Image via Hereford Cathedral and Hereford Mappa Mundi Trust

At this point, every aspect of William Shakespeare’s life has produced more speculation than any of us could digest in a lifetime. That goes for his professional life, of course, but also his even more scantily documented personal life. As far as his marriage is concerned, the known facts are these: on November 27th, 1582 a marriage license was issued in Worcester to the 18-year-old William Shakespeare and the approximately 26-year-old Anne Hathaway. Six months later came the first of their three children, Susanna. For most of his professional life, William lived in London, while Anne — willed only her husband’s “second-best bed” — remained in his hometown of Stratford-upon-Avon.

According to one common interpretation, the Shakespeares’ was a shotgun wedding avant la lettre, motivated less by romance than expediency. That would certainly explain their apparent choice to live apart, though William’s career would probably have brought him to London anyway, and without a good reason to be in the city, it wasn’t a bad idea to keep the kids out of plague range. (As for his best bed, it would customarily have been reserved for guests.) But according to a new interpretation of an old document by the University of Bristol professor Matthew Steggle, the couple could not only have remained in communication, but also lived together in the capital for a time.

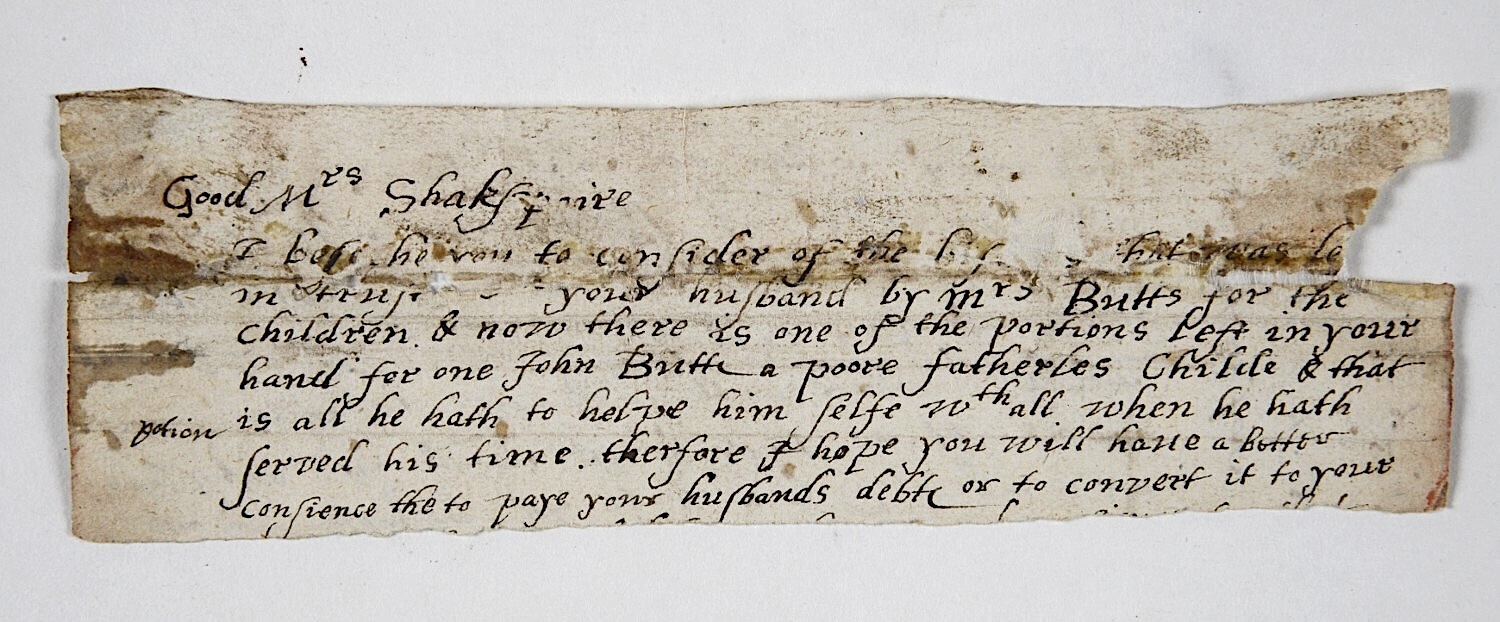

“Hereford Cathedral Library holds a fragmentary seventeenth-century letter addressed to a ‘Mrs Shakspaire,’ concerning her husband’s dealings with a fatherless apprentice,” writes Steggle in his research paper recently published in the journal Shakespeare. “Of the Shakespeares recorded in London, William Shakespeare is the only viable candidate to fit with the letter’s details.” In Steggle’s analysis, it “paints a picture of William and Anne Shakespeare together in London, and living, perhaps around 1599–1603, in Trinity Lane. It further suggests an Anne Shakespeare who is not absent from her husband’s London life, but present and engaged in his financial and social networks.”

The New York Times’ Ephrat Livni quotes Steggle as saying that “this letter, if it belongs to them, offers a glimpse of the Shakespeares together in London, both involved in social networks and business matters, and, on the occasion of this request, presenting a united front against importunate requests to help poor orphans.” This, Livni adds, would “lend some heft to feminist readings of Shakespeare’s life,” as well as to the pop-culture trend of “rethinking the marriage and Hathaway’s role in it.” Each era thus continues to create the Shakespeare for whom it feels the need — and the Mrs. Shakespeare as well.

Related content:

Free Course: A Survey of Shakespeare’s Plays

Why Should We Read William Shakespeare? Four Animated Videos Make the Case

The Only Surviving Script Written by Shakespeare Is Now Online

Did Shakespeare Write Pulp Fiction? (No, But If He Did, It’d Sound Like This)

Did Bach’s Wife Compose Some of “His” Masterpieces? A New Documentary Says Yes

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.