Children’s books are big business. And the market has never been more competitive. Bestselling, character-driven series spawn their own TV shows. Candy-colored readers feature kids’ favorite comic and cartoon characters. But kids’ books can also be fine art—a venue for well-written, finely-illustrated literature. And they are a serious subject of scholarship, offering insights into the histories of book publishing, education, and the social roles children were taught to play throughout modern history.

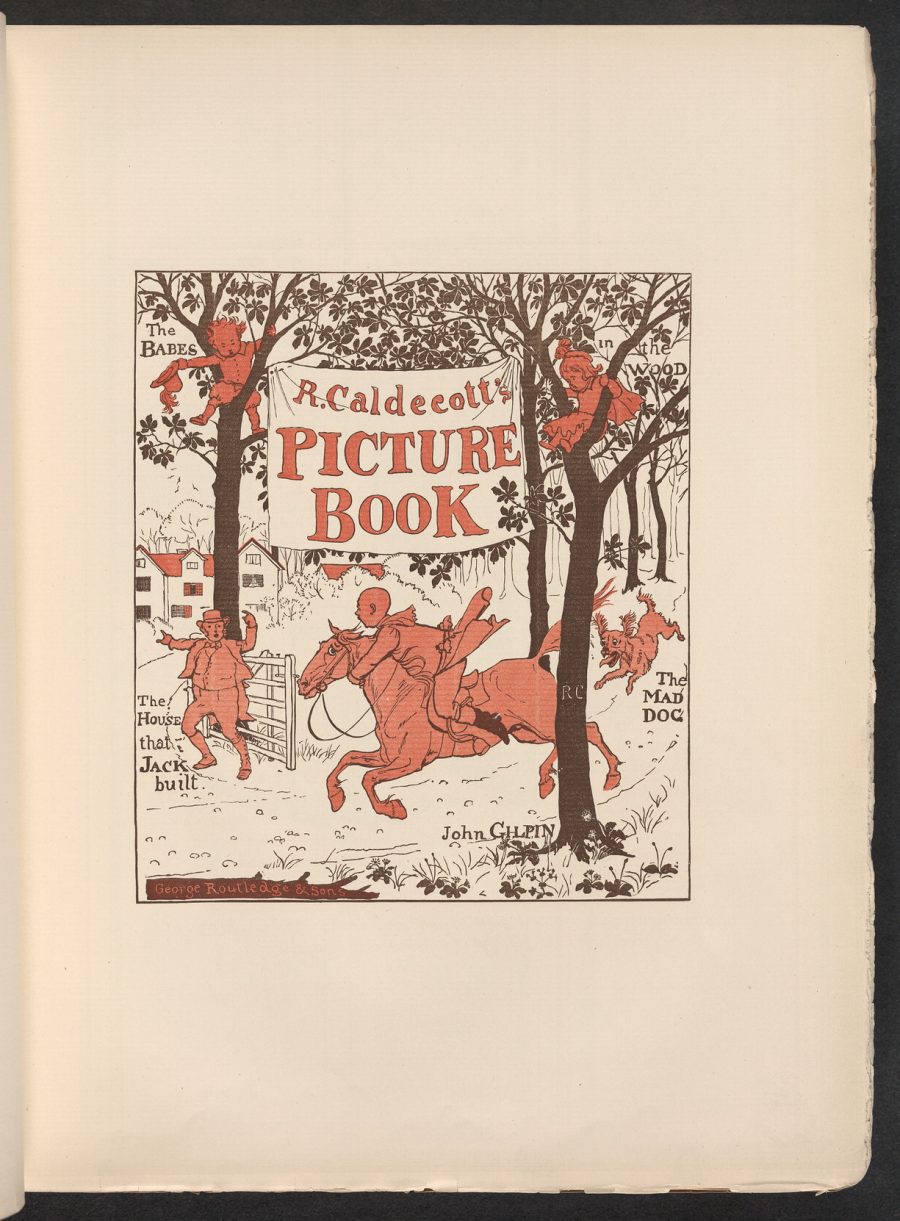

Digital archives of children’s books now make these histories widely accessible and preserve some of the finest examples of illustrated children’s literature. The Library of Congress’ new digital collection, for example, includes the 1887 Complete Collection of Pictures & Songs, illustrated by English artist Randolph Caldecott, who would lend his name fifty years later to the medal distinguishing the highest quality American picture books.

