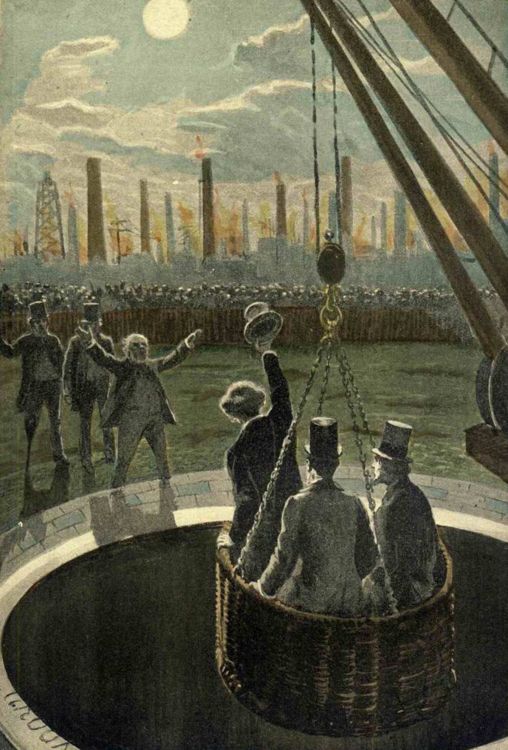

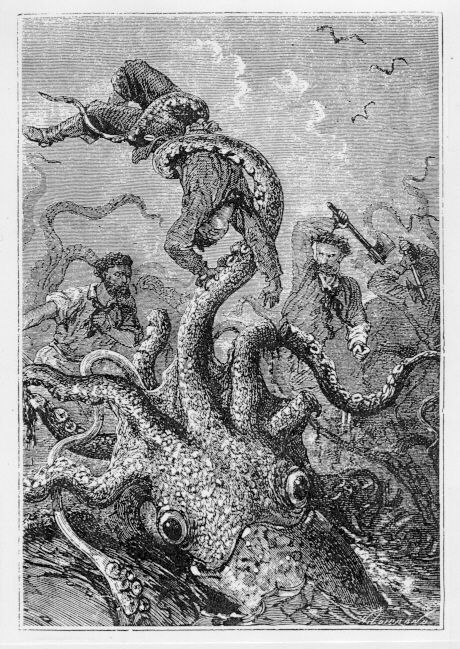

Hence the need for illustrations: beautiful illustrations, scientifically and narratively faithful illustrations, and above all a great many illustrations: over 4,000 of them, by the count of Arthur B. Evans in his essay on the series’ artists, “an average of 60+ illustrations per novel, one for every 6–8 pages of text.” Still today, “most modern French reprints of the Voyages Extraordinaires continue to feature their original illustrations — recapturing the ‘feel’ of Verne’s socio-historical milieu and evoking that sense of faraway exoticism and futuristic awe which the original readers once experienced from these texts. And yet, to date, the bulk of Vernian criticism has virtually ignored the crucial role played by these illustrations in Verne’s oeuvre.”

Evans identifies four different types of illustrations in the series: “renderings of the protagonists of the story — e.g., portraits like the one of Impey Barbicane in De la terre à la lune”; “panoramic and postcard-like” views of the “exotic locales, unusual sights, and flora and fauna which the heroes encounter during their journey, like the one from Vingt mille lieues sous les mers depicting divers walking on the ocean floor”; “documentational” illustrations like “the map of the Polar regions (hand-drawn by Verne himself) for his 1864 novel Les Voyages et aventures du capitaine Hatteras”; and portayals of “a specific moment of action in the narrative—e.g., the one from Voyage au centre de la terre where Prof. Lidenbrock, Axel, and Hans are suddenly caught in a lightning storm on a subterranean ocean.”

Verne and his editor Pierre-Jules Hetzel commissioned these illustrations from no fewer than eight artists, a group including Edouard Riou, Alphonse de Neuville, Emile-Antoine Bayard (previously featured here on Open Culture), and Léon Benett — all well-known artists in late 19th-century France, and made even more so by their work in the Voyages Extraordinaires. You can browse a complete gallery of the series’ original illustrations here, and if you like, enrich the experience with this extensive essay by Terry Harpold on “reading” these images in context.

Together with the stories themselves, on the back of which Verne remains the most translated science-fiction author of all time, they allow Harpold to make the credible claim that “the textual-graphic domain constituted by these objects is unmatched in its breadth and variety; no other corpus associated with a single author is comparable.” Human knowledge of the universe has widened and deepened since Verne’s day, but for sheer intellectual and adventurous wonder about what that universe might contain, has any writer, from any era or land, outdone him since?

