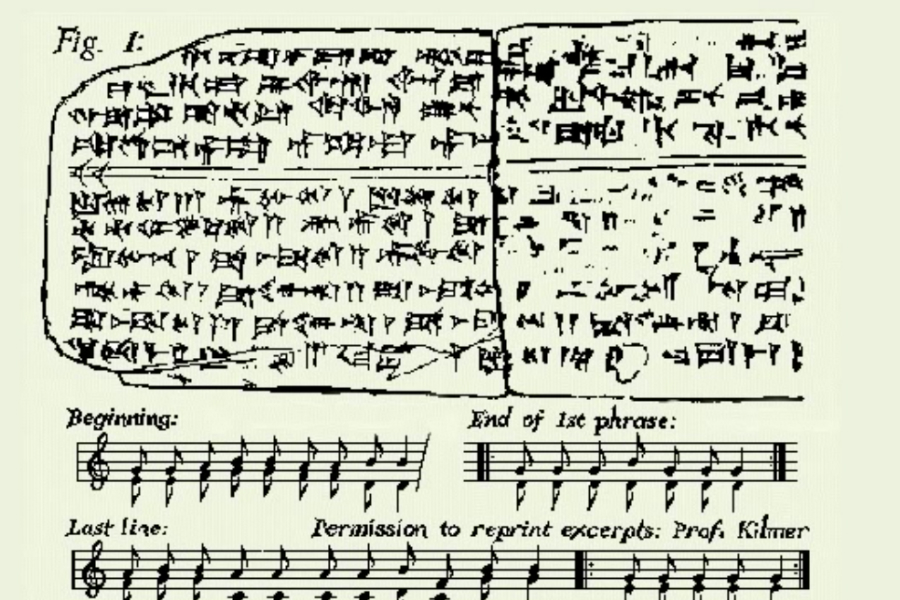

In the early 1950s, archaeologists unearthed several clay tablets from the 14th century BCE. Found, WFMU tells us, “in the ancient Syrian city of Ugarit,” these tablets “contained cuneiform signs in the hurrian language,” which turned out to be the oldest known piece of music ever discovered, a 3,400 year-old cult hymn. Anne Draffkorn Kilmer, professor of Assyriology at the University of California, produced the interpretation below in 1972. (She describes how she arrived at the musical notation—in some technical detail—in this interview.) Since her initial publications in the 60s on the ancient Sumerian tablets and the musical theory found within, other scholars of the ancient world have published their own versions.

The piece, writes Richard Fink in a 1988 Archeologia Musicalis article, confirms a theory that “the 7‑note diatonic scale as well as harmony existed 3,400 years ago.” This, Fink tells us, “flies in the face of most musicologists’ views that ancient harmony was virtually non-existent (or even impossible) and the scale only about as old as the Ancient Greeks.”

Kilmer’s colleague Richard Crocker claimed that the discovery “revolutionized the whole concept of the origin of western music.” So, academic debates aside, what does the oldest song in the world sound like? Listen to a midi version below and hear it for yourself. Doubtless, the midi keyboard was not the Sumerians instrument of choice, but it suffices to give us a sense of this strange composition, though the rhythm of the piece is only a guess.

Kilmer and Crocker published an audio book on vinyl (now on CD) called Sounds From Silence in which they narrate information about ancient Near Eastern music, and, in an accompanying booklet, present photographs and translations of the tablets from which the song above comes. They also give listeners an interpretation of the song, titled “A Hurrian Cult Song from Ancient Ugarit,” performed on a lyre, an instrument likely much closer to what the song’s first audiences heard. Unfortunately, for that version, you’ll have to make a purchase, but you can hear a different lyre interpretation of the song by Michael Levy below, as transcribed by its original discoverer Dr. Richard Dumbrill.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2014. It’s old but gold. So we hope you enjoy revisiting it again.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

What Ancient Greek Music Sounded Like: Hear a Reconstruction That is ‘100% Accurate’

Hear The Epic of Gilgamesh Read in the Original Akkadian and Enjoy the Sounds of Mesopotamia

I enjoyed the article but wonder what language other than akkadian, such as sumerian might have preserved remnants of it.I realize the assyrian king whose name I don’t recall preserved the products of earlier cultures but are there more tablets with that same hymn.

Hello,

I have heard for years that Sumerian language could not be deciphered. I read it is all cuneiform. Does this represent a breakthrough?

Or, it’s translation simply a part here and there and will be a struggle with interspersed successes?

Thank you,

Billy

I wonder how they realized it was musical notation, and how they deciphered it was a diatonic scale in more detail. Im a musician and im intrigued by this topic.

I don’t never understand most of these stories without pictures. Any?

If the song is 3,400 years then it couldn’t be Sumerian because they were already extinct by then. Maybe Egyptian is more like it.

watch Paul Cooper’s fall as civilization podcast on the ancient Assyrians and Sumerians. The Assyrians is episode empire of iron and I believe the Sumerians is episode 1. they read poetry and even a note from a 7‑year-old boy that was away at school that was written on a clay tablet. I think you would find it interesting.