The LoC’s collection of 67 digitized kids’ books from the 19th and 20th centuries includes biographies, nonfiction, quaint nursery rhymes, the Gustave Doré-illustrated edition of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven, and a number of other titles sure to charm grown-ups, if not, perhaps, many of today’s young readers.

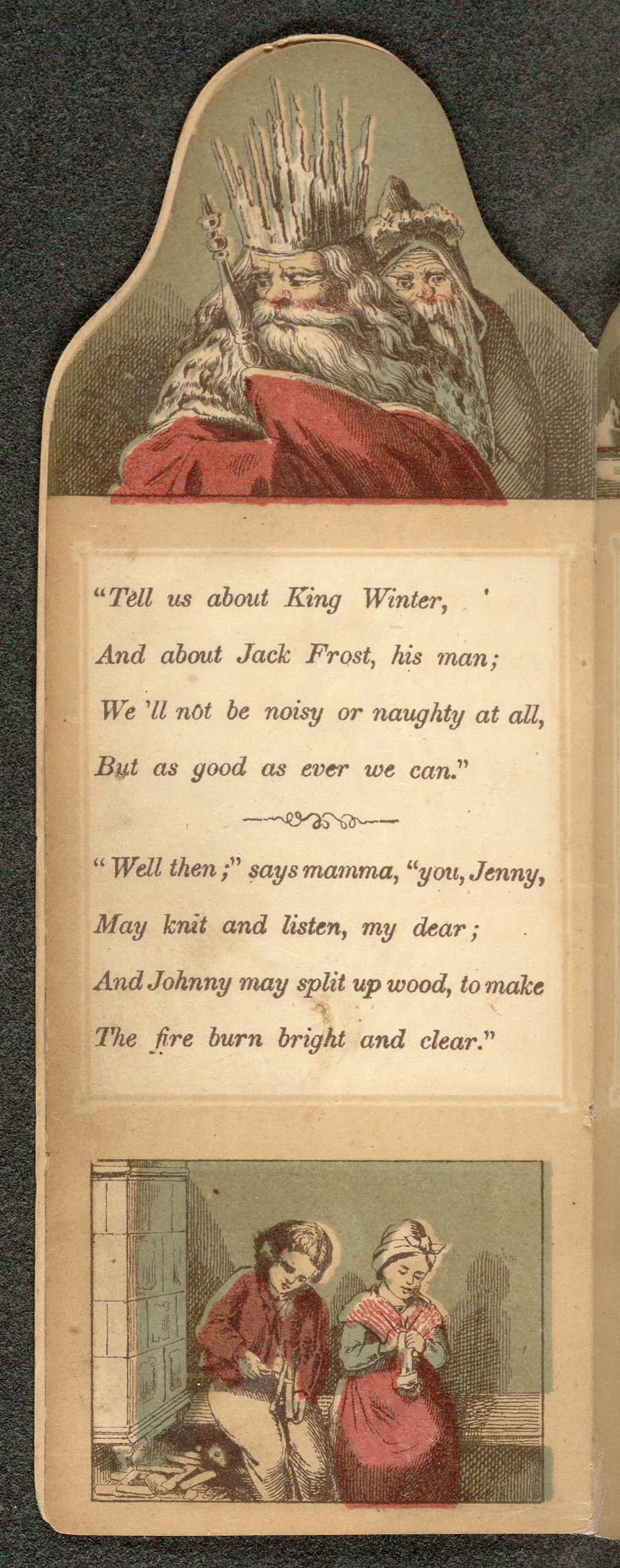

But who knows, King Winter—an 1859 tale in verse of a proto-Santa Claus figure, in a book partially shaped like the outline of the title character’s head—might still captivate. As might many other titles of note.

