Stories of idiosyncratic and demanding composers and bandleaders abound in mid-century jazz—of pioneers who pushed their musicians to new heights and in entirely new directions through seeming sheer force of will. Miles Davis’ name inevitably comes up in such discussions. Davis was “not a patient man,” jazz historian Dan Morgenstern remarks, “and I think he got impatient with himself just as he did with other people.” Jazz and other forms of music have been immeasurably enriched by that impatience.

Other bop eccentrics—like John Coltrane—brought their own personality quirks and personal struggles to bear on their styles, pushing toward new insights and experiments that shaped the future of the music. Their peer Thelonious Monk, writes Candace Allen at The Guardian, “the jobbing musician who couldn’t, more than wouldn’t, conform to the conventions of the job,” seemed the odd man out. He “spent most of his professional life struggling to support his family.” Monk’s “misdiagnosed and ignorantly medicated bipolar condition” and his stubborn refusal to follow trends made it difficult for him to achieve the success he deserved.

But it was Monk’s inability to do things any way but his way that made up the essence of his greatness—his insistence on “playing angular, spacious and ‘slow,’” his “daunting and mysterious” silences. A musical prodigy, Monk honed his piano chops in Baptist churches and New York rent parties before his residency as house pianist for Teddy Hill’s band at the famed Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem, where he helped usher in the “bebop revolution.” While he “charted a new course for modern music few were willing to follow,” notes All About Jazz, those who did learned a new way of playing, Monk’s way.

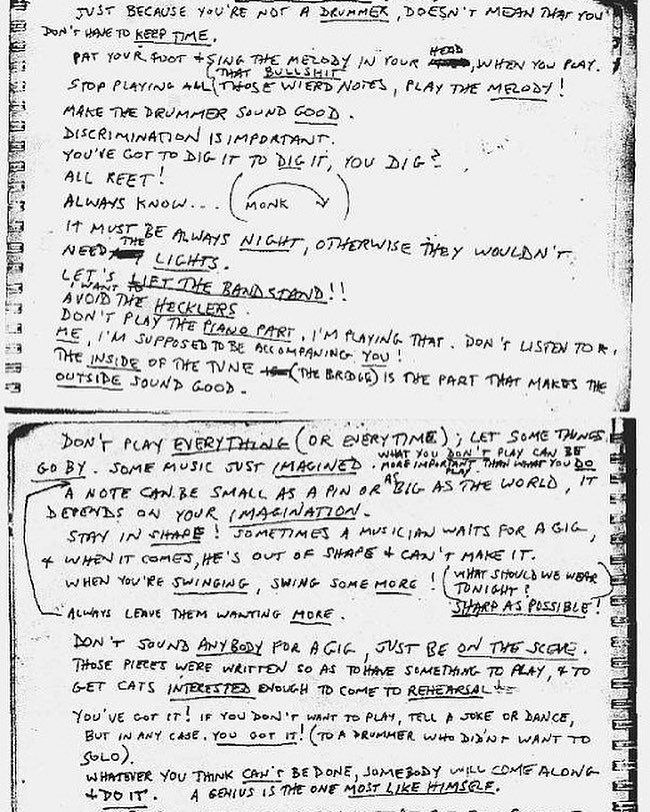

What does that mean? The list above, as transcribed by saxophonist Steve Lacy, lays it all out. “T. Monk’s Advice,” as it’s called, offers guidelines, pointers, and pointed commands. Some of these instructions relate directly to live performance (“don’t sound anybody for a gig, just be on the scene,” “avoid the hecklers”). Others get at the heart of Monk’s genius—his talent for creating space, both inside the arrangements and between the notes. Monk makes sure he’s the only one playing “weird notes,” demanding that musicians “play the melody!” “Don’t play the piano part,” he says, “I am playing that.” And he peppers the list with cryptic philosophical and social observations (“discrimination is important,” “always know,” “a genius is the one most like himself”).

In the last item on the list (cut off in the image above), Monk veers sharply away from music with some humorous social commentary. It’s a move that’s typical Monk—both deeply serious and playful, entirely unexpected, and leaving us, as he instructs his musicians, “wanting more.” See a transcription of Monk’s list of advice for musicians below.

Just because you’re not a drummer, doesn’t mean that you don’t have to keep time.

Pat your foot and sing the melody in your head when you play.

Stop playing all that bullshit, those weird notes, play the melody!

Make the drummer sound good.

Discrimination is important.

You’ve got to dig it to dig it, you dig?

All reet!

Always know

It must be always night, otherwise they wouldn’t need the lights.

Let’s lift the band stand!!

I want to avoid the hecklers.

Don’t play the piano part, I am playing that. Don’t listen to me, I am supposed to be accompanying you!

The inside of the tune (the bridge) is the part that makes the outside sound good.

Don’t play everything (or everytime); let some things go by. Some music just imagined.

What you don’t play can be more important than what you do play.

A note can be small as a pin or as big as the world, it depends on your imagination.

Stay in shape! Sometimes a musician waits for a gig & when it comes, he’s out of shape & can’t make it.

When you are swinging, swing some more!

(What should we wear tonight?) Sharp as possible!

Always leave them wanting more.

Don’t sound anybody for a gig, just be on the scene.

Those pieces were written so as to have something to play & to get cats interested enough to come to rehearsal!

You’ve got it! If you don’t want to play, tell a joke or dance, but in any case, you got it! (to a drummer who didn’t want to solo).

Whatever you think can’t be done, somebody will come along & do it. A genius is the one most like himself.

They tried to get me to hate white people, but someone would always come along & spoil it.

via Lists of Note

Related Content:

Captain Beefheart Issues His “Ten Commandments of Guitar Playing”

John Coltrane’s Handwritten Outline for His Masterpiece A Love Supreme (1964)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Words to live by even for us non-musicians.