In December 1931, having just embarked on a 40-stop lecture tour of the United States, Winston Churchill was running late to dine with financier Bernard Baruch on New York City’s Upper East Side. He hadn’t bothered to bring Baruch’s address, operating under the incorrect assumption that his friend was so distinguished a personage, any random cab-driving commoner would automatically recognize his building.

Such were the days before cell phones and Google Maps.…

Eventually, Churchill bagged the cab, and shot out across 5th Avenue mid-block, thinking he would fare better on foot.

Instead, he was very nearly “squashed like a gooseberry” when he was struck by a car traveling about 35 miles an hour.

Churchill, who wasted no time peddling his memories of the accident and subsequent hospitalization to The Daily Mail, explained his miscalculation thusly:

In England we frequently cross roads along which fast traffic is moving in both directions. I did not think the task I set myself now either difficult or rash. But at this moment habit played me a deadly trick. I no sooner got out of the cab somewhere about the middle of the road and told the driver to wait than I instinctively turned my eyes to the left. About 200 yards away were the yellow headlights of an approaching car. I thought I had just time to cross the road before it arrived; and I started to do so in the prepossession—wholly unwarranted— that my only dangers were from the left.

Yeah, well, that’s why we paint the word “LOOK” in the crosswalk, pal, equipping the Os with left-leaning pupils for good measure.

Another cab ferried the wounded Churchill to Lenox Hill Hospital, where he identified himself as “Winston Churchill, a British Statesman” and was treated for a deep gash to the head, a fractured nose, fractured ribs, and severe shock.

“I do not wish to be hurt any more. Give me chloroform or something,” he directed, while waiting for the anesthetist.

After two weeks in the hospital, where he managed to develop pleurisy in addition to his injuries, Churchill and his family repaired to the Bahamas for some R&R.

It didn’t take long to feel the financial pinch of all those cancelled lecture dates, however. Six weeks after the accident, he resumed an abbreviated but still grueling 14-stop version of the tour, despite his fears that he would prove unfit.

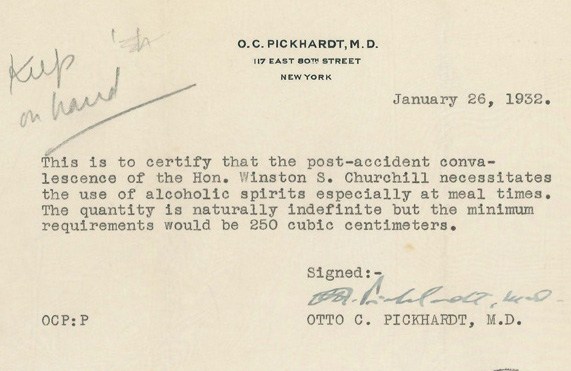

Otto Pickhardt, Lenox Hill’s admitting physician came to the rescue by issuing Churchill the Get Out of Prohibition Free Pass, above. To wit:

…the post-accident convalescence of the Hon. Winston S. Churchill necessitates the use of alcoholic spirits especially at meal times. The quantity is naturally indefinite but the minimum requirements would be 250 cubic centimeters.

Perhaps this is what the eminent British Statesman meant by chloroform “or something”? No doubt he was relieved about those indefinite quantities. Cheers.

Read Churchill’s “My New York Misadventure” in its entirety here. You can also learn more by perusing this section of Martin Gilbert’s biography, Winston Churchill: The Wilderness Years.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2016.

Related Content:

What Happens When Mortals Try to Drink Winston Churchill’s Daily Intake of Alcohol

Oh My God! Winston Churchill Received the First Ever Letter Containing “O.M.G.” (1917)

Winston Churchill Goes Backward Down a Water Slide & Loses His Trunks (1934)

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. She lives in New York City, some 30 blocks to the north of the scene of Churchill’s accident. Follow her @AyunHalliday

Priceless tidbit…cheers!

Crazy stuff…funky though

Minimum is 250cc, which is 250ml, or one-third of a standard bottle of whisky, gin, etc. Phew!

Almost exactly one cup.

“Yeah, well, that’s why we paint the word “LOOK” in the crosswalk, pal, equipping the Os with left-leaning pupils for good measure.”

That remark is rather intolerant. Churchill by instinct looked the wrong way because we drive on the left in the UK (and in most of the then British Empire); the USA drives on the right, no doubt because of contrariness or French influence at the time of the war of independence.