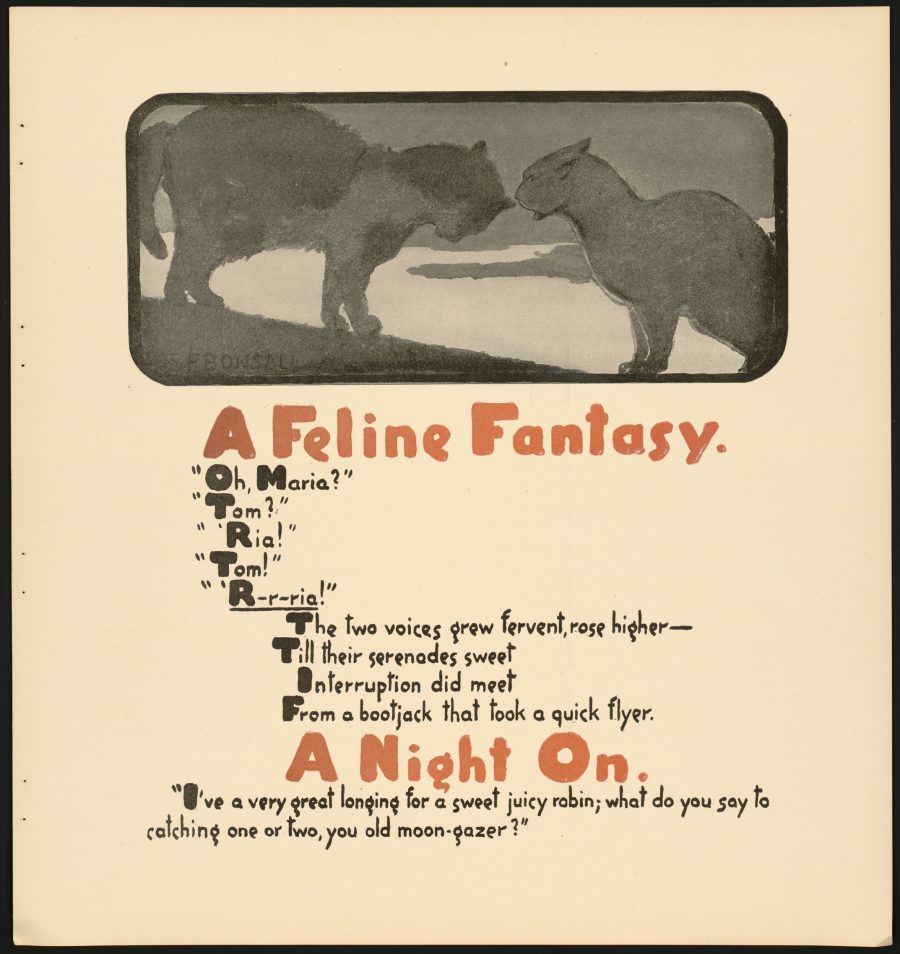

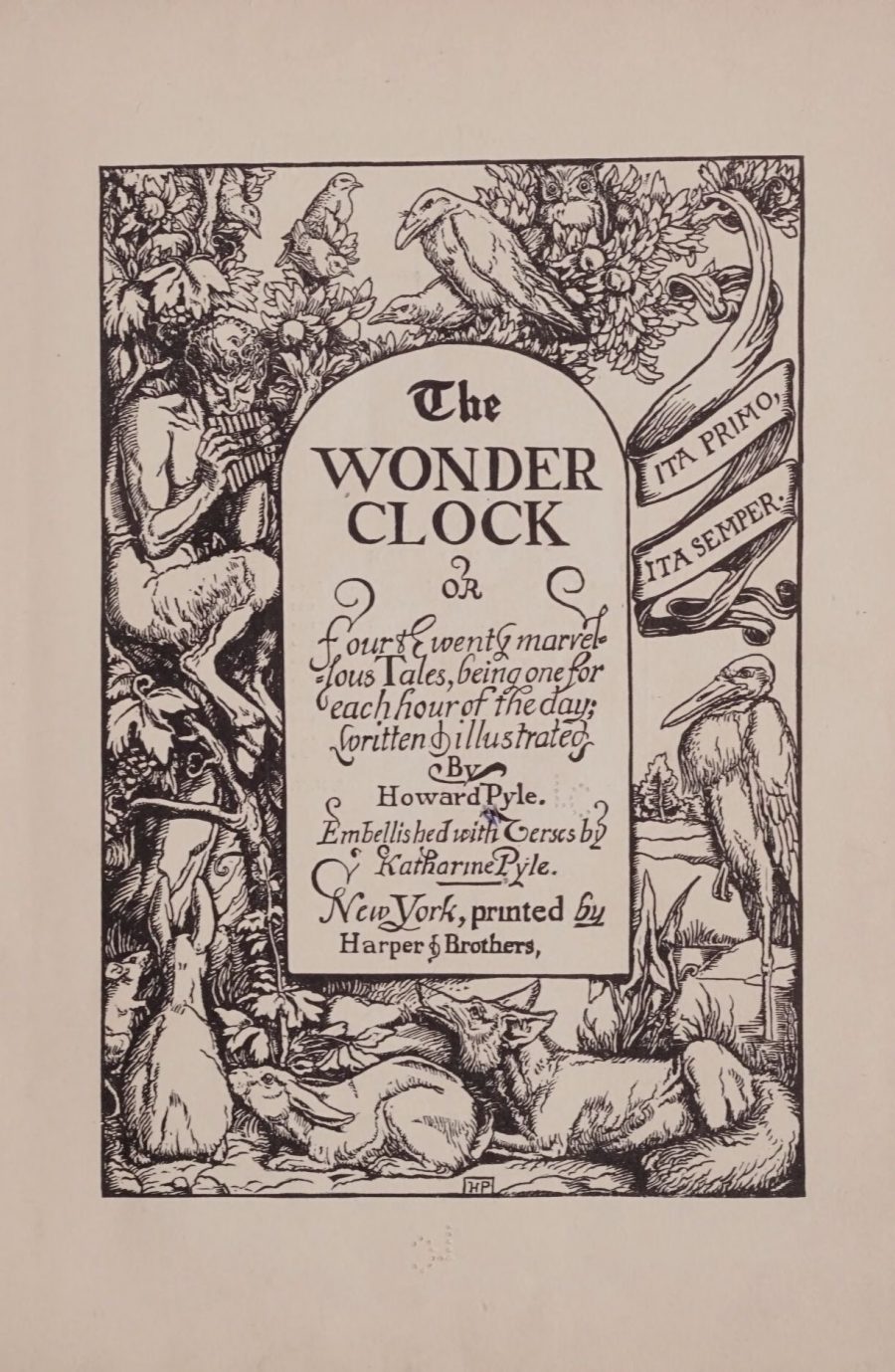

A sly collection of stories from 1903 called The Book of the Cat, with “facsimiles of drawings in colour by Elisabeth F. Bonsall”; a book of “Four & twenty marvellous tales” called The Wonder Clock, written and illustrated by Howard Pyle in 1888; and Edith Francis Foster’s 1902 Jimmy Crow about a boy named Jack and his boy-sized crow Jimmy (who could deliver messages to other young fancy lads).