Related Content:

How French Artists in 1899 Envisioned Life in the Year 2000: Drawing the Future

Petite Planète: Discover Chris Marker’s Influential 1950s Travel Photobook Series

The Art of Sci-Fi Book Covers: From the Fantastical 1920s to the Psychedelic 1960s & Beyond

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Thank you so much for this piece; I have read most of Verne’s Extraordinary Voyages, and yet, I did not know until now that they were formally part of one series.

>Human knowledge of the universe has widened and deepened since Verne’s day, but for sheer intellectual and adventurous wonder about what that universe might contain, has any writer, from any era or land, outdone him since?

Yes, we can safely say science fiction writers after Jules Verne has outdone him. Safely. I believe Jules Verne himself reading science fiction that came after himself would say so himself.

Believing that one moment in the past was better than all the future moments is a classic form of romantic nostalgia in the style of Midnight in Paris of Woody Allen.

I believe Jules Verne books were incredibile for the time and inspired millions of readers.

Believing that Jules Verne was the apex though is very sad. It’s absolutely the opposite of what Jules Verne was. Jules Verne was a dreamer believing in progress. When you believe that the Jules Verne was the apex of science fiction progress you are spitting in the face of his optimism.

I just concludud reading 20000 leagues under the Sea and was left astounded by the sheer futuristic descriptions of the submarine and technology used. I wish I had read this book half a century ago. Im 64 now and thoroughly enjoyed it. A true classic. Wish children today read it but sadly dont see that happening.

Jules Verne truly amazing, he is by far my favourite science fiction writer with william gibson, and i do read a lot of science fiction.

Fantastic article, thank you.

To anyone reading this, stay well and safe my friend.

Very informative and interesting post. I knew about Voyages Extraordinaires, but not the reason for all the wonderful illustrations. It would seem many of Verne’s contemporary readers may have struggled with his prose, but followed the stories better with the pictures.

What publishers call a “series” is more often considered a “publisher’s library.” Often a publisher would issue books under a heading like “𝑉𝑜𝑦𝑎𝑔𝑒𝑠 𝐸𝑥𝑡𝑟𝑎𝑜𝑟𝑑𝑖𝑛𝑎𝑟𝑒” for the convenience of advertising.

Most would imagine a “series” would have some continuity of plot or characters who are found in multiple stories. There is a little of this for Verne.

The obvious example are the three Moon stories — From the Earth to the Moon, Around the Moon, and the book variously published as Topsy Turvy or The Purchase of the North Pole. All feature characters from the Baltimore Gun Club. The last one is little known other than the Fitzroy edition in paperback from Ace.

Three of Verne’s longest stories, each comprising 18 months in Hetzel’s 𝑀𝑎𝑔𝑎𝑠𝑖𝑛 𝑑’𝑒́𝑑𝑢𝑐𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑒𝑡 𝑑𝑒 𝑟𝑒́𝑐𝑟𝑒́𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 or three volumes from his contractual commitment with the publisher, have characters which appear. However, contradictions in the stories make it impossible to create a cohesive narrative or timeline from them. The stories are Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas; Captain Grant’s Children / In Search of the Castaways / Voyage Round the World; and The Mysterious Island (originally published in three volumes). Some of the connections are slight such as a character or two from Castaways landing on the Mysterious Island.

There are several duologies among Verne’s stories such as Captain Hatteras; La Jangada (800 Leagues on the Amazon and The Cryptogram); The Steam House; the two stories about Robur (Robur the Conqueror / Clipper of the Clouds and Master of the World); Keraban the Inflexible; The Barsac Mission, and a couple others.

The Scribner Illustrated Classics or the Windermere series are called “series” by publishers but they are really publisher libraries reprinting classics with color plate illustrations. Hetzel was the first publisher (in France) of the Verne stories but calling them a “series” can lead to misinterpretations.

If you are going to read Verne in English, get good modern translations. The old ones are usually very bad and omit large portions of the stories such as an entire chapter that describes the interior of the Nautilus. You wouldn’t want to miss that.

Very few people even knew the Verne wrote anything besides 20000 leagues (sp) Under the Sea. I remember a few other titles like “The Demon of Cowper (sp) sorry. The Village in the Treetops and others.Being born with Dyslexia I did not learn to read until I was 14. The first book I chose to read? 20000 leagues under the sea. My spelling is still rusty but my lust for science fiction was kindled as was my love of pipe organ and Bach. Bon Chance Friends.