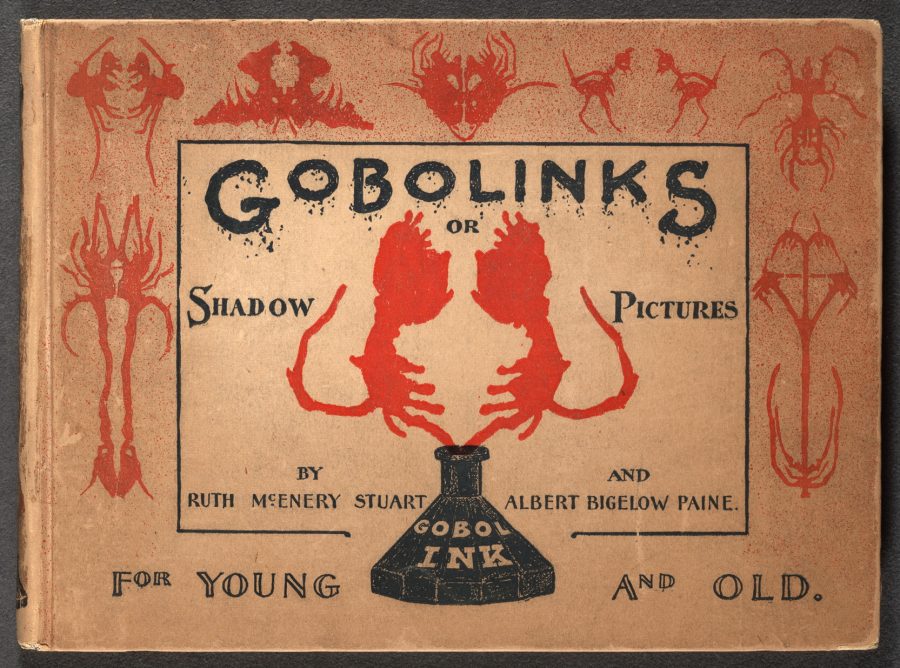

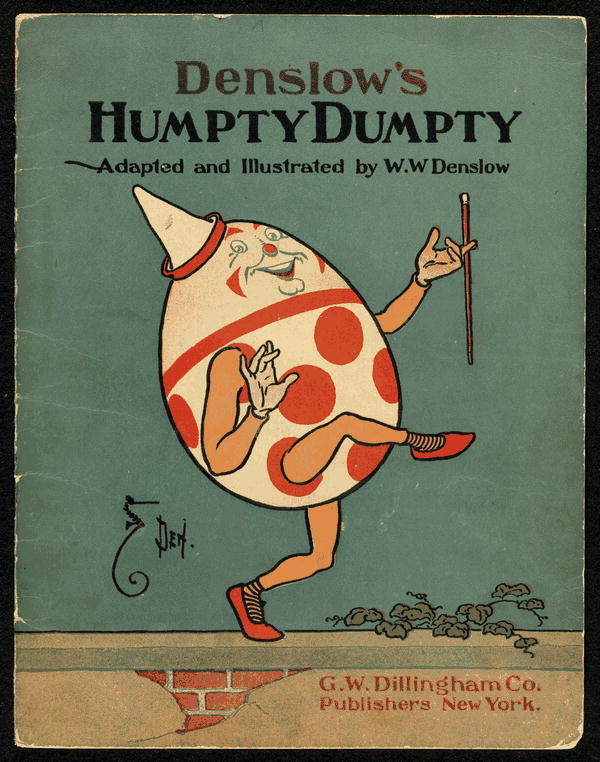

An 1896 book called Gobolinks introduces a popular inkblot game of the same name that predates Hermann Rorschach’s tests by a couple decades. Other highlights include “examples of the work of American illustrators such as W.W. Denslow, Peter Newell… Walter Crane and Kate Greenaway,” writes the Library on its blog. The digitized collection debuted to mark the 100th anniversary of Children’s Book Week, celebrated during the last week of April in all 50 states in the U.S.

“It is remarkable,” says Lee Ann Potter, director of the LoC’s Learning and Innovation Office, “that when the first Children’s Book Week was celebrated, all of the books in the online collection… already existed.” Now they exist online, not only because of the technology to scan, upload, and share them, but “because careful stewards insured that these books have survived.”

Digital versions of today’s kids books could mean that there is no need to carefully preserve paper copies for posterity. But we can be grateful that archivists and librarians of the past saw fit to do so for this fascinating collection of children’s literature. The theme of this year’s Children’s Book Week—Read Now, Read Forever—“looks to the past, present, and most important, the future of children’s books.” Enter the Library of Congress digital collection of children’s books from over a century ago (and see the other sizable online archives at the links below) to visit their past, and imagine how vastly different their future might be.

Related Content:

A Digital Archive of 1,800+ Children’s Books from UCLA

Hayao Miyazaki Picks His 50 Favorite Children’s Books

Enter an Archive of 6,000 Historical Children’s Books, All Digitized and Free to Read Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply